Health-Care Paradox Threatens to Add to Japan’s Debt Problems

Japanese seniors, who enjoy the longest life expectancy, pay as little as 110 yen ($1) out of pocket for specialist appointments.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Atsuko Arai sees a doctor as many as a dozen times a month. The 75-year-old Tokyo retiree has no chronic conditions; she sees these sessions as a way to stave them off. “If I go to the doctor at the frequency I do, I won’t get so sick that I need medication,” she says.

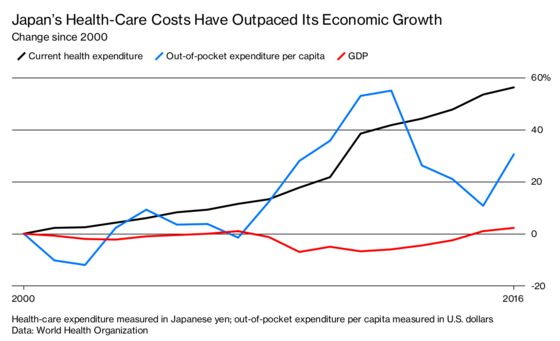

Japanese seniors, who enjoy the world’s longest life expectancy, pay as little as 110 yen ($1) out of pocket for specialist appointments. While these visits may help prevent expensive-to-treat diseases, they’re becoming unaffordable in a country where almost 1 in 7 people is 75 years or older, and annual health-care expenditure grew at a pace 40 times faster than the economy from 2000 to 2016.

“The financial resources are limited, but people expect higher-quality medicine every day,” says Shigeru Omi, a doctor who headed the World Health Organization’s Western Pacific Region for a decade and now leads a Tokyo-based agency that manages a chain of 57 hospitals. “This is the dilemma. How do you balance the two?”

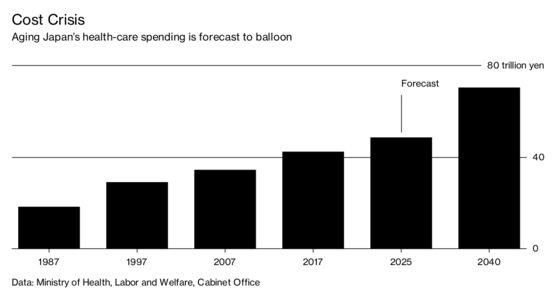

That’s a pressing question in a country burdened by the largest sovereign debt of any industrialized nation and a shrinking taxpayer base. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said in October that his administration is looking to avert a “national crisis” by implementing measures to tame runaway spending on health and other social services. Government projections show costs topping 70 trillion yen ($620 billion) by 2040, a 66 percent increase from 2017.

The success of any reform push will depend on the state’s ability to persuade patients and those profiting from medical services and treatments to accept a more sustainable model—one ideally based on fewer expensive specialist visits and diagnostic tests.

In contrast with the U.K., Australia, and other countries that run national health services, Japan has patched together a more-or-less universal coverage system that relies on an assortment of private and public medical facilities, thousands of insurers, and powerful professional groups representing doctors and pharmacists. Patients are responsible for copayments but have the freedom to choose their doctors and the frequency of consultations. The system also encourages doctors to squeeze in as many patients as possible.

The need to negotiate with that complex web of vested interests limits policymakers’ scope for drastic changes. Resistance from patients such as Arai is another risk factor for the Liberal Democratic Party government. Even though Japanese seniors typically have healthy lifestyles, people over age 65 account for almost two-thirds of medical expenditure—a bill the Institution for Future Welfare, a Tokyo-based think tank, says totaled 24.8 trillion yen in the fiscal year ended March 2016.

“It’s the elderly who go out and vote, so if they do something that makes them angry, they will lose elections,” says Hiroyuki Kishi, a professor at Keio University in Yokohama who has advised various government ministries on matters such as industrial policy and energy. Nevertheless, Kishi says, Japan’s leaders have to act. “If they don’t manage a root-and-branch reform, the social security system as a whole won’t hold up,” he says.

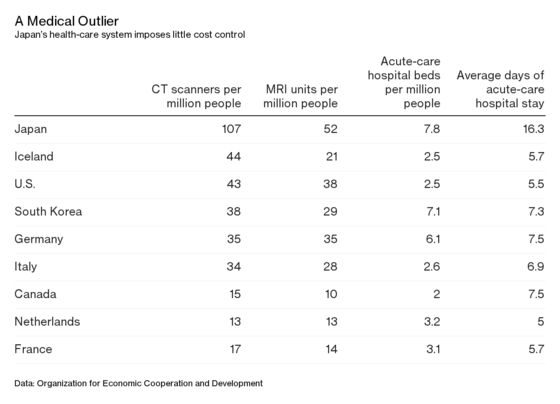

One reason Japan’s health-care costs have been rising at such an alarming rate is that the majority of its 311,000-plus licensed physicians work in hospitals, where patients often seek treatment for even mild symptoms in the absence of a “gate-keeping waiting-list system” without first having to consult a primary care doctor, according to a 2018 review written and edited by more than a dozen public health researchers in Japan. That helps explain why the Asian nation’s installed base of hospital beds and sophisticated diagnostic equipment, as well as duration of hospital stays, well exceeds the average among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries.

“The problem with the system is the government is paying for it, but no one is checking what the doctors are doing,” says Ray Fujii, Tokyo-based partner at L.E.K. Consulting, which provides advice on management including to the health-care industry. “Any medical system that relies on the willingness and goodness of the doctor is not going to work, and that’s what it is here.”

The lack of coordination among physicians is a consistent theme discussed at conferences, says Jeff Schnack, president of Tokyo-based health-care consulting firm C3 KK. He recounts a case in which a doctor discovered a patient had 17 prescriptions from eight clinics and hospitals. “No one knew what he was taking, and there were problems with drug interactions and so forth,” he says.

A computer network linking prescribers and pharmacists with individual patient records—a system the Ministry of Health plans to implement in 2020—could improve oversight and patient safety. Yet government technocrats recognize that convincing health-care providers and patients to sign up for the service may be a challenge because of patient privacy concerns and the cost of installing and maintaining computerized records. “We can’t force them to do it,” says Kouta Tagawa, a deputy director in the ministry’s research and development office. Some incentive may be required to get providers and patients to use the service, potentially adding to costs, he says.

Abe announced plans last month to provide incentives for insurers to play a greater role in preventing lifestyle-related diseases such as Type 2 diabetes, which is less common in Japan than in the U.S. or China. Another government initiative aims to promote the use of family doctors or general practitioners. Greater reliance on primary care may reduce costs by cutting down on unnecessary specialist consultations and tests while improving patient safety and enhancing access to health care in rural and remote areas, according to Omi, the former WHO regional director. To bolster the pipeline, some medical institutions began offering specialized training for general practitioners in April.

“Good access to care leads to better health only when the quality of care is high,” says Yusuke Tsugawa, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California at Los Angeles. Tsugawa trained as a doctor in Tokyo and spent a stint as a health specialist with the World Bank before completing a doctorate in health economics at Harvard. A redesign of the health system “is imperative” for Japan to clamp down on overservicing, he says.

“It’s just going to get so much worse with the graying society and the tax base dropping,” says Schnack, the health-care consultant. “It’s going to be hard to maintain anything near the current standard moving forward.” —With Yuki Hagiwara

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jason Gale at j.gale@bloomberg.net, Cristina Lindblad

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.