Goldman, Morgan Stanley Do Better in Fed Stress Tests After 2018’s Stumble

Goldman and Morgan Stanley improved on last year’s poor results in the first round of the latest Federal Reserve stress tests.

(Bloomberg) -- Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Morgan Stanley improved on last year’s poor results in the first round of the latest Federal Reserve stress tests, a sign they may have more flexibility to boost payouts to shareholders.

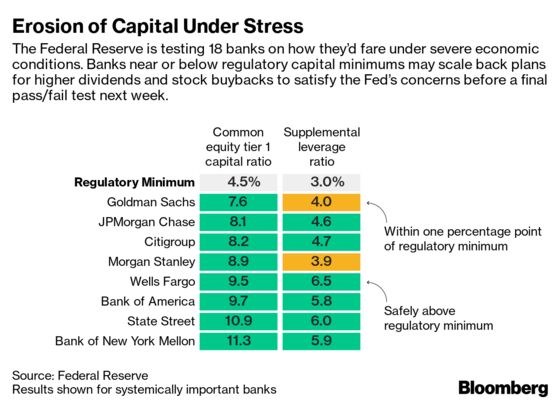

In figures posted Friday by the Fed, the pair didn’t come as close to breaching regulatory minimums as they did last year, offering hope they will escape limits on dividends and stock buybacks imposed back then. All 18 banks in the exam demonstrated an ability to withstand a hypothetical financial shock. The second and final round next week determines whether firms win approval to boost capital payouts.

Results posted so far show banks are getting better at coping with what’s become one of the most rigorous supervisory efforts: They maintained a collective common equity Tier 1 ratio that was double the regulatory minimum even at the depths of the theoretical recession. Lenders have been building capital for years, and while this year’s exam was harsher on credit-card loans, trading losses were down from last year at four of the five biggest Wall Street firms.

Still, when the process wraps up next week, analysts expect big banks to slow the expansion of payouts to shareholders after two years of surging dividends and buybacks.

Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley were allowed to dip below the required minimums in the second part of last year’s test because some of the decline was a result of one-time charges related to the 2017 federal tax overhaul. After next week’s round, Goldman is expected to modestly reduce its total payout in dollar terms while Morgan Stanley modestly increases it, according to analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg before Friday’s results.

This year, Goldman Sachs’s supplementary leverage ratio fell to as low as 4% in the first round of the Fed’s test, an improvement from 3.1% last year. Morgan Stanley’s ratio was 3.9%, compared with 3.3% last year. To carry out proposals to distribute capital, banks need to remain above 3% by that measure in next week’s test.

Taking ‘Mulligan’

Lenders are given a chance to adjust and resubmit their cash distribution plans before the second set of results is released June 27. A record number of firms used the so-called mulligan last year to adjust their original payout requests to stay above the minimum requirements.

The 12 largest U.S. lenders tested are expected to boost payouts by $5 billion in the next four quarters, after dividends and buybacks jumped by more than $30 billion each of the past two years. Still, the increase means they’ll likely pay out more than 100% of their annual profit.

In past years, some banks had initial proposals for payouts reined in after they projected their capital and leverage ratios would hold up better than what the Fed calculated. In some cases, the Fed even took issue with the strength of their capital planning.

This year, a half dozen firms including Bank of America Corp. posted internal calculations that were instead lower than the Fed’s, indicating they were even more conservative than examiners. Still, several companies were more optimistic. Morgan Stanley, for example, calculated its leverage ratio would be 1.7 percentage points higher than what the Fed found.

Altogether, the 18 banks tested would suffer a $115 billion pretax loss in the severely adverse scenario, the Fed said. That amounts to 0.8% of the banks’ average assets, the same ratio as under last year’s test. Their hypothetical revenue before provisions and trading losses was projected by the Fed to be 2.4% of assets, down from 3% last year.

A steeper yield curve foreseen in last year’s scenario helped prop up pre-provision revenues because banks make more money when the gap between short-term and long-term rates widens. The change in assumptions about interest rates this time helped banks book gains in their Treasury portfolios even as it lowered their pre-provision revenues.

Credit Cards

This year’s stress scenario featured a harsher hypothetical recession and the worst increase in unemployment used in the tests so far, yet its stock- and bond-market losses were less severe than last year. That helped Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, which derive more of their income from securities trading than lending.

Historically, losses tied to credit cards and commercial loans tended to be similar amounts. But this year, losses tied to cards under the central bank’s severely adverse scenario reached $107 billion, outpacing the $73 billion in losses produced by their commercial counterparts.

The central bank said credit-card loss rates increased “due in part to the final phase-in of changes to the supervisory credit-card model.” That model changed how Fed treats uncollected interest and fees at the time of default.

Foreign Banks

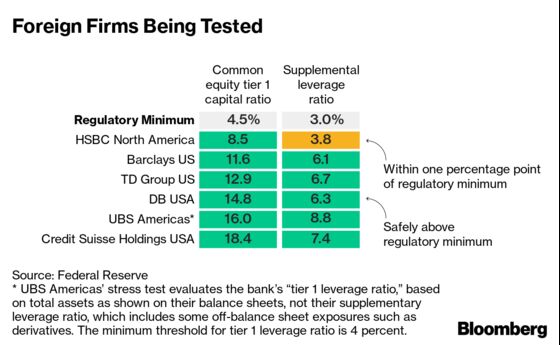

Friday’s results also included what would happen to the capital ratios of six foreign banks’ U.S. units under the same scenario. HSBC Holdings Plc’s U.S. arm saw its leverage ratio fall to within a percentage point of the minimum, the narrowest margin in this year’s group. Next week, units of foreign banks also face a qualitative evaluation of their risk management, data-collection capabilities and capital planning. That’s where some of them could trip up.

Foreign firms failing the test can’t repatriate profits earned in the U.S. to their parent companies. For Deutsche Bank AG, whose U.S. units have failed the test three times already, a failing grade will be yet another blow to investor confidence as it struggles with restructuring efforts and profitability. The Fed placed the firm’s U.S. arm on a list of troubled lenders last year because of deficiencies in its internal oversight.

The exams are in flux because the Fed is working on a rule that will more closely marry the stress testing process with day-to-day capital decisions at the banks. And the agency has tried to make the regime more transparent -- an effort that has accelerated amid President Donald Trump’s deregulatory agenda.

As part of that effort, Congress passed a law last year ordering less strict treatment of smaller banks. That prompted the central bank to ease the stress test burden on a dozen regional U.S. lenders and half a dozen smaller foreign banks, which are now tested every other year and weren’t included in this year’s exercise.

--With assistance from Jenny Surane and Gregory Mott.

To contact the reporters on this story: Yalman Onaran in New York at yonaran@bloomberg.net;Jesse Hamilton in Washington at jhamilton33@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Michael J. Moore at mmoore55@bloomberg.net, ;Jesse Westbrook at jwestbrook1@bloomberg.net, David Scheer, Dan Reichl

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.