High Debt. Low Growth. Are We All Japanese Now?

Asia’s second-largest economy holds lessons for the rest of us as Covid-19 destroys jobs and rocks whole industries.

(Bloomberg Markets) -- Cocooned in the mountains of Nagano, Japan, employees at Ina Food Industry Co. begin the day by tidying the garden around their office and factory buildings. The smell of freshly cut grass perfumes the summer air as loudspeakers pipe out the company song: “… surrounded by the green of pines, showered by the happiness of the morning sun, the gathering of our comrades. … ”

As usual, the company’s patriarch, Hiroshi Tsukakoshi, who turns 83 in October, greets his employees, reinforcing the sense of community and security he’s created over more than six decades of running the business while never cutting a single job. And he doesn’t plan on doing so now, even as the Covid-19 pandemic causes the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

Tsukakoshi has told his workforce of 500 or so that all their jobs are safe. Even though sales are forecast to be down about 15% this year, he says, Ina Food’s employees will still get modest annual raises and their traditional summer bonuses. “If a company grows in volatile fits and starts,” he says, “people are increasingly gripped by fear and fret over when they will be fired. You have to maintain incremental growth to keep your people happy.”

That approach to doing business has made Ina Food, which produces a gelatinlike substance called agar from algae, something of a poster child for success in Japan’s low-growth economy. Akio Toyoda, president of Toyota Motor Corp., has toured the company and touts a book Tsukakoshi wrote on management. In the reception area where Tsukakoshi greets visitors, a photo on display commemorates the time Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda stopped by in 2015.

Ina Food represents a sepia-toned, somewhat idealized side of the world’s third-biggest economy—one that offers a dose of optimism to a world that may be headed down a similar trajectory of high debt, endless stimulus, and anemic growth. After 30 years of flat-lining, the country still boasts one of the developed world’s best living standards and a jobless rate of just 2.9% in July.

“Japan is like a family that didn’t go on vacation but built up a bank account,” says former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, a paid contributor to Bloomberg TV. “The consequence is the family will be in a better place when Dad becomes unemployed.”

In recent times, global policymakers had come to see Japan more as a cautionary tale than an economic role model. But as the pandemic destroyed tens of millions of jobs around the world, that view has shifted, with some economists considering whether the Japanese model is in fact a template well-suited to current conditions.

Amid the Covid-19 crisis, thousands of companies were able to keep their doors open and employees on their books this year—and over the past 30 years, for that matter—thanks to cheap loans and the lingering jobs-for-life culture. Summers says longtime critics should be “a little bit more humbled” as Japan’s low-growth, low-interest-rate trend becomes a norm in Europe and the U.S.

But there’s another, grittier side to the Japan story. For almost every Japanese worker enjoying the kind of job security that’s a distant memory in most other industrialized nations, there’s somebody toiling in a low-paid role with no such protection.

Tatsumi, a 36-year-old single mother who asked to be identified by her family name only, is one such person. She lost a dishwashing job that paid 1,000 yen ($9.46) an hour in June when the pandemic shut the restaurant where she worked in Hyogo in the center of the country. “They used me like a pawn when business was good,” she says.

Tatsumi is part of Japan’s underclass. Over the decades of stagnation, companies have resorted to part-timers, contractors, and seasonal workers to cut costs. Known as nonregular workers, with little job security and few benefits, they make up roughly 40% of the labor force. About 70% of them are women.

Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who in mid-September resigned because of a worsening chronic medical condition, had touted a record female employment rate—71% for women age 15 to 64 in 2019—as a key success of his economic policy as many women who were previously out of the workforce joined the rank of nonregular workers.

The crisis has revealed how shaky those gains were. The number of jobs held by nonregular workers fell by more than 1 million in the first half of the year, even as regular jobs rose by 450,000 because of companies sticking to their traditional practice of hiring new graduates in April.

