Three Countries That Prospered in the ’10s Are in Trouble

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Most developed countries grow at about the same rate, thanks to the broad march of technological progress and globalization. But in each decade, there are a few stars that outperform the rest. Typically, other rich nations look to these winners for clues about how to raise their own growth rates.

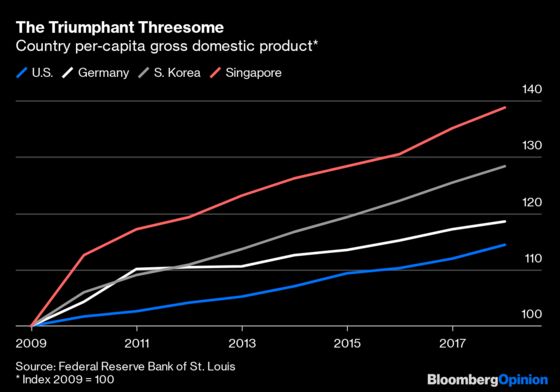

In the decade since the financial crisis, Germany, Singapore and South Korea stand out. All of these countries have outpaced the U.S. since 2009:

For each of these countries, it’s possible to tell a story about why they’ve done so well. Germany’s strong performance is often attributed to its small but productive manufacturing companies, its harmonious relationship between organized labor and management, its vocational education system, and its substantial trade surpluses. Singapore’s success is sometimes credited to its educational prowess, unique public-housing system, and government investment in biotech and other cutting-edge industries. South Korea’s growth, meanwhile, tends to be ascribed to the strength of its national champion companies, especially Samsung Electronics Ltd. Writers, including myself, often recommend that the U.S. copy some of these policies in order to catch up.

But in the past year, these three countries’ economies have begun to look much shakier. Even as U.S. economic numbers look solid, Germany, South Korea and Singapore have all either experienced recessions or come close.

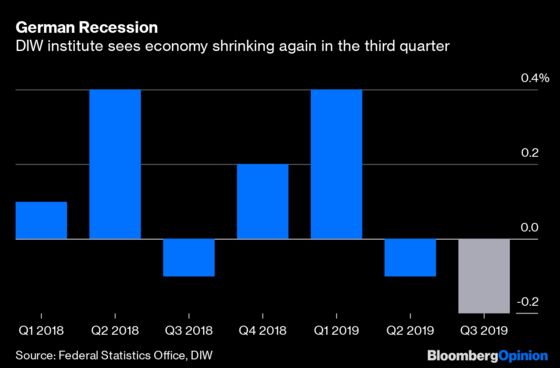

The German economy shrank in this year's second quarter, and it is forecast to contract even more in the third:

A decline in exports is the main cause. About one-eighth of this is due to a slowdown in China, which has been a major customer of German capital equipment and other products. But the whole world is buying less from Germany these days. And where exports go, so goes the rest of the manufacturing sector.

My colleague Chris Bryant believes that a number of trends may be working against the country’s industrial champions. The German automotive industry is highly exposed to climate change, with tightening emissions rules posing a threat to the future of diesel vehicles in particular. A number of European cities are banning diesel vehicles entirely, and some countries in the region have pledged to bar all internal combustion vehicles in the near future.

This shift means a painful adjustment for Germany. The German auto industry represents a huge, deep pool of knowledge over a century in the making; the switch to electric vehicle will quickly make a portion of that knowledge obsolete.

South Korea’s economy grew in the second quarter, but it contracted by 0.4% in the first. Inflation is falling as well, indicating a lack of demand.

As with Germany, exports are the problem, with semiconductors the biggest worry. In recent years, South Korea has become a powerhouse in the industry, as Samsung has eclipsed Intel Corp. as the world’s biggest (and possibly most technologically advanced) semiconductor manufacturer. Semiconductor exports represent about a quarter of South Korea’s entire economy. So a recent drop in shipments – probably due to the China slowdown, the U.S.-China trade dispute, and another brewing trade war between South Korea and Japan – is bound to be painful.

A retreat by Korean consumers could exacerbate the external shock. Households there have taken on a lot of debt in recent years, and a drop in exports could trigger a painful deleveraging.

Singapore, meanwhile, saw its economy shrink in the second quarter. Yet again, falling exports and weakening manufacturing are the culprit. With exports representing more than 170% of gross domestic product, Singapore is one of the most trade-dependent countries in the world, and the U.S.-China trade war – including U.S. restrictions on technology exports – will hit it hard. Ironically, the protests ravaging Hong Kong may help Singapore to avoid a recession in the short term, as financial and business activity shift from the former to the latter. But the longer-term danger of the trade war, combined with an aging population and slowing productivity, will remain.

So all three of these star performers share similar issues – slowing global trade and falling demand for manufacturing imports. The end of China’s rapid catch-up growth, plus the U.S.-China trade war, signals an end to the global economic model that drove growth during the past 20 years. And if the Japan-Korea trade spat signals a more widespread turn toward economic nationalism, the world’s export-dependent economies could be in for even more pain. Meanwhile, the escalating urgency of climate change will disrupt industries like autos that rely on burning fossil fuels.

The economic environment that made Germany, Singapore and South Korea the champions of the 2010s is therefore coming to an end. This doesn’t mean that the U.S. has nothing to learn from these countries’ educational systems, labor relations, and industrial policies; indeed, the U.S. should copy their best elements. But it’s a reminder that different types of economies are suited to different times, and when the times change, the winners and losers change as well.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.