Feud Between U.S. Allies Deepens as Trump Sits on Sidelines

During previous national flare-ups, U.S. normally intervened to make sure such grudges don’t spin out of control. Not any more.

(Bloomberg) -- President Donald Trump’s desire to put “America first” has fostered new disputes between the U.S. and its allies. In Asia, old rivalries are also roaring back.

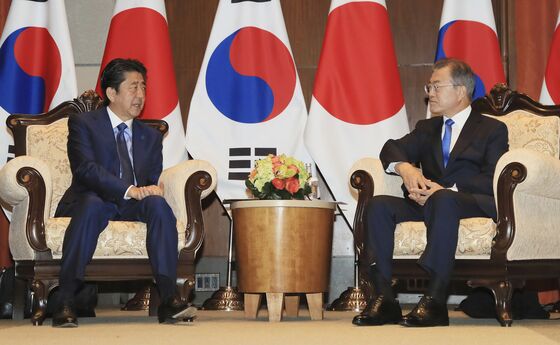

Ties between Japan and South Korea -- two of the U.S.’s closest security partners -- have arguably turned their most hostile in more than half a century over a series of diplomatic disputes. Now, there are signs that the feud, fueled by disagreements over Japan’s colonization of the Korean Peninsula decades ago, is beginning to damage economic and military relations between the neighbors.

During previous nationalistic flare-ups, U.S. administrations normally intervened to make sure such grudges don’t spin out of control. Not any more.

“There’s no leadership from above in the U.S. administration to act in the way we have in the past,” said Daniel Sneider, a lecturer in international policy at Stanford University and author of books on Northeast Asian relations. “At moments like this, it’s been the role of the U.S. to sometimes quietly step in and help to restore communication and sometimes to find solutions.”

The episode in Northeast Asia illustrates how Trump’s skepticism of traditional U.S. alliances and preoccupation with a rolling series of political crises in Washington may be quietly reshaping the postwar geopolitical landscape.

It comes months after Japan capped a restoration of China ties with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe traveling to Beijing, becoming the first premier to pay an official visit to China in seven years. Japan’s ties with its biggest trade partner had turned hostile over disputed islets.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in also warmed to China after he took office in 2017, meeting President Xi Jinping in Beijing to put to rest a spat over Seoul’s deployment of a U.S. missile shield that led to economic retaliation. Xi backed away from punishments imposed by Beijing and Moon promised to pursue a “balanced diplomacy” with Beijing and Washington.

Old Grievances

The U.S. State Department didn’t respond to requests for comment on Thursday and Friday. A second summit planned this month between Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has brought more U.S. attention to the region, with U.S. special envoy Stephen Biegun planning to meet his North Korean counterpart this week.

While ties between Japan and South Korea run deep -- each is the other’s third-largest trading partner -- they’re laden with centuries of grievances, especially Tokyo’s 1910-45 colonization of the peninsula. Disputes over whether Japan has sufficiently atoned for its actions returned to the fore after Moon won the South Korean presidency and pushed back against Abe’s efforts to put the war disputes to rest.

In recent weeks, Japan has reacted angrily to South Korean court efforts to seize assets from companies found to have used forced Korean labor in the colonial era, saying the move violates the 1965 treaty that established relations between the two sides. They’ve also sparred over the issue of women forced to work in Japanese military brothels, with Moon vowing after the death of a “comfort woman” campaigner last week to do everything in his power to “correct the history.”

Military Disputes

Perhaps most consequential to the U.S. is the deteriorating ties between the Japanese and South Korean militaries -- something that could undermine American efforts to counter a rising China. Both defense ministries have accused each other of endangering their personnel after Japan said a South Korean naval vessel used a weapons-targeting radar on one of its military planes in December.

After Japanese Defense Minister Takeshi Iwaya highlighted the radar incident during a visit to the base where the jet was stationed, his South Korean counterpart Jeong Kyeong-doo ordered the navy to “deal sternly” with anymore low-flying planes. Kyodo News and other media have said that defense exchanges are being postponed, increasing the potential for misunderstanding during unplanned encounters.

Domestic Incentive

Neither Abe nor Moon have much domestic incentive to settle, with nationalist sentiments running high. A Nikkei newspaper poll published Monday found 62 percent of Japanese respondents supported a tougher stance against South Korea over the radar incident. That compared with 24 percent who said the Abe government should watch developments cautiously.

“We cannot see where the bottom is,” said Lim Eunjung, an assistant professor at College of International Relations at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, Japan.

Although Tokyo and Seoul have managed to keep their feuding from turning violent over the years, economic risks are growing, including possible Japanese countermeasures against South Korean companies. The number of South Koreans visiting Japan fell 5.5 percent year on year in November to 588,000, according to the Japan National Tourism Organization, even as the overall number of inbound tourists rose 3.1 percent.

Domestic Opposition

In the past, the U.S. has used its leverage as chief security guarantor to keep the rivalry in check, helping to broker their 1965 treaty despite domestic opposition on both sides. Former President Barack Obama’s administration played a key role in getting Tokyo and Seoul to sign a comfort women pact in 2015 and a military-intelligence-sharing agreement in 2016 -- high-water marks for the relationship.

Trump, however, has shown little interest in the alliance since abandoning his military pressure campaign against North Korea last year, focusing instead on U.S. trade deficits and military expenditures with both countries. The U.S. leader skipped a pair of Asian summits in November to focus on the midterm elections and didn’t hold a trilateral meeting with Abe and Moon at the subsequent Group of 20 gathering in Argentina.

Some signs of possible diplomatic efforts by lower-level U.S. officials have emerged in recent days. Ambassador to South Korea Harry Harris visited the defense ministry in Seoul last Monday, while other U.S. officials have emphasized the importance of the three countries working together on North Korea in calls with their Japanese counterparts.

Common Ground

But even on key issues the two countries appear to have little common ground. While South Korea settled its trade negotiations with the U.S. and wants to encourage Trump’s rapprochement with North Korea’s Kim, Japan has yet to start trade talks with the U.S. and favors a more cautious approach with Pyongyang.

“Political leaders on both sides must realize that the damage from deteriorating Japan-South Korea ties fundamentally undermines the U.S. alliance system in East Asia,” said Yuki Tatsumi, co-director of the East Asia Program at the Stimson Center in Washington.

--With assistance from Nick Wadhams.

To contact the reporters on this story: Isabel Reynolds in Tokyo at ireynolds1@bloomberg.net;Youkyung Lee in Seoul at ylee582@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Scott at bscott66@bloomberg.net, Daniel Ten Kate

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.