Food-Price Shock Thwarts Central Banks Fighting Historic Slump

Food-Price Shock Thwarts Central Banks Fighting Historic Slump

(Bloomberg) -- Rising food costs are hitting emerging markets with a double whammy: driving millions into hunger, and thwarting central banks as they try to end the worst slump in decades.

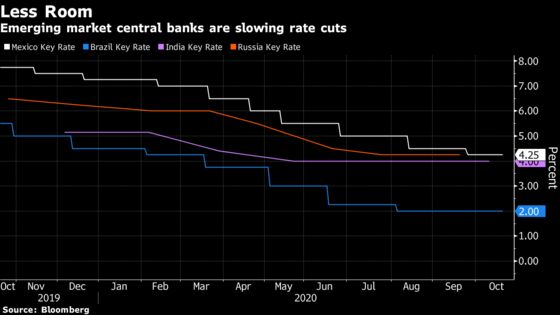

Global food prices have jumped nearly 8% since May as the pandemic disrupts supply lines and dry weather hits harvests. That faster inflation has forced policy makers from India to Mexico to ease up on monetary stimulus just when their economies need it most.

Central bankers at first thought the coronavirus outbreak would have one silver lining: By causing a sharp drop in inflation, it would make room for “very expansive” policy, said Ernesto Revilla, Citigroup Inc.’s head of Latin American economics and former chief economist at Mexico’s Finance Ministry. It didn’t work out like that.

“Mexico is the perfect example of how it became frustrating that you can’t expand monetary policy more because inflation is not coming down as quickly as we would have expected at the beginning,” Revilla said in a phone interview.

Food costs worldwide rose for a fourth straight month in September, led by vegetable oils and cereals such as wheat and maize, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization. Policy makers who had been focused on preventing more bankruptcies and job losses are now also fretting about the jump in prices.

Rising living costs have sparked unrest among people already blighted by unemployment and illness. Authorities imposed a 16-hour curfew in part of Sudan, where bread and vegetable prices drove annual inflation to 212% in September, after protesters blocked major roads. In Pakistan, thousands of civil servants descended on the capital to demand a pay rise to compensate for rising prices.

Since households in poorer countries spend a bigger share of their budgets on feeding themselves, food has a heavier weighting in their inflation indexes. The jump in food costs has helped push some major emerging market central banks to pause or slow interest rate cuts, blunting the main policy tool they have to fight the slump.

Inflation Basket

Hamstrung by above-target price rises, India’s central bank left interest rates unchanged at its last two meetings, even as the economy suffers its worst crash in decades.

Annual inflation quickened to 7.3% last month, the fastest pace since January. Food prices, which make up nearly half of India’s inflation basket, jumped 9.7% from a year earlier.

On the other side of the world, Mexico’s policy makers are in a similar bind. They slowed the pace of interest rate cuts last month, and are mulling a pause to monetary easing amid what looks set to be the deepest slump since the 1930s. Inflation stayed above the upper limit of its target range last month largely due to jump in food prices.

Food costs are pushing inflation rates higher in dozens of other emerging markets, including Brazil, Russia and South Africa. Russia and South Africa hit the brakes recently, while Brazil has signaled it will keep rates at their current record low.

Second-Round Effects

Even if the price swings are temporary, central bankers fear so-called second-round effects, whereby faster price rises cause inflation expectations to go up, which then triggers another round of price spikes.

Local government bonds in developing nations have returned more than 4% over the last four months, according to the Bloomberg Emerging Market Local Sovereign Index. That indicates investors are betting there won’t be a more widespread takeoff in inflation.

“Investors see the phenomenon as temporary,” said Michael Roche, a strategist at Seaport Global Holdings in New York.

A few countries, such as Nigeria and Vietnam, decided to prioritize growth and marched ahead with interest rate cuts despite inflation pressure.

Higher food costs may also delay the recovery by hitting the poorest city-dwellers in the pocket, forcing them to spend less on other goods, said Adriana Dupita, a Brazil-based economist for Bloomberg Economics.

“Food inflation is another headwind for the recovery in consumption and further aggravates income inequality,” she said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.