Fed Seems Resigned to Bubble Risk in Effort to Extend Expansion

Jerome Powell publicly pointed out that the last two expansions ended not in a burst of inflation, but in financial froth.

(Bloomberg) -- Go inside the global economy with Stephanie Flanders in her new podcast, Stephanomics. Subscribe via Pocket Cast or iTunes.

Some Federal Reserve policy makers seem resigned to running a heightened risk of asset bubbles and other financial excesses as they seek to keep the economic expansion going.

That’s one of the messages tucked inside the minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee’s March 19-20 policy making meeting.

“A few participants observed that the appropriate path for policy, insofar as it implied lower interest rates for longer periods of time, could lead to greater financial stability risks,’’ according to the minutes, published April 10.

Chairman Jerome Powell could be one of those officials. He’s publicly pointed out that the last two expansions ended not in a burst of inflation, but in financial froth, first a dot-com stock market boom, then a housing bubble.

A willingness by the Fed to court such perils by holding rates down should be good for the economy for a while. After all, the aim of such a policy would be to sustain growth at a healthy enough clip to meet the Fed’s twin goals of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation.

But that monetary stance could store up trouble down the road should the financial threats materialize.

“Easy financial conditions today are good news for downside risks in the short-term but they’re bad news in the medium term,” senior International Monetary Fund official Tobias Adrian told a Boston Fed conference last year.

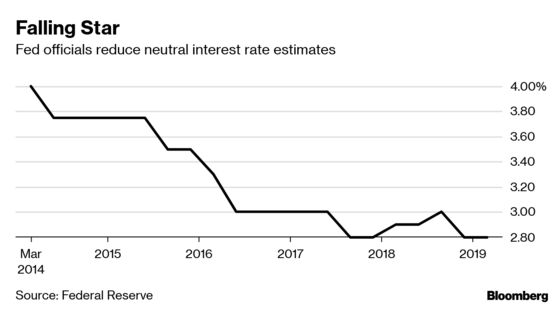

In economists’ parlance, here’s the Fed’s dilemma: R-star -- the neutral interest rate that stabilizes the economy when it’s meeting the Fed’s goals -- may be so low that it also prompts super-risky behavior by investors.

Behind the fall in R-star: an aging population and slower productivity growth that has boosted savings and depressed investment.

In an article last August, Bloomberg coined the term “Fast-star’’ for the interest rate that’s consistent with ensuring “FinAncial STability.’’ A rate too far below that level leads to excesses in the financial system. A setting much above it stifles risk-taking and obliterates the “animal spirits” that drive economic growth.

The trouble is that Fast-star may be higher than R-star, as suggested by the minutes

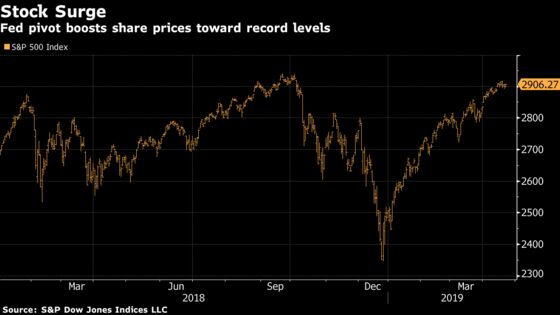

The Fed has put policy on hold this year after lifting short-term rates to 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent in December, within the range it considers neutral for the economy. The dovish shift helped ignite a huge rally in the stock market, with the S&P 500 Index up 16 percent in 2019.

But it failed to satisfy President Donald Trump, who’s vociferously complained that the Fed’s rate increases have held back the economy and the stock market and who’s urged the central bank to open up the monetary spigots to boost both.

A couple of policy makers at last month’s FOMC meeting said that any financial stability risks arising from low rates could be addressed by counter-cyclical macro-prudential policy tools and other regulatory and supervisory measures, according to the minutes.

The problem is that the U.S. has a limited set of such tools, as Fed Vice Chairman for Supervision Randal Quarles acknowledged in a March 29 speech in New York.

Powell told reporters after the FOMC meeting that the Fed didn’t see a high risk of financial instability at this point.

He added that the Fed mainly seeks to keep the system safe by requiring big banks to hold a lot of capital and to undergo annual stress tests of their operations.

At times last year Fed policy makers sounded open to using higher interest rates to lean against potentially over-exuberant financial markets, said Jonathan Wright, a professor at Johns Hopkins University and a former Fed economist.

Case in point: New York Fed President John Williams said in October that the central bank’s rate increases would help reduce risk-taking in financial markets, though he added that was not their principal purpose.

Backed Off

Such talk has since faded. “There doesn’t seem to be the same idea of having tighter monetary policy so as to lessen the risk of asset bubbles developing,” Wright said.

Perhaps that’s not surprising given the shakeout that occurred in financial markets at the end of last year and Trump’s preoccupation with the performance of stock prices.

The strong bounce-back in markets this year means that financial conditions are still accommodative, though not quite as loose as they were before the end-2018 sell-off, according to the IMF.

“There are reasons for fearing the economic consequences of very low’’ rates, former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers said in an April 15 presentation at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

“These include a greater propensity to asset bubbles’’ and “incentives to substantially increase leverage,’’ the Harvard University professor said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Rich Miller in Washington at rmiller28@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Alister Bull, Sarah McGregor

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.