Global Inflation Prophets Wonder If This Year Is Different

Global Inflation Prophets Wonder If This Year Is Different

(Bloomberg) -- Terms of Trade is a daily newsletter that untangles a world threatened by trade wars. Sign up here.

True believers in the return of global inflation have started 2020 with renewed hope, and the scorn that goes with it.

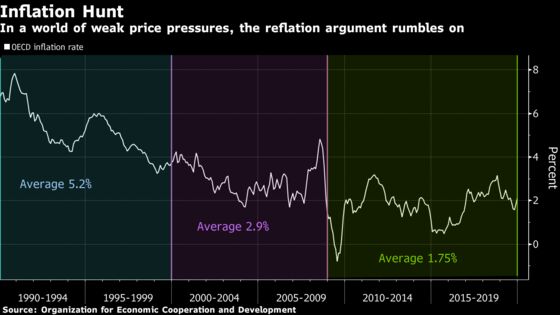

Successive years of paltry price growth, depressed by powerful phenomena from demographic shifts to globalization and technological change, haven’t yet killed the anticipation that the tide will finally turn. When it does, such prophets foretell, central banks will be caught unawares.

Ken Griffin, founder of $30 billion hedge fund Citadel, delivered the latest warning last week, telling the Economic Club of New York that there is “absolutely no preparedness for an inflationary environment” in the U.S.

He’s not alone. Ethan Harris, head of global economic research at BofA Securities Inc., wrote a note in January entitled “Inflation: Talk of Death Greatly Exaggerated” that cautioned against complacency bred by past “false dawns.” Algebris Investments fund manager Alberto Gallo wondered aloud if U.S. or U.K. officials might make a “policy mistake” by keeping monetary policy too loose.

That narrative suggests resurgent inflation spilling over from tight labor markets could leave policy makers scrambling to reverse their ultra-low interest rates and unwind their bond-buying programs.

“If the labor market begins to put ever greater pressure on wages, and supply chains get broken, and productivity slips and you start to see inflation, we have a long way to go for the central banks to correct their monetary policy,” Barclays Plc Chief Executive Officer Jes Staley said in a recent Bloomberg Television interview.

Investors don’t yet see it that way. The bond market’s gauge of inflation expectations, U.S. 10-year breakevens, has had difficulty holding above 2% since early 2019, and is now around 1.66%.

While that’s up from the lows of 2019, it’s still too weak for Federal Reserve officials. Even January’s stronger-than-expected jobs growth gave them to no reason to expect steeper price gains.

“Unless and until we see those low unemployment rates putting excessive upward pressure on inflation, we’re not prepared to say we’re necessarily at full employment,” Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida told Bloomberg Television on Jan. 31.

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say

“The underlying hiring trend is robust, providing a sturdy foundation for domestic growth. However, this is due to be challenged in the relatively near term by weak global growth in general and coronavirus supply-chain disruptions in particular.”

-Carl Riccadonna, Yelena Shulyatyeva and Eliza Winger. Read their U.S. REACT

If anything, Fed officials are more worried that prices will be persistently low. They’re currently reviewing their policy framework, and one idea floating around is a “make-up strategy” in which inflation is allowed to run above the 2% goal for a while to compensate for having fallen short.

Allianz Global Investors fund manager Lucy Macdonald said last month that Britain’s “extremely tight” labor market -- and the prospect of a bumper budget -- stands out as a particularly promising candidate for faster inflation. Yet the Bank of England is unconvinced, with policy makers spending time at their Jan. 30 decision fretting that price pressures are suddenly worryingly weak.

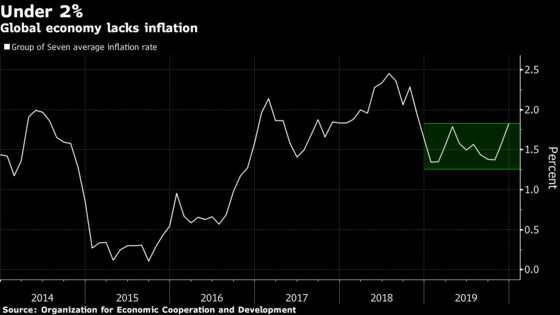

That chimes with the pervading view among Group of Seven central bankers. Average consumer-price gains across the G-7 remained below 2% all through 2019, according to the OECD. It’s confounding for policy makers, who’ve long believed that inflation and employment have an inverse relationship known as the Phillips curve. Tight labor markets, as they currently are, should lift wages and prices.

The European Central Bank renewed its stimulus push last year but, as of last week, President Christine Lagarde was still describing the price outlook as “subdued.”

For Steven Major, HSBC Holdings Plc‘s Global Head of Fixed Income Research, renewed speculation over an inflation resurgence is a movie he’s seen often.

“Why is it, every year, we start with this reflation theme?” he told Bloomberg Television last week. “There is this perennial optimism, somewhat fallacious in my opinion, that gets found out very quickly.”

Fabrizio Pagani, an analyst at Muzinich & Co Inc. in London, is similarly doubtful.

“Particularly with commodities at such a low price, it would be really, really flabbergasting if we have a sudden inflation pickup,” he said in an interview on Tuesday.

But there will be surprises, and exceptions. In China, the coronavirus outbreak sent inflation to an eight-year high last month as transport disruptions boosted food prices. Norway recorded an unexpected price surge in January.

Czech policy makers raised their interest rate last week -- possibly the only increase anywhere so far this year -- to try to bring consumer prices under control. Sweden’s Riksbank engineered an exit from subzero borrowing costs at the end of 2019, deeming inflation there to be strong enough.

Some investors are sticking to their view that faster price growth will return more widely, just not immediately.

“We don’t see inflation in the near term -- we think that globalization and technology are going to keep Phillips curves flat,” said Nicola Mai, a portfolio manager at Pimco. But “because of fiscal activism and central banks really preferring higher inflation to lower inflation, we think over the medium-to-long run, we could have a resurgence.”

--With assistance from Liz Capo McCormick, Francine Lacqua, Anna Edwards, Tom Keene, Matthew Miller and Matthew Boesler.

To contact the reporter on this story: Craig Stirling in Frankfurt at cstirling1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Simon Kennedy at skennedy4@bloomberg.net, Paul Gordon, Fergal O'Brien

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.