Fed Superstars Lay Out a Map for the Central Bank’s Big Rethink

Federal Reserve officials will face the next recession with limited ammunition.

(Bloomberg) -- Federal Reserve officials will face the next recession with limited ammunition. Their ongoing search for backup firepower could shape the future of American central banking.

After years of careful hiking, officials have raised the fed funds rate to a 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent range. Even if policy makers manage to lift it a few more times before the next recession, they’ll have less room to cut borrowing costs to stimulate growth and stabilize inflation than in the past. This reality is probably the new normal, studies suggest, thanks to demographics and other long-running trends.

Against that backdrop, officials plan to spend 2019 vetting their monetary policy approach, which will likely include figuring out what strategies work best in a low-rate world. Research from the profession’s top brass hints at what might be on the agenda.

The Fed could weigh a new inflation framework or debate tried-and-true policy weapons like quantitative easing, based on policy maker speeches and system research. They might even consider adding options recently used in other economies but untested stateside, like yield curve control -- a topic Vice Chairman Richard Clarida was advising graduate students on just last year.

Below, you’ll find a run-down of potential policy reinforcements and what relevant studies tell us about their efficacy.

(You’re reading Bloomberg’s weekly economic research roundup.)

Temporary Price-Level Targeting

Before delving into solutions, it’s worth reviewing why low rates can cause a snowballing problem for the Fed.

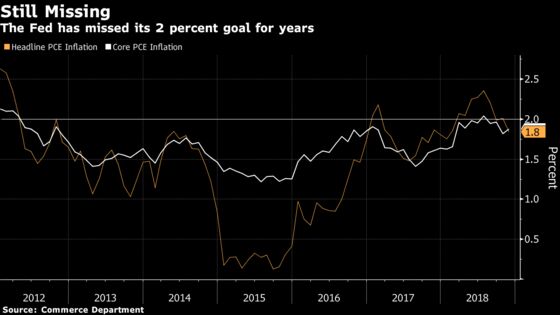

When the policy rate falls to zero, the Fed has less power to coax the economy back from the brink. A long period of below-capacity growth can lead to weak inflation, which can eventually lower business and consumer expectations of future price increases. Expectations are a big determinant of future inflation, so the dimming outlook can mire price gains below the Fed’s 2 percent target even once the economy has recovered. To complete the perverse circle, tepid inflation means the fed funds rate has less room to rise before it restricts growth, leaving the Fed with even less ammunition to fight the next crisis.

Bad news, right? Fortunately, Ben Bernanke has a fix. The former Fed Chair suggested in a 2017 paper that a temporary price-level target might help.

The Fed currently targets 2 percent inflation with a “bygones” approach: officials don’t care how much they’ve previously missed or overshot their goal. They just want to hit 2 percent now. Under a price-level target, that would change. The Fed would try to keep the level of prices going up steadily over time, so a period of too-low prices would require an offsetting period of too-high prices. In effect, that would call for leaving the policy rate lower for longer than a more traditional monetary policy rule might dictate.

People would believe that the Fed was willing to leave rates on hold, the idea goes, so growth and inflation wouldn’t drop as much, and voilà. Crisis averted.

Bernanke suggested using the system only when rates were at zero -- hence the "temporary." That way, the Fed wouldn’t be forced to tighten policy in good times to reverse elevated inflation caused by transitory factors, like a bump in gas prices.

Price level targeting does lead to better outcomes than the current symmetrical inflation target, Bernanke and two top Fed economists -- Michael Kiley and John Roberts -- found in a recent paper. The policies perform best in simulations when the look-back period (the period of time over which you want to hit 2 percent on average) is short, say one year. But their cousin, shadow rate rules, perform even more impressively.

Shadow Rates

They may sound like the film-noir version of central banking, but shadow-rate policies are pretty straightforward. Officials keep track of how much extra accommodation they would have provided if they could’ve only cut rates below zero, then keep rates on hold for longer make up for that missed easing.

Now-New York Fed President John Williams co-authored a version back in 2000 that performs well in Bernanke’s paper, but a newer version by Kiley and Roberts can do better at keeping inflation stable at 2 percent and reducing growth shortfalls.

Bernanke and crew make it clear that their paper is not the final word. What they feed into the model plays a big role in determining the results, and goals may differ. Plus, simpler policies might be easier to explain to the general public -- and better communication leads to better outcomes.

Average Inflation Targeting

If easy-to-convey is key, average inflation targeting is an attractive alternative. It’s price level targeting’s less-dramatic baby sister: instead of shooting for an average level, it calls for an average inflation rate over the economic cycle.

Williams and San Francisco Fed’s Thomas Mertens find that allowing the inflation rate to overshoot 2 percent when policy rates are above zero would help to keep inflation expectations anchored, according to a January paper.

Quantitative Easing

The preceding approaches are variations on the same theme: they leave the fed funds rate lower for longer after a severe recession. But Fed officials are also thinking about what’s in their crisis toolkit beyond rate cuts.

The obvious candidate is quantitative easing, which policy makers turned to three times in the aftermath of the last recession. Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues have made it very clear that bond-buying is still in the Fed’s crisis toolkit.

Still, there are questions. Should bond-buying start only when there are no other options, or does it make sense to use it earlier in a downturn? Kiley finds in a 2018 paper that buying bonds helps most when the strategy is “is deployed promptly when output falls below potential,” but also writes that it’s fine if the policy is secondary -- rolled out only after the fed funds rate has fallen to zero.

“You could imagine executing policy with your interest rate as your primary tool, and the balance sheet as a secondary tool but one that you would use more readily,” San Francisco Fed chief Mary Daly told reporters on Feb. 8. “That’s not decided yet, but it’s part of what we’re discussing now.”

Negative Rates

Big bond purchases aren’t the only non-traditional option available to the Fed. Technically, the central bank could also try cutting rates into negative territory. Other central banks have done so, but by the time Europe tried out the policy in 2014, America’s expansion was well underway.

A few big risks could dissuade the U.S. central bank from pursuing that route. Crucially, the jury is out on how well negative rates have worked abroad -- a recent paper by Brown University’s Gauti Eggertsson actually suggests they can become counterproductive by reducing bank profits. That said, a paper this year by San Francisco Fed’s Vasco Cúrdia makes the case that negative rates could have made America’s last recession less severe while speeding up the recovery, so it’s possible that the topic is still on the table for debate.

Yield Curve Control

Another option the Fed could take for an intellectual whirl? Yield curve control, a policy the Bank of Japan has embraced. Under such a policy, a central bank can control short-term and long-term interest rates through market operations.

The Fed has actually tried out yield curve control before, including during World War II. At the time, the Treasury and Federal Reserve Board used a framework that set caps on long-term and short-term bond yields to stabilize bond markets and curb war financing costs.

Masayoshi Amamiya, Bank of Japan deputy governor, argued in 2017 that the newer version differs from that earlier episode, since it’s deployed as a novel deflation-fighting tool and not a route toward government cost reduction. And a Columbia University capstone project published last year -- advised by now-Fed Vice Chair Clarida -- argued that a modern Fed-sponsored program could provide stimulus even when the fed funds rate had reached zero by reducing the level and volatility of rates, though it would risk growing the Fed’s balance sheet and could be hard to communicate and implement.

“The main appeal” of a Fed-sponsored program “lies in its ability to complement quantitative easing,” the authors concluded.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeanna Smialek in New York at jsmialek1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Robert Jameson, Alister Bull

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.