Record Ice Loss in Greenland Is a Threat to Coastal Cities Worldwide

The changes in Greenland’s ice makeup “are truly astonishing,” Thomas Frederikse, a NASA scientist, said.

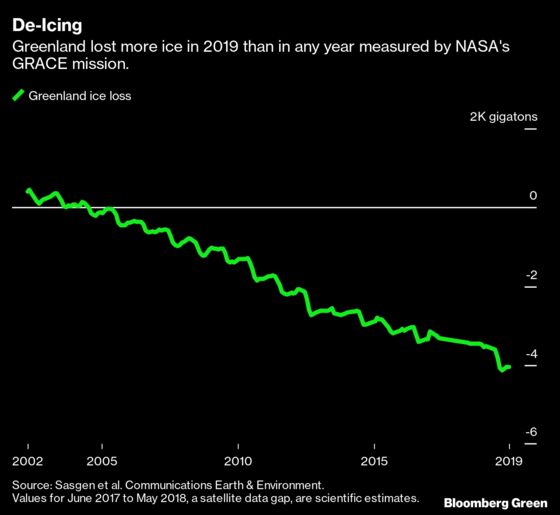

(Bloomberg) -- Greenland broke its 2012 record for ice loss last year by 15%, a startling sign that a major contributor to global sea-level rise may be accelerating.

On its own, ice loss from the world’s biggest island is responsible for more than 20% of sea-level rise since 2005, according to new data published Thursday. That includes ice breaking off from the land and floating off and ice that melted directly into the water. It’s also about the same contribution as all the world’s other glaciers combined.

Another study about sea-level rise published Wednesday corroborates that conclusion. It also finds that another 40% of the oceans’ rise since 1993 can be attributed to rising temperatures, which cause water to expand.

Together, the results are important beyond just the community of scientists who study ice. Once that becomes water, it begins a journey that’ll lead it to New York Harbor, Miami Beach, Tokyo, Shanghai, London, and the world’s other vulnerable coastal cities as higher tides and greater flood risk.

The changes in Greenland’s ice makeup “are truly astonishing,” Thomas Frederikse, a NASA scientist, said about the new ice-loss data. The Greenland study, which he’s familiar with but wasn’t a part of, shows that “during 2019, Greenland alone caused as much sea-level rise as was caused by all processes combined in an average year during the 20th century,” he said.

Ingo Sasgen of the Alfred Wegener Institute and the Greenland paper’s lead author said he was surprised that the 2012 record was eclipsed in just seven years. The rates of melt were actually similar, he said, but 2019 saw less snowfall to compensate for the ice lost.

“I am starting to get used to higher and higher mass loss rates, which makes sense because the warming continues in the Arctic,” he said. “But obviously this is not a good thing, as this will eventually mean sea-level rise caused by the Greenland ice sheet is accelerating.”

The data about last year’s ice loss was published Thursday by an international team in the journal Communications Earth & Environment. The study bridges a gap between two NASA missions involving satellites that monitor the flow of water around the planet.

The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment launched in 2002 on a mission to map variations in the Earth’s gravity. It lasted until June 2017, well past its expected lifespan, and collected years of data about shrinking ice sheets and declining groundwater resources by picking up on minute gravitational changes. A sequel mission, GRACE-FO (for “Follow On”), launched in mid-2018, but that left scientists without meaningful data for almost a year in between.

Sasgen and his colleagues analyzed what happened during the 11 dark months between the loss of GRACE and the launch of GRACE-FO. They concluded that the period saw an unusual slowing in the rate of ice loss. From 2003 to 2016, Greenland shed about 255 billion metric tons (gigatons) of ice a year. Regional weather oddities in 2017 and 2018 caused that loss rate to fall by more than half, to about 100 GT a year, before it bounced back up in 2019 to 532 GT.

NASA’s Frederikse led a different study, published Wednesday in Nature, that reconciled the amount of sea-level rise scientists have observed with the sources of it going back to the year 1900. The work will allow scientists to be more confident in their estimates of sea-level rise for the years and decades ahead, he said. The last time the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a major scientific assessment in 2013, the rate of sea level rise was a meddlesome question.

“This is one of the puzzle pieces that was still missing,” he said. “We can say with more confidence that we understand why sea level has changed in the past.”

The next IPCC report is expected next year.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.