The Fed Takes a Second Look at Its Good-News Story on American Jobs

Fed’s policy rethink--that began as an inquest in what went wrong--may be widening to include what they got right.

(Bloomberg) -- It began as an inquest into what went wrong. Now the Federal Reserve’s policy rethink may be widening to include the part the central bank thought it had gotten right.

Inflation keeps falling short of the Fed’s target, and that was the trigger for what’s supposed to be a months-long review of strategy. Now, policy makers are being drawn into a conversation about the full-employment side of their mandate too.

The record there looks impressive, with jobless rates near a half-century low. But Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida is hinting at another side of the story, one which may bolster the case against further monetary tightening.

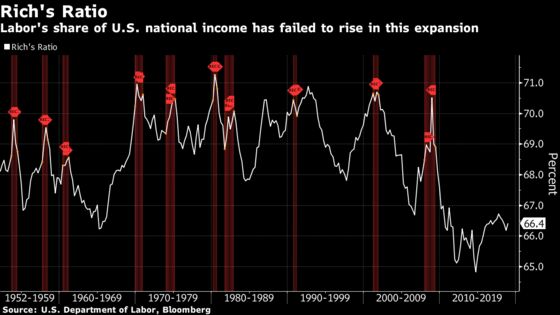

At a Minneapolis Fed conference on April 9, panelists were discussing the connection between monetary policy and the portion of national income that goes to wage-earners -- the so-called labor share. A measure Clarida devised before joining the central bank last year indicates the labor share has yet to rebound after spending much of the current expansion at the lowest levels in many decades.

“I’ve been thinking for several years about this,’’ he commented from the audience during the question-and-answer portion of the presentation. “I hadn’t seen a lot of macro work. So I’m really delighted that folks are thinking about it now.’’

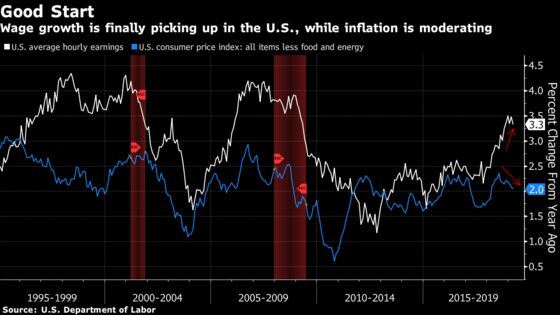

In recent expansions, when labor markets tightened and wage growth accelerated, the outcome wasn’t higher inflation. Workers managed to claw back at least some of their lost slice of the pie, but businesses didn’t pass the higher payroll costs on to consumers. Clarida asked a panelist if his model addressed this. The answer was no.

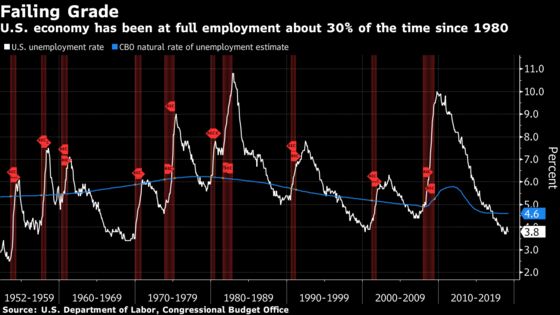

For decades, the Fed’s interest-rate policy has been guided by the belief that pushing unemployment below its so-called “natural’’ level is inflationary. The theory was worked out by conservative economist Milton Friedman in the 1960s, and gained widespread acceptance in the high-inflation decade that followed.

Acting on that logic, Fed officials tightened policy from 2015 to 2018, as unemployment fell toward and then below their estimates of the natural rate. But inflation didn’t pick up as the models predicted it would.

‘Insufficient Vigilance’

Hence the current review -- largely focused on how to influence public expectations about prices. But critics are also asking whether central bankers have simply been too quick to sacrifice further job gains, and not just in the current expansion, but for decades.

“There has been insufficient vigilance in fighting unemployment since the late 1970s,’’ Josh Bivens, director of research at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, argued at the Minneapolis Fed conference. He said the “natural rate” framework was at least partly to blame.

In the period from 1949 to 1979, before that idea took a firm hold at the central bank, the U.S. economy was at full employment two thirds of the time, according to Congressional Budget Office estimates. The ratio has dropped to one third since 1980.

It wasn’t the first time this year that Clarida had raised the connection between the labor share and inflation during Q&A from his seat in a conference audience. He did the same in New York in February. The approach may offer Fed officials a new way of thinking about their maximum employment and price stability goals -– one with an unlikely affinity to Marxian economics.

That’s because it frames inflationary processes at least in part as an outcome of class conflict. It suggests that whether low unemployment automatically translates to higher inflation, as Friedman believed, depends crucially on the balance of power between employers and workers.

Within the past year, growth in pay has accelerated while consumer price inflation has slowed. That suggests workers may finally be regaining some lost ground. But profit margins haven’t come down much, so in Clarida’s framework, there may still be plenty of room to absorb higher wage bills without raising prices -- as in previous expansions -- which would add to arguments against further rate hikes.

When it was his turn to take questions at the Minneapolis conference, Clarida said the point of such events is for the Fed to hear a “different perspective on what full employment means’’ from people of differing backgrounds.

Two days later his colleague, New York Fed President John Williams, echoed the sentiment while speaking at a community development conference in New York. He told reporters afterward that the Fed has at times been too reliant on estimates of the natural rate in defining full employment.

Instead of “trying to pin it to one specific metric,’’ he said, “we really need to think: How could we do that better?’’

To contact the reporter on this story: Matthew Boesler in New York at mboesler1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Ben Holland, Robert Jameson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.