One Old Rivalry Where Hong Kong Can Beat Singapore

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Hong Kong and Singapore, two of Asia’s most open, small economies, are always jostling to stay a step ahead of each other, except when it comes to their pension systems. The thinking in Hong Kong seems to be one of wistful admiration for Singapore’s Central Provident Fund.

Yet, in this instance, envy is counterproductive. While there is no doubt that Hong Kong’s Mandatory Provident Fund needs a revamp, aping Singapore should be off limits. That would inject a statist component into Hong Kong’s freedom-loving DNA. With the Big Brotherly presence of Beijing becoming a little heavier every passing year, Hong Kong needs to worry about what it may lose in the long term by chasing more retirement wealth in the short run.

CPF and MPF. Both operate by defining contributions and making them mandatory for a majority of workers. Beyond that, there are many differences, starting with how they have evolved. After three decades of debating whether and how to give private-sector employees an avenue to save for old age, Hong Kong set up its MPF in 2000. That was three years after the British-run city’s handover to China, as a special administrative region pending full integration in 2047.

By the time the MPF was born, Singapore’s CPF, started by the British colonialists in 1955, had already become an important tool for economic and social engineering under the island’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew.

Starting in 1968, Singaporeans could borrow from their CPF savings to invest in housing. Over time, this gave rise to near-universal home ownership in the city-state. Of course, it has also meant higher contribution rates by both employers and employees. In arguing the case that Hong Kongers’ monthly HK$3,000 ($382) pension payment is inadequate, the Financial Services Development Council, or FSDC, recently invoked its long-standing rival. Singaporeans’ monthly cut is 3.2 times higher, the government advisory body noted.

Simply ordaining higher old-age savings isn’t enough. People will want to know the trade-off from forgoing current consumption. A Singapore-style drawdown for paying Hong Kong mortgages is often discussed. But to introduce a new source of housing demand could make prices in the world’s most unaffordable property market go off the charts. Much as youngsters in Hong Kong want to own the roof over their heads, leave out use of superannuation funds for housing as impractical for now.

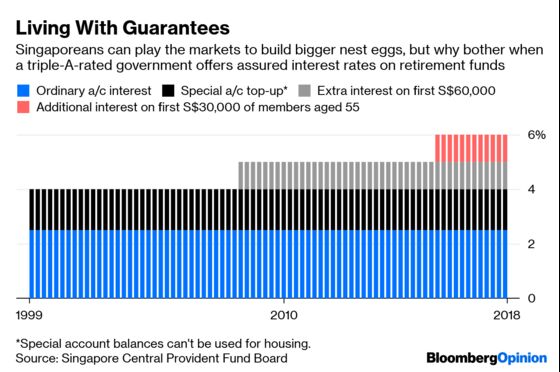

If the option of real-estate wealth can’t be dangled, Hong Kong has to summon up the other ace Singapore has up its sleeves – a guaranteed minimum interest rate of 2.5 percent, which rises to 4 percent on savings people promise not to use for housing. Everyone gets 1 percent top-up interest on part of their balances. Older workers get even more.

The CPF can afford the undertakings because it takes the pension savings and hands them over to the government, which is legally prohibited from using them to plug budget deficits. The money is commingled with state funds, and given to GIC Pte, the Singaporean sovereign wealth fund, which makes a return by investing in assets worldwide.

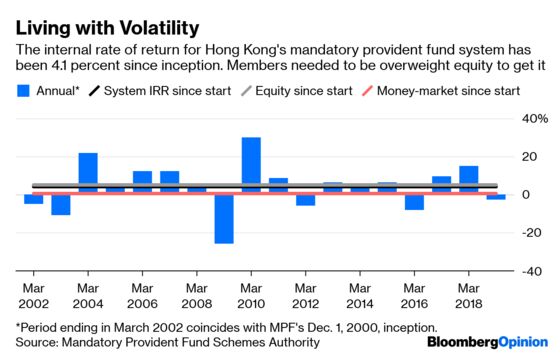

Hong Kong has none of this. The MPF is a private arrangement; the savings go to asset managers like Fidelity Investments and Allianz SE, based on the employees’ selection of equity, fixed-income or money-market funds. The systemwide annual returns of 4.1 percent a year since 2000 aren’t bad. But we don’t know what percentage of members are able to earn it. Meanwhile, fees and expenses that average 1.5 percent across plans seem excessively high.

The FSDC’s suggestion of a centralized e-MPF, with easy portability between plans, supported by independent-minded fund trustees not beholden to the shareholders of sponsor firms, will go some way toward redressing the grievance about fees. Tax breaks on contributions in excess of the prescribed amounts would shore up voluntary investment, which are currently just a fifth of the mandatory minimum. But the question about state-guaranteed returns will linger.

Is it possible – or desirable – for Hong Kong to build an institution like Singapore’s GIC from scratch? The alternative, parking the savings at the central bank’s exchange fund, whose main job is to defend the peg of the local dollar to the U.S. currency, would be risky. Already there is crazy talk about letting the fund invest in China’s Belt-and-Road Initiative. Hitching Hong Kongers’ superannuation to Beijing’s strategic bandwagon just for a guaranteed return would be controversial in the city’s current political climate.

The simplest solution for Hong Kong is to accept that the MPF will never be the CPF, and that the financial services council’s modest suggestions for tweaking the system’s efficiency are enough for now.

Singapore’s guarantees recreate returns from a 60 percent global equity portfolio but minus the downside risk, independent research has shown. The guarantees are designed to be sweeter still in case global interest rates rise. Yet many Singaporeans complain about not getting a fair shake, even though most individuals lack the acumen and the risk-taking ability required to beat the current setup.

So should Hong Kong accept defeat? Not really. It can do better than Singapore by embracing that one idea it rejected in the run-up to the MPF in 2000: a universal basic pension, a defined benefit. The concept was ahead of its time when the Legislative Council debated it. But not any more. Hong Kong’s annual budget on Wednesday would be a good occasion to start a conversation about how taxpayers, employers and employees could come together to sustainably finance a minimum livelihood to pensioners.

Singapore just announced a yearly S$8 billion ($5.9 billion) package for the generation born in the 1950s. That’s on top of the S$9 billion it’s spending on people who are even older. But if Hong Kong can vouchsafe a basic livelihood for today’s workers in tomorrow’s robot-dominated world, it would steal a march on its rival. For that, Hong Kongers would gladly accept higher pension contributions. And a little more of the state in their private lives.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services. He previously was a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He has also worked for the Straits Times, ET NOW and Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.