From Global Heroes to Rates Near Zero, Rock-Star Economies Flop

Australia and New Zealand now find themselves with just 1 percentage point of conventional monetary policy remaining.

(Bloomberg) -- Their economies were separated by the Tasman Sea and little else: both were geared to the China commodity story and both managed to resist the descent into negative interest rates and bond buying.

How the mighty have fallen.

Australia and New Zealand now find themselves with just 1 percentage point of conventional monetary policy remaining. That’s around the same level the Federal Reserve and Bank of England had when they turned to quantitative easing to support moribund demand following the 2008 financial crisis.

New Zealand’s 50 basis point interest-rate cut Wednesday and Australia’s back-to-back easing in June and July suggest both have joined the global race to the bottom. Policy makers across the world are looking for every bit of stimulus available and currency depreciation is an obvious one.

The kiwi dropped more than a U.S. cent after the RBNZ decision. RBA chief Philip Lowe would have enjoyed the spillover that sent his currency to the lowest level since 2009.

Lowe has noted the trouble with a global easing cycle is that the very nature of exchange rates means not everyone can enjoy the currency benefit usually associated with lower interest rates.

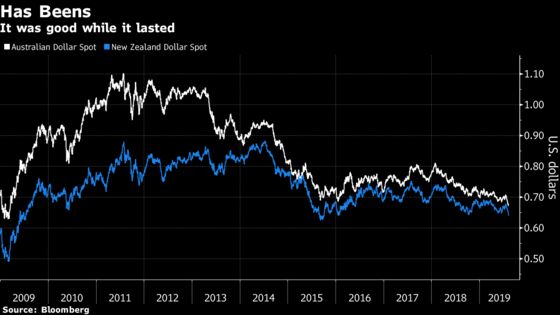

There seems little doubt that Australia and New Zealand’s ascendancy is over and both are now right back in the global policy pack. It’s a far cry from five years ago, when HSBC Plc’s chief economist for Australia Paul Bloxham described New Zealand as a “rock-star economy” and his country’s currency was still near parity with the U.S. dollar.

The Aussie is now trading near the lowest in a decade, buying 67.62 U.S. cents at 9:34 a.m. in Sydney Thursday. Its kiwi cousin has dropped almost 30% from a 2014 peak.

Back to Earth

In hindsight, it was obvious the two economies would eventually fall back to Earth. China couldn’t keep building skyscrapers and railroads to drive its fortunes, meaning demand for iron ore and other minerals was destined to wane. Similarly, while growth in dairy consumption by Chinese households was massive, it was going to have its limits.

As these drivers eased, both economies then switched to riding the housing tiger, leading to property bubbles that eventually needed to be deflated, leaving households creaking under heavy debts with spending constrained.

Finally, as two open, trade-dependent economies with floating exchange rates, Australia and New Zealand are vulnerable to global sentiment -- and while not directly exposed to the U.S.-China economic struggle, both will feel the fallout.

New Zealand’s central bank chief was a little more upfront at his press conference Wednesday than his Australian counterpart has been when it comes to unconventional policy.

“We would be negligent not to be doing the work,” Adrian Orr said, citing how to operate negative rates, conduct asset purchases, run forward guidance as well as other unspecified forms of intervention. “So we are looking at the full tool suite, we’re working very closely with our Treasury colleagues.”

Australia’s governor maintains QE Down Under is unlikely. “I am very hopeful that we will not need to go, certainly into negative territory, or to these very low interest rates that the Federal Reserve and the Bank of Canada got to,” Lowe said in June.

Traders and economists are tending to lean toward the RBNZ’s assessment over the RBA’s.

Lessons Learned

The key question then is, having had time to study and assess the various alternatives used by their northern hemisphere counterparts, whether the island nations have learned from the experiences of the U.S., Europe and Japan, and will do it better.

Australian policy makers reckon they have taken some lessons. One is a multi-pronged approach -- going hard on several fronts at once to try to shock the economy into action.

Both economies have fewer government bonds than major central banks, meaning they wouldn’t need to buy as many to bring down yields. However, most of the action for both is at the short end of the curve and might reduce the effectiveness of QE because in other markets it has been designed to bring down yields on longer-dated securities.

The RBA’s balance sheet can also expand to help reduce upward pressure on funding, as occurred in 2008 when it provided cheap credit to banks. The U.S. experience suggests the RBA would need to buy securities equivalent to 1.5% of GDP to achieve the same effect as a 25 basis point rate cut.

While Australian policy makers had been reticent about negative rates, their assessment from international experience is that they are viable. The concern had been that citizens would pull their money out of the bank and stuff it into their mattresses. But that hasn’t come to pass in nations like Switzerland, Sweden and Japan.

Critically, the floating exchange rates in both Australia and New Zealand remain shock absorbers. They may be doing that job for some time yet.

--With assistance from Tracy Withers and Matthew Brockett.

To contact the reporter on this story: Michael Heath in Sydney at mheath1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nasreen Seria at nseria@bloomberg.net, ;Malcolm Scott at mscott23@bloomberg.net, Chris Bourke

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.