Fed Will Find It Hard to Talk About Path Ahead After March Hike

Fed officials head toward their January meeting with only tentative conviction that inflation will finish the year below 3%.

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

Federal Reserve officials head toward their January meeting with only tentative conviction that inflation will finish the year below 3% -- as they predict -- and are already saying they may need to raise interest rates faster than expected.

A chorus of officials this month floated raising rates in March and the potential need to hike four and even five times this year. That’s just a few weeks after they forecast three 2022 hikes and the shift will color the debate at their Jan. 25-26 policy gathering.

It also underscores one of their biggest challenges in providing guidance as the pandemic lingers: How to talk about what they are going to do in the future when volatile economic data is causing them to constantly revise their outlook.

“Forward guidance was an expedient tool when they faced low inflation with disinflationary pressures,” said Derek Tang, an economist at LH Meyer/Monetary Policy Analytics in Washington. “It is not clear it is sustainable where risks are bi-directional or tilted to the upside.”

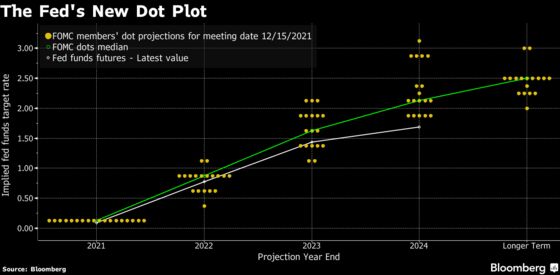

Central bankers over the past two decades abandoned deliberate obfuscation in favor of clarity about their expectations for where they planned to take policy. Former Chair Ben S. Bernanke introduced forecasts and the now famous “dot plot” where all Fed officials actually display their rate outlook.

The goal was to limit the guesswork of investors, which often resulted in needless market volatility. The economy entered the Great Moderation, a period of low inflation and long expansions when it was easier for them to signal what they would do two or three meetings down the road.

Lately, however, surging inflation that drove consumer price gains to a 39-year high of 7% in 2021, and the risk that Covid-19 variants produce more scarcity amid high demand, have caused officials to signal that they might not be that predictable.

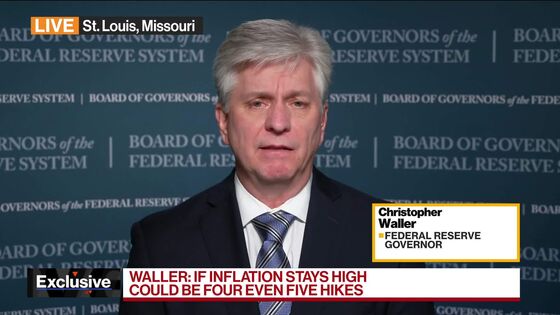

September’s dot plot showed one hike this year. By December that had climbed to three. On Thursday, Fed Governor Christopher Waller said it could take as many as five moves, though it could be fewer if price pressures ease as expected.

“If inflation is just stubbornly high through the first half of this year, we’re going to have to do a lot more,” Waller said in a Bloomberg Television interview.

Others have started to ring the four-hike bell. Patrick Harker, the Philadelphia Fed president who is expected to vote on the policy committee until Boston finds a new president, said he has written down three hikes. “I could be convinced of a fourth if inflation is not getting under control.”

James Bullard of the St. Louis Fed, another 2022 voting member, said four hikes is likely.

Governor Lael Brainard, nominated to be the next vice chair, told lawmakers that she is cautious about the prediction that inflation will slow to 2.5% by the end of the year. “We will simply have to see what the data requires over the course of the year,” she said referring to rate increases.

Current Fed guidance explicitly ties a rate increase to achieving maximum employment. Unemployment fell to 3.9% in December and officials meeting that month thought they were near a fully recovered labor market, according to minutes of the closed-door debate.

The guidance is likely to be retired this month as the Fed prepares to raise rates in March. The formula officials used back in 2015 -- the last time they got ready to liftoff from zero rates -- promised “only gradual” increases. It probably can’t be used again.

Limited Guidance

“What do they say?” said William English, a former senior fed economist who once helped policy makers craft answers to such questions “Given the uncertainties, it would be hard to say they are going to raise rates gradually,” said English, now a professor at the Yale School of Management. “My guess is the guidance will be very limited.”

Central bankers elsewhere are also skeptical of peering too far into the future.

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey said in November that making hard commitments on a rate path is “hazardous in a more uncertain world.”

For the Fed, the task is even more complicated because it will be using two policy tools at once: interest rates and its balance sheet.

Chair Jerome Powell this week said balance-sheet runoff could start later this year. But officials don’t really know how that will impact overall financial conditions. Letting it shrink has the same effect as raising rates -- and could mean they’ll have to hike less than otherwise -- but it’s hard to be precise.

Bill Nelson, chief economist at the Bank Policy Institute in Washington, said part of the problem with Fed guidance is that it was never built for current conditions. The Fed retooled its signal to markets in August 2020 saying it wouldn’t hike until inflation overshot its 2% target and the economy was at full employment, essentially embedding an inflation bias into policy. That was designed for an era when inflation was too low but now they face the opposite problem.

If Fed officials can’t get a grip on inflation, they have to slow the economy: “They say they have the tools, but there is really only one tool and that is to push the unemployment rate up. Nobody wants to talk about that,” Nelson said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.