Germany’s Tight Purse Strings Are a Worry When Money Is Free

Germany’s Tight Purse Strings Are a Worry When Borrowing Is Free

(Bloomberg) -- Investors are so keen to find a safe home for their cash that they’re paying the German government to take it, and that makes the nation’s reluctance to borrow increasingly puzzling.

Yields are now below zero for 85% of German sovereign debt, right out to bonds that don’t mature for another 20 years. The government could finance spending for the next decade at an interest rate of less than minus 0.4%, below even the European Central Bank’s record-low policy rate.

Some governments are taking advantage of the ultra-cheap cash -- Austria sold a 100-year bond at just over 1%. Yet Germany, despite a slowing economy that could arguably benefit from a fiscal boost, continues to run a large budget surplus and reduce its already relatively low debt burden.

“The tragedy of this issue is that the government isn’t spending enough on public investment or infrastructure,” Marcel Fratzscher, president of the German Institute for Economic Research in Berlin, said in a Bloomberg Television interview. “My concern is that it’s going to cut expenditures that are urgently needed, thereby weakening economic potential.”

ECB President Mario Draghi has long argued that countries with “fiscal space” -- read Germany -- should use it, and that message won’t dim when he stands down in October. His successor Christine Lagarde, who had greater freedom as head of the International Monetary Fund to make recommendations to governments, told Germany it should lift public spending and cut taxes.

It’s not an isolated trend. Sam Finkelstein, head of macro strategies at Goldman Sachs Asset Management, says there are very few cases where countries are using the low-yield environment to really run rampant fiscal policies. “Are low yields incentivising governments to spend? The answer is absolutely not.”

But most nations are heavily indebted. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s administration ran a record budget surplus in 2018 of 1.7% of GDP, or 58 billion euros ($65 billion), and the debt burden is seen dropping to 51% of GDP in 2023. That’s well within European Union rules requiring a budget deficit below 3% and debt load under 60%.

The European Union’s austerity drive since the regional debt crisis has resonated in Germany more than almost anywhere else. Although Finance Minister Olaf Scholz says the government is investing more than ever, he revised down his spending plans last month. The nation’s twin surpluses -- the budget and the current account -- have been attacked by U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration as unfair.

Financial Plans

A change could benefit the nation, which has no shortage of bridges and transport networks that need upgrading. Factory orders data published Friday highlighted once again that demand for German-made goods is slumping.

In its regular country report this year, the IMF said the digital infrastructure needs overhauling, with only 2.5% of broadband internet connections using fiber-optic cable, more than 20 percentage points below the OECD average.

As Europe’s largest economy, a fiscal expansion should also be positive for the rest of the region by boosting business and consumer spending on European goods.

If there’s a challenge, it’s not the funding of government-led projects but finding the people and producers to do the work, according to Berenberg, a Hamburg-based bank. Unemployment is near a record low.

“There are probably very few public investment projects that are constrained by a lack of money, rather than being constrained by other things,” said Chief Economist Holger Schmieding. “If a good case could be made for investment that could actually be put to use, I wouldn’t be against a modest budget deficit. What I wouldn’t want to see is simply raising public-sector salaries -- once you’ve done it you can never get rid of it.”

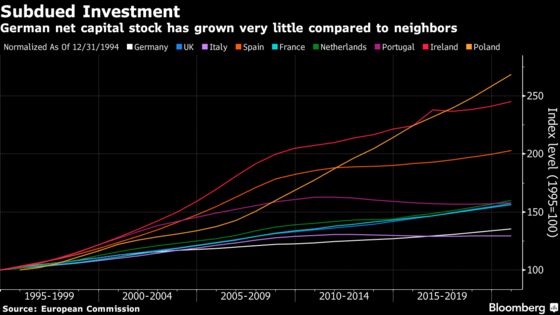

Germany’s strained capacity reflects capital investment that has lagged behind European peers for roughly two decades. More than two-thirds of companies surveyed say they are regularly held back in their business activities by infrastructure deficiencies, according to research by the German Economic Institute in Cologne.

Fratzscher says that current capacity constraints shouldn’t prevent Germany from devising a long-term plan for boosting public investment.

Clemens Fuest, president of the Munich-based Ifo Institute, has another proposal for how to use favorable financing conditions for the public good. The government could issue debt and reinvest into higher-yielding assets, managing a sort of sovereign wealth fund to help finance low-income workers’ pensions.

“One thing the German government needs to consider is whether it makes sense to further bring down government debt when there is so much demand for government bonds,” he told Bloomberg Radio. “This is a weird situation, and something needs to be done about that.”

--With assistance from Anna Edwards and Matthew Miller.

To contact the reporters on this story: Carolynn Look in Frankfurt at clook4@bloomberg.net;John Ainger in London at jainger@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.