Germany’s Fiscal Paranoia Can’t Compete With Swedish Debt Angst

With the economy now cooling rapidly and the Riksbank all but tapped out, clamor is growing to loosen the purse strings.

(Bloomberg) -- German fiscal frugality is the stuff of legends, but they have nothing on the abstemious Swedes.

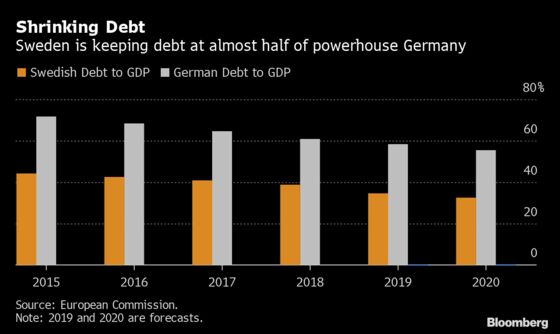

Successive budget surpluses have reduced Sweden’s debt level to the lowest since the late 1970s. This austerity hasn’t made life easy for the central bank, which has held interest rates below zero for close to five years and bought almost half the nation’s bond market to support economic growth.

With the economy now cooling rapidly and the Riksbank all but tapped out, clamor is growing for Finance Minister Magdalena Andersson to loosen the purse strings. A similar debate is unfolding across Europe, with German Chancellor Angela Merkel under pressure to give up on her country’s balanced budget rule.

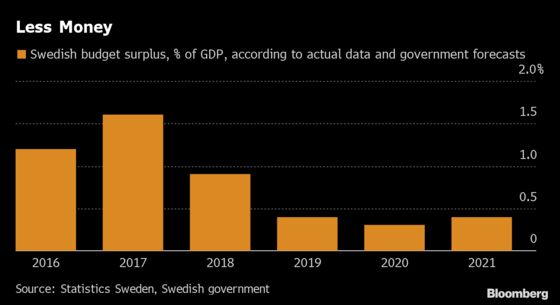

Sweden goes one up on Germany, having its politicians shackled by a surplus target of 0.33% of gross domestic product. The framework is a relic from Sweden’s economic crisis in the 1990s, but is now increasingly being questioned as spending needs mount across the economy, especially at the municipal level.

“This surplus target will drive us into the ditch,” said Asa-Pia Jarliden Bergstrom, an economist at LO, Sweden’s powerful trade union umbrella group.

Some measures have been taken to ease the fiscal straitjacket. The target was lowered from 1% this year and it was also combined with a debt anchor of 35%.

Even so, concerned over coming spending needs, Andersson has been running surpluses that far surpass the target. Debt is predicted to sink through the anchor this year. By contrast, the European Union’s average debt load is more than double the size.

At a presentation of forecasts last month ahead of setting next year’s budget, the finance minister predicted surpluses of 0.4% this year and 0.3% next year. Andersson said that only leaves about 25 billion kronor available for new initiatives given economic and fiscal realities.

Analysts say that far undershoots what’s available and is also foolish given the sagging economic outlook. Especially considering that Swedish bond yields are currently below zero, meaning that the country gets paid to borrow.

“With these extremely low rates -- that are here to stay -- we should discuss what debt levels are appropriate,” said Andreas Wallstrom, an economist at Swedbank AB and one of the loudest advocates for a fiscal push. “Lower rates mean that we can increase debt without it costing more.”

Swedbank estimates that Sweden can run a budget deficit of 50 billion kronor to 70 billion kronor without increasing its debt level. Using this cash would allow the country to boost investments while mitigating a downturn.

Jarliden Bergstrom, the LO economist, also questions the government’s estimates, arguing it can send an additional 30 billion kronor to the municipalities.

“I’m more focused on debt,” she said. “That’s the only parameter of interest when it comes to assessing the health of the public finances.”

Danske Bank A/S chief economist Michael Grahn also said that the real focus now should be the debt anchor. That could free up 70 to 75 billion kronor in spending, given nominal economic growth of 4-5%, he said.

“There’s a risk, of course, that the economy won’t grow next year, and in that case there aren’t any 70 billion kronor to spend obviously,” he said. “But we are close to a situation where we could be more proactive, we could plan for more stimulus instead of just letting automatic stabilizers work.”

But not everyone is ready to jump on the fiscal policy wagon.

The calls for stimulus “ignore history and are naive,” said Torbjorn Isaksson, chief analyst at Nordea Bank AB. “I think we can dismiss that thought. These are very long processes and measures aren’t very effective.”

The finance minister will present her new budget on Sept. 18.

To contact the reporter on this story: Rafaela Lindeberg in Stockholm at rlindeberg@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonas Bergman at jbergman@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.