Debt Monetization in Asia Given Nod by IMF in Policy Shift

IMF’s Nod to Asian Debt Monetization Marks Shift in Orthodoxy

(Bloomberg) -- The International Monetary Fund’s October acknowledgment of the case for temporary debt monetization in Asia marked yet another example of how the pandemic has upended economic orthodoxy.

It’s an about face for the IMF in a region where its calls for policy austerity are sometimes blamed for worsening the economic hardship caused by the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s.

In 1998, as a financial crisis raged across Asia, then-IMF Managing Director Michel Camdessus was photographed as he stood with arms folded watching Indonesian President Suharto sign an unpopular bailout agreement that demanded steep spending cuts and painful reforms.

Now, the IMF is at the other end of the policy spectrum by acknowledging in its outlook for the region that those countries with limited room to borrow, or who are vulnerable to swings in bond market sentiment as deficits soar, can lean more on their central banks. The October report even gave qualified approval for central banks in some cases to directly buy their government’s debt, with a list of conditions.

“These are highly unusual and exceptional times,” Jonathan D. Ostry, acting director of the IMF’s Asia and Pacific Department said in an email response to follow up questions from Bloomberg News.

“In such highly exceptional circumstances, in cases where inflation remains low, debt monetization could be appropriate, provided it is well communicated, time-bound, and implemented within a clear operational framework that preserves central bank independence and does not impede monetary policy,” he said.

Indonesia’s debt monetization program approved in July and implemented in August has earned worldwide attention. Bank Indonesia has snapped up more than 270 trillion rupiah ($20 billion) in government bonds so far, while reiterating alongside a surprise interest rate cut last week that it won’t carry direct purchases into 2021.

Central bank and finance officials have calmed investors around the “burden-sharing” arrangement, repeating a pledge to keep it temporary. They’ve also worked to quell worries around proposed legislation that was initially seen to threaten central bank independence. The rupiah is the biggest gainer in the Asia currency basket in the past month, rising more than 3% against the greenback.

In the Philippines, where talk of direct purchases was bubbling up as the economy suffered from a resurgence of the virus, the central bank has recently scaled back debt purchases. While officials at Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas have said they remain ready to use unconventional policies as needed, their purchases of securities even in the secondary market has fallen in data through October.

Measures taken by governments in the years since the Asia crisis, such as bolstering foreign exchange reserves, mean the region’s governments have more wiggle room this time compared to the 1990s crisis, said Brad Setser, senior fellow on leave from the Council on Foreign Relations and a former economist at the U.S. Treasury Department, who commented before being named to president-elect Joe Biden’s transition team.

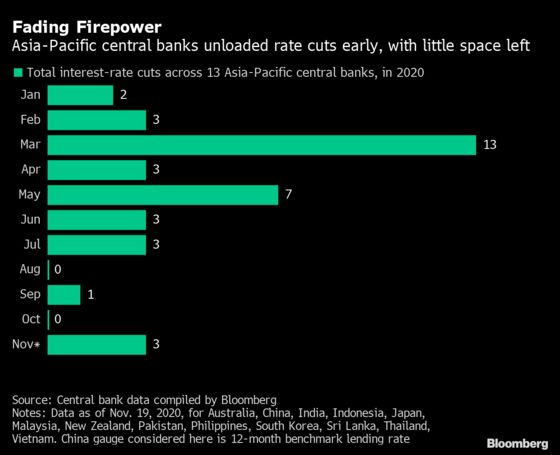

“The constraints that Asia faced in 1997 simply aren’t there,” he said, adding that asset purchases -- given interest rates have been slashed -- are now an accepted part of the monetary policy toolkit globally.

“It would be very strange for the IMF to recognize needs for asset purchases to address constraints of zero lower bound in advanced economies and not recognize that some emerging economies are in a similar position,” Setser said.

Thailand and South Korea are two such Asian economies approaching the zero lower bound, each showing a benchmark interest rate of 0.5% after 75 basis points in cuts this year.

Mark Sobel, a former U.S. representative at the IMF who’s now at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum think tank, said it’s a sign of the macroeconomic policy space these countries now have that they can lean on policies such as asset purchases without spooking investors.

“It was made possible by the progress they’ve made in strengthening their economic fundamentals in recent decades since the Asia crisis,” Sobel said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.