If Merkel Wants to Fix Germany’s Economy, She Needs to Hurry

If Merkel Wants to Fix the German Economy, She Needs to Hurry Up

(Bloomberg) --

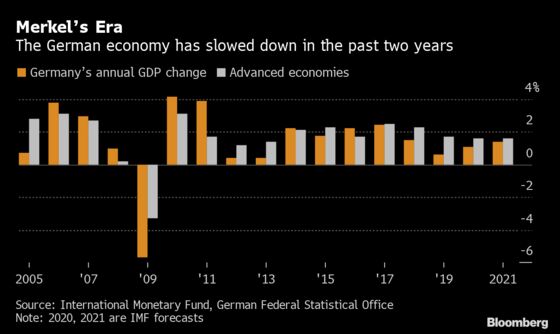

Angela Merkel is running out of time to reset the German economy before her era as chancellor draws to a close.

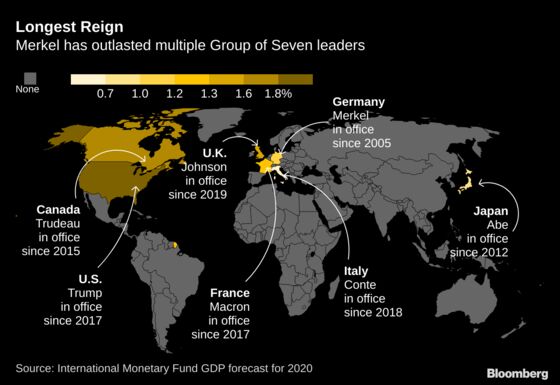

The Group of Seven’s longest-serving leader weathered the financial crisis and Europe’s debt turmoil. But in the final full year of her tenure, as Germany’s economic problems fester, lawmakers are starting to ask if she has the vision and energy to fix them.

At stake is whether the dominant growth engine of 21st century Europe can sustain the continent’s relevance in a world overshadowed by intensifying rivalry between the U.S. and China. Germany’s ability to do that looks vulnerable, as the formula that drove its postwar success falters.

The powerful German carmakers missed the speed and force with which their industry would embrace the shift to electric vehicles, and are scrambling to catch up. Meanwhile U.S. President Donald Trump’s attacks on the global trading order are threatening Germany’s export-based model.

The country Merkel leads boasts a record budget surplus and has enjoyed uninterrupted growth for almost a decade, but in 2019 it flirted with recession and posted its slowest expansion in half a decade. Unless she can stop the rot, the chancellor risks bequeathing to her successor an economy whose best days could be behind it.

In theory, Merkel still has about 18 months to govern before the summer holidays of 2021 mark the beginning of the next election campaign and the end of any real policy making. To take advantage of that, she’ll need to get past a coalition partner, the SPD, which feels like it has too often paid the price for helping her out.

The countdown to her exit is already focusing minds in her CDU party. The chief of that group, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, told Bloomberg Television in Davos in Thursday that she plans to assemble her team to succeed Merkel by the end of this year.

In the meantime, the chancellor herself appears more focused on foreign policy challenges on Europe’s doorstep, such as the war in Libya and the unraveling Iran nuclear accord. She will probably emphasize such themes when she speaks at the World Economic Forum on Thursday.

When Merkel met her CDU lawmakers last week, she addressed those geopolitical matters while ignoring calls from some for business-friendly tax measures, according to people present.

For her citizens, growth prospects are more concerning however. In a global survey of 26 countries by Edelman, the country scored third-lowest in a measure of sentiment, with only 23% of respondents optimistic for the economy’s future.

“We can’t afford to stay idle,” said Eckhardt Rehberg, the budget leader of Merkel’s CDU/CSU party grouping in Parliament. “We have no time to lose to put Germany on the right track for the future.”

Germany took first place this year in the Bloomberg Innovation Index, with good scores on value-added manufacturing, high-tech density, and patent activity. But a lot of the expertise is concentrated in the auto sector, which is already starting to show the wear and tear of the shifts away from diesel, and toward electric and self-driving cars.

Other pillars of industry are also confronting how to adapt to a region-wide shift toward more climate friendly policies, while the country as a whole has struggled to keep pace with digital developments.

Auto Ailments

Cars remain the most pressing source of concern, with PSA Group’s German carmaking division Opel and auto parts maker Continental already retrenching. The advent of electric engines could threaten as many as half of the industry’s 834,000 workers by the end of the decade, according to a government-sponsored working group.

Merkel’s current response to that challenge draws from her 2008 crisis playbook, offering wage subsidies for companies to prevent job losses. But the industry faces geopolitical challenges as well as technological ones.

Tariffs against auto producers is the nuclear option that Trump raises when he wants to really focus the minds of the European Union on his concerns. This month, U.S. officials even raised the prospect as they tried to muscle the bloc into line on Iran.

The deeper fear in Berlin is that the U.S. president, having clinched an initial trade deal with China, will shift focus to Europe -- with Germany in his sights. He suggested as much in Davos this week. Even while Trump holds off on car tariffs, the U.S. is forcing the issue with Huawei, the Chinese telecom equipment maker.

The U.S. is demanding that Germany bans Huawei from its next generation of communication networks on security grounds. China -- Germany’s biggest trading partner -- is ready to retaliate. Merkel who sees the advantage in building new allies and who would need Huawei technology to modernize the country’s creaking mobile system, is caught in the middle.

So far the government has put in place restrictions that will allow officials to keep Huawei out of critical infrastructure without imposing an official ban. But Merkel faces a rebellion from CDU lawmakers who want tougher restrictions, even if it means a backlash from China.

What Bloomberg’s Economists say

“The era of unbridled globalization is over. World trade growth slowed following the global financial crisis and U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade war with China has challenged the old order of free trade. Germany can no longer depend on overseas trade to drive up prosperity in the same way as it did.”

-Jamie Rush. See his GERMANY INSIGHT

It’s all a far cry from 2005, when Merkel appeared in Davos on the cusp of the electoral success that would propel her to 14 years as chancellor. Back then -- when Germany was still known as the sick man of Europe -- she pledged a 100-day program of measures from cuts in labor costs to lower corporate taxes.

Those are the sort of growth-friendly policies that Friedrich Merz, a CDU challenger for Merkel’s succession, is seeking 15 years later. But the chancellor, whose last move to lower corporate taxes was in 2008, is more inclined to point to the country’s budget surplus as a sign of her fiscal discipline than to use it to upgrade the economy for the challenges ahead.

In the twilight of her administration, Merkel seems more concerned with firefighting abroad than wrestling with her coalition over the economy. Some lawmakers fret that her economic policy amounts to little more than managing Germany’s decline.

“We’ve rested a bit on the laurels of our export success,” said Karsten Junius, chief economist at Bank J. Safra Sarasin. “We’re much too neglectful, much too ready to accept mediocrity.”

--With assistance from Catherine Bosley, Arne Delfs and Alaa Shahine.

To contact the reporters on this story: Birgit Jennen in Berlin at bjennen1@bloomberg.net;Craig Stirling in Frankfurt at cstirling1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Ben Sills at bsills@bloomberg.net, ;Simon Kennedy at skennedy4@bloomberg.net, Zoe Schneeweiss

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.