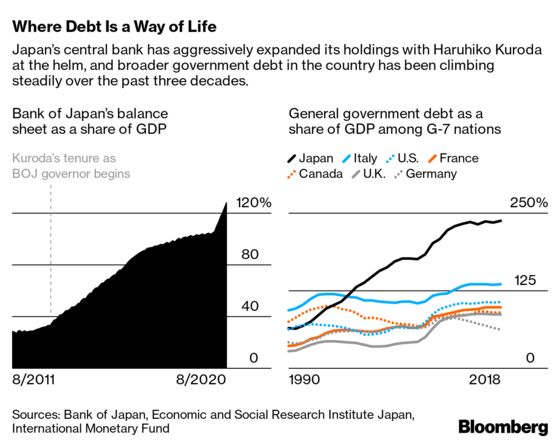

Productivity and innovation in Japan have long lagged Northeast Asian neighbors such as South Korea and China. A barrage of government spending programs and decade after decade of monetary stimulus from Kuroda and his predecessors failed to create robust, sustainable growth, leaving Japan with the world’s largest pile of public debt.

A key question now is this: Will Japan’s economic strategy leave its businesses and households better positioned to drive a modest recovery once the virus is contained?

A distinctive characteristic of the Japanese economy is that, while the government has borrowed, its companies have done the opposite. Retained earnings at companies stood at 459 trillion yen at the end of June, or more than 90% of gross domestic product. They’re up 72% since the fourth quarter of 2008. “Money supply and demand don’t get balanced unless the government spends massively,” says Kazuo Momma, a former BOJ director who now works as an economist at Mizuho Research Institute. The pandemic is set to accentuate that trend further, he says.

A similar pattern can be seen globally. As the pandemic persists, governments are being pressured to boost the trillions of dollars of fiscal stimulus they’ve already doled out. U.S. public debt is projected to surpass records set in the post-World War II years by 2023, while U.K. government debt rose above 100% of GDP in May for the first time since 1963. In Japan, where the debt-to-GDP ratio is already above 200%, the government doesn’t expect its budget to be balanced until at least the end of the current decade.

Ina Food has held on to enough cash from its profits to keep everyone on the payroll this year. As a private company, it can do that because there are no shareholders demanding dividends, and Tsukakoshi and his eldest son, Hidehiro, who now runs the company as president, say they plan to keep it that way.

Many public companies have also been socking money away. As president of Nitto Kohki Co., a machinery-parts maker listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, Akinobu Ogata has faced pressure from shareholders to use the company’s abundant cash to boost dividends. It had retained earnings of 52 billion yen at the end of March—almost twice its annual sales and about 30 times what it spent on capital investment last fiscal year.

“We protect jobs 100%,” Ogata, 66, says of his 1,000 or so employees, some of whom have been put on paid leave as factory operations have been cut back. “We want sustainable growth, even if it looks dull.”

Until the early 1990s, Japan’s economy was anything but dull. Its companies were busy buying trophy assets around the world, such as Pebble Beach Golf Links in California and Rockefeller Center in New York. Sony Walkmans and Toyotas epitomized its manufacturing mastery. The Hollywood film Gung Ho, starring Michael Keaton, portrayed the fictional clash of cultures when a Japanese corporation took over a U.S. car plant. In late 1989 the benchmark Nikkei Stock Average peaked at almost 40,000 and soon plunged as the asset bubble hit its limit, bringing down property prices. Then the entire economy started falling to pieces. In the meantime, Asian Tigers such as South Korea and China emerged.

Now Japan, like just about every other country in the region, finds its supply chains deeply entwined with Chinese suppliers. When imports of machinery parts from China stopped in late January as Beijing moved to contain the novel coronavirus’s spread, Nitto Kohki started looking for alternative partners in its neighborhood of Tokyo’s Ota ward, home to 1,207 factories in 2018, more than any other of the capital’s 23 districts. The machinery-parts maker turned to Johnan Shinkin Bank for help.

Along with dishing out government-backed loans to save businesses, Johnan Shinkin has been directing the employers to government rescue measures such as special cash handouts and job retention subsidies. Cheap and abundant money from the BOJ means small lenders can keep credit lines to their borrowers open, even as the low margins caused by ultra-easy monetary policy squeeze Johnan Shinkin’s own profitability. “We are a community bank,” says President Kyoji Kawamoto. “When our community goes down, we will also go down.”

The pandemic has exacerbated problems that already existed here. As in the Rust Belt areas of the U.S. or Europe, Japanese manufacturers have been clobbered by cheap labor and production in China and elsewhere. The number of factories in Ota, for instance, has dwindled steadily from a peak of 5,120 in 1983. “Toward the end of this year, businesses will have used up loans unless the situation improves,” says Kawamoto. “They will probably think about whether to borrow more or quit.”

