First-World Refugee Camps in Australia Highlight Climate Fears

For weeks, many of the displaced camped out on sports fields and parks -- unable to access communities cut off by blazes.

(Bloomberg) -- Spilling from burning alpine hamlets and coastal resorts in their thousands, Australians fled raging wildfires towing caravans and trailers packed with pets, livestock and keepsakes.

The exodus was a poignant reminder of how even in one of the world’s most advanced economies, areas can be reduced to the level of disaster zones with refugee camps in the face of a changing climate.

For weeks, many of the displaced camped out on sports fields and parks -- unable to access communities cut off by blazes, or with no homes to return to.

“We have always been aware that we are in a high-risk fire area, and obviously the risk is getting worse,” said Amanda Hopkinson, 48, who fled the settlement of Swan Reach in southeastern Australia on Dec. 30 as fires bore down, then returned, before evacuating again three days later.

She’s keeping a caravan on a sports field in nearby Bairnsdale in case fires force her out again. With the southern hemisphere summer only midway through, that’s a distinct possibility.

“February is when the really hot fire season starts, so no-one will relax until after February,” she said.

Melbourne-based Kon Karapanagiotidis, who has assisted refugees arriving in Australia for about two decades as chief executive officer of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, spent two days helping to prepare meals at a relief camp in Bairnsdale, a city of about 15,000 people on the fringe of a fire-ravaged region in Victoria state.

“At work, every day we see people who are displaced, who are away from families, homes or communities and who are without a safety net,” he said. “It’s really stark and jarring to see that among everyday Australians.”

After five months of blazes, cooler weather has brought some relief to firefighting efforts, though now Australians are facing other natural hazards. Thunderstorms have brought torrential rain and flash floods to parts of Queensland, Western Australia and New South Wales.

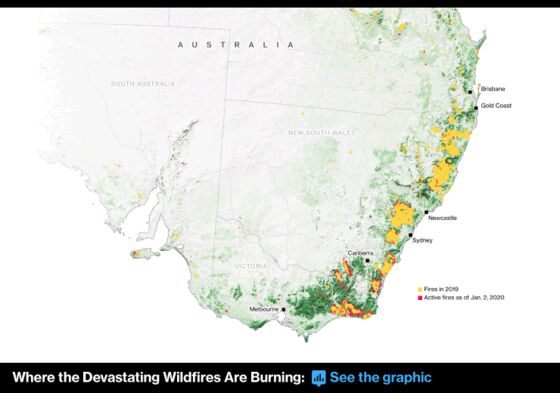

Australia is the world’s driest-inhabited continent and experiences wildfires every year, but the scale of the crisis this season has been extraordinary. At least 28 people have died as flames scorched an area the size of England. The bushfires may have released the equivalent of 900 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the air -- more than the nation’s average emissions for an entire year, according to early estimates from scientists behind the Global Fire Emissions Database.

In the East Gippsland region where Hopkinson lives, state authorities took the unprecedented step before New Year of ordering more than 30,000 tourists to abandon summer vacations and leave the area. That’s drawn parallels with last year’s California blazes that prompted a state-wide emergency and orders for the evacuation of about 200,000 residents.

Dozens of communities in East Gippsland, one of Australia’s worst-hit areas, were fully or partially shuttered during the fires, after power and water supplies were disrupted or access was blocked by charred, fallen trees.

Normally sleepy rural towns became locations for relief workers from organizations such as the Australian Red Cross, who served hot meals and offered support at makeshift camps. The charity has provided assistance at more than 100 relief centers. Some 50,000 people registered with its service to track people who were displaced or at-risk.

Most of the camps have emptied, but local authorities are ready to reopen them if needed before the bushfire season ends in March.

The impact of the fires “is a lesson that dangerous climate change isn’t some far off phenomenon in the future. It is happening now,” said Michael Mann, a professor of atmospheric science and director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University, who is living in Sydney on a sabbatical. “We are in the very best case scenario stuck with this new normal, where these sorts of catastrophic bushfire seasons become a regular occurrence.”

Sharyn Thompson and Kali, her seven-year-old German Shepherd, an accredited therapy dog, were among those helping at the Bairnsdale center. “Before I’d even got Kali out of the car, an older gentleman came over,” said Thompson, from the nearby coastal resort of Loch Sport. “He buried his face into her fur and just cried -- it almost had me in tears too.”

At the peak of the crisis in the week after New Year, hundreds of people camped out in Bairnsdale, with families queuing for hours to get government relief payments. A Sikh voluntary group served up containers of vegetable curries and pasta dishes, while a high-street pharmacy chain distributed health-care supplies from a yellow truck. A mobile veterinary clinic tended to wildlife rescued from ravaged areas, including koalas with singed limbs.

Away from the sports ground, in a tranquil spot on the banks of the Mitchell River, Gaye Dandridge, 58, and her cattle dog Indy spent almost two weeks in a caravan after evacuating the town of Orbost, about 60 miles to the east on Dec. 31.

“I’ve had my moments of crying, feeling lonely and thinking what’s going on?” she said. “Though I’ve spoken to people who’ve had it a lot worse than I have.” Dandridge first attempted to return to Orbost on Jan. 7, only to abandon her plans halfway into the journey after driving into a thick, choking haze. She eventually made it home four days later.

Daryl Parry, 63, is preparing for an extended stay in Bairnsdale after fleeing from Wairewa, a rural enclave about an hour’s drive to the east. “It’s day by day now,” said Parry, standing in front of his modest camp of a small blue tent and white gazebo, his temporary home since Jan 2. “I’m planning to stay here, unless they can find me a place to live.”

There were similar scenes at relief camps in other fire-stricken communities along the south coast of neighboring New South Wales state, including the Bega Showgrounds at the heart of a dairy-producing region blighted by fires.

“Some communities have been surrounded by fires for weeks and months,” said Noel Clement, director of Australian programs at the Australian Red Cross. That’s led to the “trauma of constantly being on alert and constantly being prepared to evacuate.”

Even those who remained in their communities faced challenges, said Julian Poulter, a climate risk consultant and resident in Narooma, a town about five hours drive south of Sydney that’s been threatened by nearby blazes in recent weeks. Days of power outages and dwindling supplies of food and fuel led to “a feeling of societal breakdown,” and had echoes of Hurricane Katrina’s impact in the U.S., he said.

In Bairnsdale, Hopkinson said her community and other rural townships are steeling for more disruptions this summer, and that many accept evacuations are likely to become more commonplace in an era of prolonged droughts and rising temperatures.

“There are too many variables in what is a remote, large area,” she said, rifling through containers for a saucepan. “We don’t have the resources to be able to cope with a disaster on such a big scale.”

--With assistance from Emily Cadman.

To contact the reporter on this story: David Stringer in Melbourne at dstringer3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alexander Kwiatkowski at akwiatkowsk2@bloomberg.net, Edward Johnson, Adam Majendie

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.