How Fed Can Make a Better Dot Plot After December's Misfire

U.S. stocks plunged 3.5 percent in just over an hour after Fed’s dot-plot projection.

(Bloomberg) -- How do you talk about your best guess for where the economy is headed while also highlighting your worst fears?

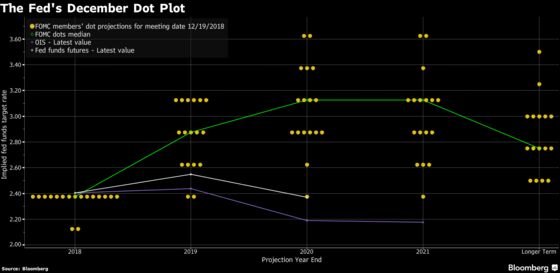

That question is proving a major challenge for Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues in the wake of December’s communications misfire. When the Fed’s so-called dot plot of the projected interest-rate path signaled two hikes for 2019, U.S. stocks plunged 3.5 percent in just over an hour.

In retrospect, investors got only part of the message that should have emerged. They heard loud and clear the baseline forecast for two rate hikes, but not that policy makers’ confidence in that forecast was significantly weakening, as minutes later showed. Just six weeks later the Fed effectively scrapped those projections in signaling it would keep rates on hold for some time.

Loretta Mester, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, said the central bank’s approach to communication was undergoing a year of transition and the uncertainty bands around its quarterly projections, including the dot plot, “deserve more attention.”

“The fact that the dots can change over time because of economic developments is a design feature, not a flaw,” she told an audience Tuesday in Newark, Delaware.

The Fed would like to avoid that outcome again. There’s no easy fix, though, in their potential options for systematically conveying forecast certainty. Powell has entrusted Vice Chairman Richard Clarida to come up with a solution, and the central bank has tested some tools privately before.

“The problem with the dot plot is that it shows the quarterly rate forecasts but doesn’t communicate anything about the likelihood of that path,’’ said Andrew Levin, a Dartmouth College professor who previously advised the Fed Board on monetary policy strategy and communications.

Without a reliable mechanism for communicating forecast certainty, or uncertainty, the burden will fall more on Powell to work that message into his press conferences and get it just right.

Here’s a rundown of some possibilities discussed by former Fed officials and advisers:

More Forecasts

Now that Powell is holding press conferences eight times a year, instead of four, he could ask the Federal Open Market Committee to provide forecasts at every meeting.

A changing forecast every six weeks would show more agility in response to recent data, giving a sense of how officials’ views are evolving. Still, that wouldn’t communicate how they would respond to unforeseen outcomes further down the road, or how much weight they put on the probability of those outcomes.

Such a change probably wouldn’t alter the thrust of Fed communications which is focused on rationales for why they did what they did, rather than what they might do.

Different Scenarios

William English, an economist at Yale University who also served as a senior adviser to officials on communication, said it might be helpful if officials explained how policy should adjust to hypothetical scenarios that fall outside their baseline forecasts, and present those alongside their quarterly outlooks.

“It seems to me the public often wants to hear not just about the modal outlook, but what it would take for the committee to do something different,” he said.

The idea is intriguing because it would quantify how the Fed would react to, say, a weakening expansion or surging inflation. It also carries risks, such as the chance that mentioning a downside scenario -- such as a continuous plunge in stocks -- could spook investors.

“I don’t think they would want to feed that beast,” said Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co. in New York.

It might also create more confusion than clarity. The Fed experimented with the idea in 2012, asking all 17 policy makers to provide a policy path responding to four alternate forecast scenarios -- a “maze of 68 possibilities,” as St. Louis Fed President James Bullard put it at the time.

“I don’t think that kind of information overload is very conducive to improving transparency,” Bullard said in an FOMC meeting transcript.

Consensus Forecasts

Overcoming such divergence -- through consensus forecasts -- would require a giant leap toward agreement among all governors and regional Fed presidents on how rates should respond in each scenario.

Right now, officials don’t even have a single forecast for their baseline outlook. The projections are a compilation of each individual’s outlook based on “optimal” monetary policy. The median estimate is simply the midpoint and doesn’t represent something the committee, as a group, agrees on.

The Fed also explored the idea of a consensus baseline forecast in 2012.

“In the end, people thought it just wasn’t going to be that helpful, in part because there would be people standing outside the consensus.” said English, a top staff official at the time.

Formulaic Approach

Another option could be to publish scenarios with policy paths based on a model -- essentially, a set of economic formulas. Fed officials would still have to agree that the interest-rate rule within the model was in line with theirs, again a difficult challenge given the diversity of views on the committee.

--With assistance from Jeanna Smialek and Rich Miller.

To contact the reporters on this story: Craig Torres in Washington at ctorres3@bloomberg.net;Christopher Condon in Washington at ccondon4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Scott Lanman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.