The bank managed to connect Nitto Kohki with Fujisokuhan Co., a machinery maker with about 40 employees that operates in the middle of a residential area about a mile away. Fujisokuhan’s president, Keiji Shinohara, says he hopes the new partnership with Nitto Kohki will help his business. Unlike Tsukakoshi of Ina Food, he had to cut summer bonuses about 30%.

Like many of the aging owners of the diminishing number of factories in Ota, Shinohara, 67, doesn’t have his successor lined up for the company his father founded half a century ago. “That’s the biggest problem, and I don’t know what to do about it,” he says. “Many companies in Ota are run by old people. They are keeping up their businesses until they or their machines break down.”

The outlook for the companies of Ota says much about Japanese policy. While the endless drip of stimulus and an increase in support during the Covid-induced slump has kept struggling businesses afloat and prevented mass joblessness, the surviving companies may not be profitable in the long term, even in a post-pandemic world. What’s more, these government safety nets just postpone the kind of structural reforms needed to boost productivity and economic growth as the country’s workforce shrinks because of aging.

“Japan’s incremental style has downsides,” says Nomura Research Institute economist Takahide Kiuchi, a former BOJ board member who’s been a staunch critic of Kuroda’s aggressive monetary easing. “It’s very inefficient to continue to pour tax money into companies whose profitability won’t fully come back. Surging fiscal spending is hindering Japan’s growth potential in a way. You can’t keep going like this. And you shouldn’t.”

That surge in fiscal spending has been supported by the central bank’s unlimited bond buying, something echoed this year in Europe and the U.S. along with most other advanced economies and some emerging ones. Like its peers elsewhere, the BOJ buys the bonds in the secondary market, meaning it isn’t directly financing the government’s deficit as proponents of Modern Monetary Theory would argue for.

But such seemingly endless stimulus can’t necessarily be replicated, because most other nations don’t have such a vast domestic savings pool or Japan’s status as a net lender to the world.

“There’s no uniform standard among nations in terms of how far a government can go into debt,” says Mizuho Research Institute’s Momma. “There are countries that can easily go down if they issued debt like Japan,” he adds, without specifying which ones.

Whatever the people in power do, Tatsumi, the single mother who lost her job as a dishwasher, wants them to do it fast. Abe had announced economic stimulus packages worth more than 40% of GDP, adding to the already massive debt burden. On April 6, on the eve of the declaration of a state of emergency because of a rising number of Covid infections, Abe said needy households like Tatsumi’s would get 300,000 yen. Ten days later he changed course, promising 100,000 yen per citizen regardless of income. Then red tape delayed the cash injection. “It was very slow,” she says. “They flip-flopped. I was thinking, Whatever. Just move fast.”

In April, when she was put on a furlough and told her three-month contract wouldn’t be renewed, Tatsumi was one of about 4.2 million people who showed up in government labor statistics as not working even though they were still technically employed. Had they been counted as unemployed, the jobless rate would have been 11.5%, not the official figure of 2.6% in April.

During her furlough, Tatsumi’s employer at the restaurant paid 60% of her salary as required by law, but she still had to tap savings she’d set aside to pay for her two sons’ higher education. She found a new job as a cook at a nursing facility for the elderly; if nothing else, she figures it’s a safe job thanks to Japan’s aging population. But it’s another part-time job. At 950 yen an hour, it doesn’t pay as well as her previous one, and she’ll be working fewer hours. “I really feel I am not protected by Japan’s system,” she says.

Life seems more predictable and secure for Miho Ikeda, a 35-year-old Ina Food researcher who develops methods of making jelly, pudding, and noodles out of agar. She says her sense of job security has enabled her to make some of the biggest decisions of her life, including marrying a co-worker in 2012, building a house four years later, and having a son in 2018. “I see my future very clearly,” she says.

For the world’s virus-battered economies, one of the few things that’s clear is that they’ll be saddled with record debt levels and subjected to emergency policy settings for years to come as they seek to grind their way back to health. “Secular stagnation will contribute to the Japanification of the global economy,” says Summers. Thirty years of Japanese economic history demonstrate what that looks like.

Nohara covers economics from Tokyo.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.