Fraying Relations With China Are About to Hit Australian Economy

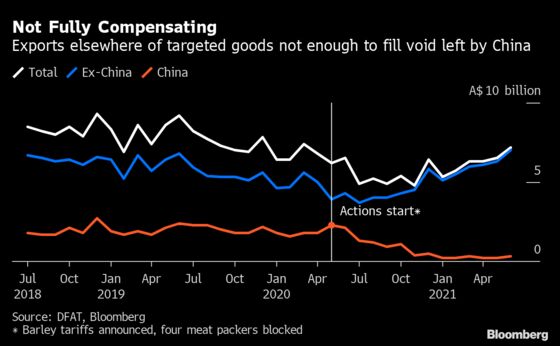

Diversifying trade away from China won’t be easy for Australia.

(Bloomberg) --

Australia’s economic resilience in the wake of China’s efforts to punish it for diplomatic slights has some Down Under declaring victory. They might be speaking too soon.

Former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said last month that China’s campaign to “make us more compliant” has “completely backfired.” Beijing’s pressure, he added, “has demonstrated to China that they can pull all these levers and it doesn’t actually work.”

Exports continue to scale record heights even as China has blocked or limited a growing number of imports from Australian since May 2020. Still, the dispute -- China accuses Australia of taking a hostile approach on issues ranging from a clampdown on foreign investment to questions on the origins of Covid-19 -- is casting a shadow over the future.

Even as Beijing has left the immensely profitable iron ore sector untouched until recently, it’s focusing on Australian products that would form the backbone of future trade, such as lobsters and wine, and warning its students against studying there.

“In the future that’s where the growth will be, all this middle-income stuff, and unfortunately that’s what’s being impacted in this conflict with China,” said Bob Gregory, a professor at Australian National University who has studied the economy for half a century.

It’s a dramatic change from 2014, when President Xi Jinping visited Australia and agreed to sign a free-trade agreement meant to expand Australian exports and bring jobs.

Now the hopes for larger markets and more jobs are in tatters, as tariffs drive up the costs for some goods and Australia’s reputation in China tumbles. The flow of investment has also fallen away, at least partly due to Canberra’s newfound hostility to money from Chinese companies.

Longtime Bonanza

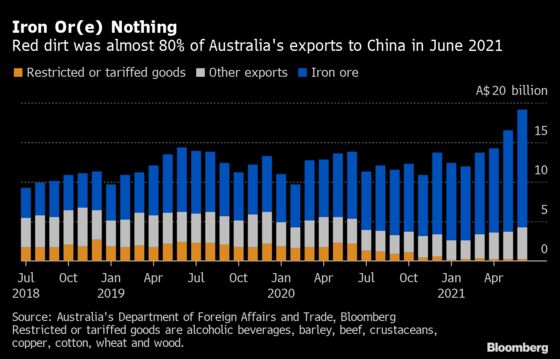

Australia had ridden the China bonanza for nearly two decades, earning windfalls from mineral exports and income gains from cheap imports. That continues for now, with China’s punitive trade actions targeting commodities from coal to barley, lobsters and wine, but leaving iron ore untouched.

Yet while the metal has scaled new heights this year, pushing imports to a record $15.2 billion in July, China is now reining in its steel industry, and the price of iron ore has fallen 39% from a May peak. Demand will likely wane further as China’s economy shifts toward greater emphasis on services, and as Beijing tries to diversify iron-ore supply and cut carbon emissions.

Relations have soured since 2018, when Australia barred Huawei Technologies Co. from building its 5G network, and went into freefall last year as Prime Minister Scott Morrison led calls for an independent probe into the origins of the coronavirus that first emerged in China.

Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Zhao Lijian made clear in July that the trade sanctions were in retaliation for Australia’s actions.

“We will not allow any country to reap benefits from doing business with China while groundlessly accusing and smearing China and undermining China’s core interests,” he said.

Blocking Investment

While at least one major Australian wine producer is trying to ensure that the money spent developing China’s market isn’t wasted, the image of Australian wines has taken a battering.

Chinese tariffs that have made Australian wine more expensive are weighing on demand, but beyond that, there’s also “a lot of people very loyal to the central government’s decisions, so they toe the line,” said Eddie McDougall, an Australian winemaker and importer based in Hong Kong. “People have just lost interest in Australian wine, and very quickly.”

In turn, Canberra has denied rising numbers of Chinese investment and acquisition proposals. Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said earlier this year that he was rejecting investment that would have been approved in the past, arguing that China had changed under Xi.

Chinese investment in Australia tumbled 27% last year to its lowest level since 2007, when the mining boom began, according to a KPMG LLP and University of Sydney report. The government is currently reviewing the 2015 decision to lease Darwin Port to a Chinese company, opening the possibility of retroactively canceling that and other deals.

Outlook

Diversifying trade away from China won’t be easy for Australia. The potential of a limited trade deal with India will provide some hope to exporters, but India is unlikely to fill China’s economic shoes.

Optimists argue that Australia’s relationship with China is bound to improve, citing the experiences of Japan and South Korea: After a rocky patch a decade ago, Beijing came to realize it needed Japanese investment and technology and had limited leverage over Tokyo. And in South Korea struck a compromise deal after a dispute with China over U.S. missile systems deployed in the country.

But Australia’s position is weaker than Japan’s, and neither Canberra nor Beijing have shown a willingness to compromise. China has made clear it’s waiting for Australia to make the first move, while Trade Minister Dan Tehan said Australia is prepared to “pay an economic price” to defend its sovereignty.

Foreign Minister Marise Payne said in August that China has advised that it will only engage in high-level dialogue if Australia meets certain conditions, pointing to a list of 14 grievances China had with Australia that was released last year.

“We can’t meet the conditions,” she said.

That means Australia’s economy, already facing the risk of a double-dip recession as Covid lockdowns shut the nation’s biggest cities, may soon see the trade tailwind fade too.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg