ECB’s Pandemic Program Means Most Powerful Tool Stays in Reserve

How Italy (and Others) Can Use the ECB’s Most Powerful Tool

(Bloomberg) -- European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde is doing everything she can before she has to test her predecessor’s landmark tool to save the euro.

The decision to give her own crisis measure, the week-old Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program, almost free range to buy government debt has reduced the likelihood that she’ll have to resort to Mario Draghi’s Outright Monetary Transactions

OMT remains the more powerful tool though, able to focus exclusively on individual countries, unlike PEPP or the five-year-old Asset Purchase Program. It was brought up briefly at last week’s meeting, and people familiar with the matter say there is broad support for activating it if needed.

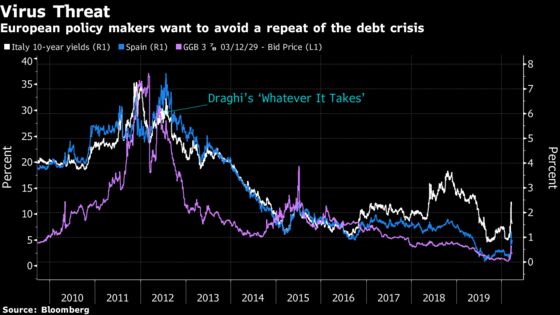

Eight years after Draghi’s pledge to do “whatever it takes” to safeguard the single currency, the ultimate bond-buying program is still in play. Here’s how it works.

Getting There

OMT allows the central bank to buy nearly unlimited amounts of government debt from stressed euro-area economies, pushing down bond yields that might otherwise make much-needed fiscal stimulus unaffordable.

It was designed in 2012 when Europe’s debt crisis threatened to break up the single currency, and the sheer existence of such a powerful measure almost immediately calmed markets. To date, not a single euro has been spent.

Now, with large sections of the economy paralyzed by the coronavirus, and governments blowing out their budgets to provide relief, the risk of another debt crisis has returned.

Italy, the hardest-hit by the virus, is the nation where rising yields are the biggest concern. The country has the second-biggest debt burden after Greece, with annual refinancing needs equivalent to 20% of GDP.

Stigma Fears

The biggest hurdle to tapping OMT is stigma. Countries first have to apply for a credit line from the euro zone’s bailout fund, the European Stability Mechanism, highlighting that they have a problem they can’t handle alone.

Finance ministers who met this week are considering offering credit lines to all 19 member states to partly address that concern. Leaders could sign off on that in a teleconference on Thursday.

A closely related issue is that unlike the ECB’s existing bond-buying programs, known as quantitative easing, OMT comes with strings attached.

That’s normally taken to mean painful economic reforms and a plan to ensure the debt burden is sustainable. Governments may agree that this time is different though, because the virus is a natural disaster.

Better Than QE

The crucial difference between QE and OMT is that QE allocates buying across the whole bloc, whereas OMT can target individual countries.

For now, there’s a middle way. QE and PEPP will top 1 trillion euros ($1.1 trillion) this year -- even more than when the 19-nation region was on the brink of deflation. The ECB has touted the “flexibility” of the programs and the signs are that it’s skewing buying toward Italy.

Even more importantly, PEPP, which accounts for 750 billion euros of that spending, will be allowed to break through the limit of 33% on how much of each government’s debt the ECB can hold. It’ll also be allowed to buy maturities as low as 70 days.

There could be even more to buy if the euro zone issues so-called coronabonds. Lagarde made a strong push for such joint debt issuance at the meeting of finance ministers, but failed to win sufficient support.

Ultimately though, both QE and PEPP holdings must be proportionate to the size of the euro area’s individual economies, a gauge known as the capital key. That means overbuying one sovereign now means purchasing less at a later point.

OMT isn’t subject to those rules -- a potential game changer if investors start to question the ECB’s resolve in defending the single currency.

Not Quite Unlimited

The program does have boundaries. Technical details outlined in 2012 stipulated that purchases would focus on the bonds with a maturity of 1-3 years.

Policy makers could of course opt to revise that. They could also change tack when it comes to an original OMT requirement that the liquidity created by purchases be reabsorbed by market interventions elsewhere to ensure they don’t fuel inflation.

Crunch Time

It’s difficult to say when or if the ECB will resort to OMT. The gap in yields between riskier and safer debt is nowhere near 2012 levels just yet, and PEPP has bought the central bank time to see how the emergency pans out.

The recession could be severe though -- some economists predict a drop in output of as much as 5% this year, the biggest in the euro zone’s two-decade history.

The test for Lagarde is whether the ultimate monetary tool is best deployed, or held as a reminder that if governments fail to deliver a way out of the crisis, the ECB will stand by Draghi’s pledge

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.