(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As a markets columnist, I don’t like writing about the spreading coronavirus. First and foremost, the news just gets worse by the day in terms of human lives lost, and I’m no epidemiologist. On top of that, the outbreak has also led to weeks of whipsawing headlines. One day, U.S. stocks will tumble as virus concerns mount. Days later, equities will reach records as virus fears ease. And on and on it goes.

The last time I checked in was Jan. 27. On that day, the S&P 500 Index dropped by the most since October and benchmark 10-year Treasury yields fell almost 8 basis points to 1.6%. At the time, a handful of sell-side strategists said the move couldn’t possibly last. I argued that investors may hate buying Treasuries at a 1.6% yield, but it might not be such a bad move, given how 2020 has started.

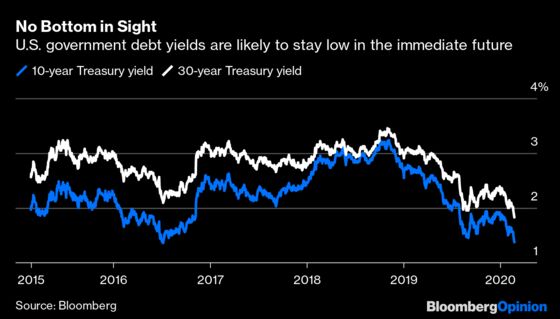

Fast-forward to today. The S&P 500 Index plunged more than 3% at one point. The 10-year U.S. yield tumbled to 1.357%, just a few basis points away from the all-time low of 1.318% set in July 2016. The 30-year yield has already set records, reaching as low as 1.81%. Traders are pricing in more than two quarter-point interest-rate cuts by the Federal Reserve in 2020 after recent data showed the first contraction in U.S. business activity since 2013, raising the prospect that even America can’t shake off disruptions caused by the coronavirus. The yield curve is the most inverted in months.

At this point, the question is no longer “why are U.S. yields this low?” but rather “how low can yields go?” My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Marcus Ashworth addressed this from his perch on the other side of the Atlantic, arguing that the U.S. could be headed toward zeroed-out yields like Europe and Japan if the coronavirus gets much worse.

Make no mistake: The news about the coronavirus is bad. It has killed more than 2,600 people so far and infected about 80,000. Italy’s financial hub, Milan — about 5,400 miles from the epicenter of the virus outbreak in Wuhan, China — is in a virtual lockdown, with the region’s schools, universities and museums closed and sporting events canceled. If that can happen in Milan, where’s next? It paints a harrowing portrait of global economic growth if large cities go silent.

But traders may want to resist jumping ahead so fast. For one, the 10-year Treasury yield isn’t even yet at a record low, let alone hurtling toward zero. The 1.318% level will surely have stiff resistance and require more than just fear and haven demand to breach. Still, it could very well happen, at which point strategists at BMO Capital Markets say to “look out below.”

More important, there are just far too many unknowns to invest with any sort of conviction. Tomas Philipson, the acting director of the Council of Economic Advisers, called the coronavirus a “real threat” but said it’s too soon to know for sure how seriously it will affect the U.S. economy. The International Monetary Fund cut 0.1 percentage points from its global growth forecast but is also looking at more “dire” scenarios. That’s hardly a clear road map.

Obviously, the thesis that governments across the world had the virus under control didn’t hold up, so stocks, bonds, gold and other assets need to price in that reality. Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Chief Executive Officer Warren Buffett may declare that lending at 1.4% “makes no sense,” but most others need to heed John Maynard Keynes’s advice that “the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.” Speculators increased their bets against long bonds in the week ended Feb. 18, according to Commodity Futures Trading Commission data released Feb. 21. That was an uncomfortable position last week; it’s downright unbearable today.

Rates strategists at NatWest Markets advocated a balanced approach to Treasuries last month when yields were tumbling: Sell a bit if you want, but keep your core position in tact. That turned out to be the right move. Here’s what John Briggs, Blake Gwinn, John Roberts and Brian Daingerfield had to say this time around:

“Yes, the bond market can and will likely over-react, but we are not yet at the time to have that discussion. With the spread of the virus into Europe, a whole new round of investor uncertainty can be unleashed, and that is what I think we are witnessing now.

...

Until we get some clarity on how to gauge the eventual economic impact off the virus, uncertainty will remain and yields will stay low. I know we’ve been a month long broken record in this space: but even if you disagree with us, we caution that in the very least you just can’t be short Treasuries until we get more clarity, and in our view, you need to continue to hold core longs.”

In other words, no record-low yield level is safe. Investors just want to own Treasuries and shed stocks.

Part of the reason for that might be because analysts are openly pondering whether central banks have the power to stave off a supply shock like the coronavirus. NatWest strategists wrote that “faith in the Fed bailing out equities should be questioned not because that’s what they tend to do, but because what they can do doesn’t do anything to fix the cause.” Jim Vogel at FHN Financial argued that geopolitical failures are “beyond the immediate reach of monetary policy.” Of course, that doesn’t mean the Fed and its peers won’t try to cure the world with lower interest rates.

That, in turn, most likely means persistently low bond yields for the immediate future. It doesn’t feel good to buy U.S. Treasuries right now. But it didn’t a month ago, either.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.