Central Banks Are Fast Running Out of Room for Further Rate Cuts

The findings suggest monetary policy can still be loosened before being fully exhausted.

(Bloomberg) --

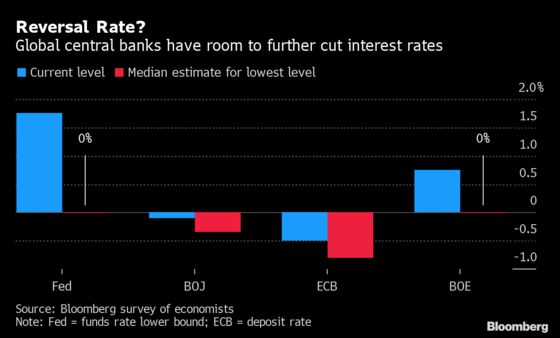

Global central banks have room to further cut interest rates before they begin to do more harm than good, although the Federal Reserve is unlikely to push its benchmark below zero, according to a survey of economists.

With the slumping world economy already forcing the Fed and European Central Bank to lower borrowing costs, policy makers are primed to do more. Yet they are also aware that at some point they will have to stop using that tool as stimulus for fear of hitting the so-called reversal rate, at which cheap money turns contractionary.

The new Bloomberg survey of economists suggests the Fed and Bank of England, both of whom have signaled opposition to negative rates, would only reduce their benchmarks to zero from a range of 1.75% to 2% and 0.75% respectively now.

By contrast, the ECB should be able to drop its deposit rate to as low as minus 0.8% from the current minus 0.5%, and the Bank of Japan could lower its key rate to minus 0.35% from minus 0.1%, according to the poll’s median estimates.

The findings suggest monetary policy can still be loosened before being fully exhausted, which is welcome news in a world economy beset by trade tensions and where manufacturing is already in recession. They nevertheless also signal central banks have less firepower than historically -- which may alarm investors and underscore calls for governments to do more if the current slowdown endures.

“Currently, it seems that the ECB and Bank of Japan have the will to press interest rates lower in the event of an economic downturn,” said Timo Hirvonen, chief economist at FIM Group OYJ in Helsinki. “The Fed and Bank of England do not see negative interest rates as an option.”

Markus Brunnermeier and Yann Koby of Princeton University popularized the idea of a reversal rate in a study which argued that at some point, accommodative monetary policy turns contractionary because banks cease lending amid concerns about their equity positions or the need to satisfy capital regulations. Some banks, especially those in Europe, have begun arguing against negative rates.

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say...“All of the debate, uncertainty, and complexity around the lower bound for rates obscures a simple truth -- somewhere not too far from zero, the cost of cuts starts to outweigh the benefits. Some major central banks are already there. If the next downturn comes sooner than we think, others won’t be far behind.”

-- Tom Orlik

Another reason to suspect there’s a floor for rates is the suspicion that the lower benchmarks go, the more people will raise savings in order to protect their retirement. Some policy makers have also argued there’s the risk that rock-bottom rates will inflate asset bubbles or damage productivity.

“Negative rates have diminishing marginal returns in terms of expectations for inflation and incentivizing investment and spending,” said Constance Hunter, chief economist at KPMG LLP.

The Fed has already cut its benchmark twice this year, with policy makers led by Chairman Jerome Powell leaning towards acting again. But Powell said last month that negative rates were not “at the top of our list” of tools. Such a policy may be deemed illegal in the U.S. and it’s also unclear how much of an economic gain it would yield given the likely disruption it could cause to banks and money market funds.

‘Something Unnatural’

The BOE is also adverse to negative rates, even as the risk mounts of the U.K. leaving the European Union without a divorce deal. Governor Mark Carney has ruled out going below zero, arguing there is “something unnatural” about doing so as it could hurt the margins, profitability and capitalization of banks, and thus their willingness to lend.

The euro area and Japan have already gone negative. The ECB last cut its rate on banks’ overnight deposits on Sept. 12 and President Mario Draghi has signaled that’s not necessarily the floor. Officials argue that what lenders lose on profit margins they more than recoup on volume, as low rates boost demand for credit.

While the BOJ has indicated greater willingness to ramp up its easing measures, it’s also wary of the side effects on commercial banks and markets of its massive easing program.

In a survey published this week by the Bank for International Settlements, central bankers said sub-zero rates and asset purchases had helped growth and inflation, and that the positives outweighed the negatives.

To contact the reporters on this story: Enda Curran in Hong Kong at ecurran8@bloomberg.net;Catarina Saraiva in Washington at asaraiva5@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Simon Kennedy at skennedy4@bloomberg.net, Craig Stirling, Fergal O'Brien

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.