Hawkish Fed, Dovish PBOC Diverge in New Phase of Policy

The U.S. and China are set to spend 2022 diverging on monetary policy.

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

The U.S. and China are set to spend 2022 diverging on monetary policy, marking a new phase in the struggle to deal with the fallout of the pandemic and setting up a synchronized slowdown in the world’s two largest economies.

As the Federal Reserve lines up to start raising interest rates from near zero to curb the strongest inflation in four decades, the People’s Bank of China is stepping up support for an economy under strain from a property market crackdown. In the latest move, Chinese banks lowered borrowing costs for the first time in 20 months Monday.

Higher U.S. rates will dampen demand in America while China merely cushions -- rather than stimulates -- its own sputtering economy. Growth between both economies could start converging if the U.S. follows China’s 2021 slowdown, though the omicron variant is a new wildcard for both central banks.

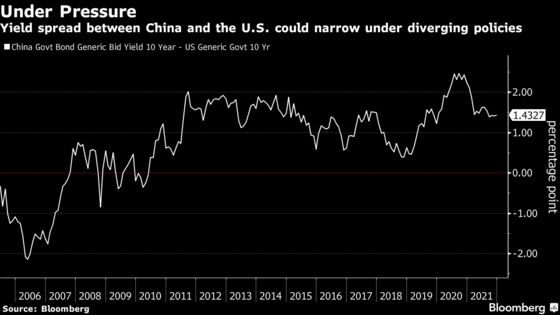

Each central bank’s pivot carries risks and have potential implications for international capital flows. The yuan’s strength and record inflows of foreign capital into China will be tested if a hawkish Fed means the dollar strengthens, bond yield differentials narrow and investors rebalance portfolios.

“If the Fed is pivoting towards a more hawkish stance and the PBOC is easing, this will shift the expectation of relative tightness in monetary policies in the U.S. versus China,” said Helen Qiao, chief economist for Greater China at BofA Global Research. “The immediate implication is on foreign exchange as we may start to see some depreciating pressure on the yuan relative to the dollar,” she said.

Much will ultimately depend on the pace of tightening that the Fed pushes through and how far China goes with easier policy.

For now, economists predict the Fed will carry through on its plan to end its asset-purchase program and satisfy its new projections for three rate hikes in 2022.

Meanwhile, analysts expect the PBOC to accelerate credit growth after almost a year of slowing, and there is rising expectation that it will further cut the amount of cash banks must hold in reserve -- called the reserve requirement ratio -- in coming months.

What Bloomberg Economics Says ...

“Potential paths for China’s interest rates ... and faster than previously signaled increases for the Fed mean that the yield gap between yuan and dollar assets is likely to narrow more.”

-- Chang Shu, chief Asia economist

Click here for full report

Calls for a rate cut have also been gaining momentum, which will narrow the yield spread between U.S. Treasuries and Chinese government bonds.

The one-year loan prime rate was set at 3.8% versus 3.85% in November, the first reduction since April 2020, according to a statement from the People’s Bank of China on Monday.

Policy divergence could lead to less capital flowing into China “but the impact is likely to be more muted than previously,” said Mitul Kotecha, chief EM Asia and Europe strategist at Toronto-Dominion Bank.

Pandemic Policy

The pandemic has put China’s monetary policy in sharp contrast with the rest of the world. As the first economy to enter a lockdown-induced slump last year, it was the first to begin recovering as well while the rest of the world was still struggling to emerge from recession.

Worried that loose monetary and fiscal policy would fuel financial risks, Chinese authorities began tapering stimulus and tightening rules on lending in the property market this year. That triggered debt defaults, a slump in housing sales and investment, and weaker economic growth -- a slowdown that policy makers want to avoid worsening as the Communist Party heads for a crucial leadership meeting in 2022.

“The Chinese and U.S. economies are in different stages of the business cycle,” said Ding Shuang, chief economist for Greater China at Standard Chartered Plc. “China has taken a lead with tightening this year, and next year it will start to boost domestic demand, and growth is expected to stabilize.” The U.S. on the other hand “will begin to slow next year, but will still remain above the trend growth rate,” he said.

| Read More on the Topic: |

|---|

|

Surging trade surpluses -- which will likely continue at least into the first half of 2022 -- will give underlying support to the yuan and provide space for the PBOC to let it depreciate somewhat, while much more stringent capital account controls will prevent a repeating of large money outflow five years ago.

“Factors that have kept the yuan strong, such as the large trade surplus, brought by surging exports and weak domestic demand and little outbound tourism, are likely to remain intact in the near-term,” said Alejandra Grindal, chief international economist at Ned Davis Research Inc.

For the global economy, the central banks’ different paces could turn out to be helpful in avoiding overheating, and lead to converging growth between the two countries, according to Chua Hak Bin, senior economist at Maybank Kim Eng Research Pte. in Singapore.

The two largest economies in the world “may offset each other and have a balancing effect on the global economy overall,” said Standard Chartered’s Ding.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg