Fed’s Incoming Voters Skew Hawkish. Biden Picks May Tilt Balance

The Biden administration could tilt the balance with its picks to fill three open seats in the Federal Reserve.

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

On paper, the U.S. central bank’s policy-setting committee is set for a hawkish lean this year as incoming voters in the annual rotation among regional Fed presidents replace some colleagues who’ve typically been more dovish.

The 2022 calculus will be a little though, because the Biden administration could tilt the balance with its picks to fill three open seats.

The incoming voters are Kansas City’s Esther George, Cleveland’s Loretta Mester, St. Louis’s James Bullard and the new president of the Boston Fed, which is in the process of recruiting for the position. In the meantime, Philadelphia’s Patrick Harker will cast Boston’s vote.

They replace Chicago’s Charles Evans, Atlanta’s Raphael Bostic, Richmond’s Thomas Barkin and San Francisco’s Mary Daly. Bullard, Mester and George have all made hawkish comments recently about steeply rising prices.

Still, the bigger question is who will fill three vacancies on the Fed’s Board of Governors. The White House on Dec. 17 said President Joe Biden plans to name his selections by the end of the year. It has declined to provide any update on timing since then.

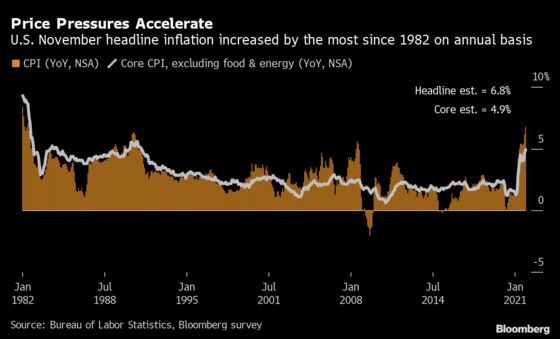

Whoever he selects will have to balance their views on the appropriate policy approach between getting as many people back into work as possible as the economy continues to adjust to Covid-19, with the threat posed by the hottest inflation in a generation.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“Biden’s choices to fill three open Federal Reserve board seats -- expected to be announced soon -- will likely tilt the FOMC toward two rate hikes in 2023 from three as currently projected.”

-- Anna Wong, chief U.S. economist

To read the full note, click here

Jerome Powell, nominated by Biden to another four years as Fed chair, has already led his colleagues in a hawkish pivot by bringing forward the completion of their asset-purchase program to March.

That clears the path for interest-rate increases as soon as the Fed’s March 15-16 policy meeting, Governor Christopher Waller said on Dec. 17, albeit with the caveat that the omicron variant could call his outlook into question.

He was only speaking for himself, but Waller’s clearly not alone in getting anxious about overheated prices.

Some of the incoming voters have already sounded the alarm on inflation. Bullard and Mester both spoke in favor of speeding up the removal of policy support before the Fed acted at its December meeting. Bullard also said officials should be “nimble” when asked if their March gathering ought be live for interest-rate increases. George was warning about high inflation back in November and has a track record of being on the hawkish wing at the central bank.

Outgoing 2021 voter Daly, usually an outspoken advocate for patience in tightening policy to get as many people back into work as possible, also took a hawkish turn in December, declaring that two or three interest-rate hikes could be needed in 2022.

As recently as September she’d been unsure about the need to hike at all in the coming year, when forecasts showed that the Fed’s policy makers were evenly split on the timing of interest-rate liftoff between 2022 or 2023.

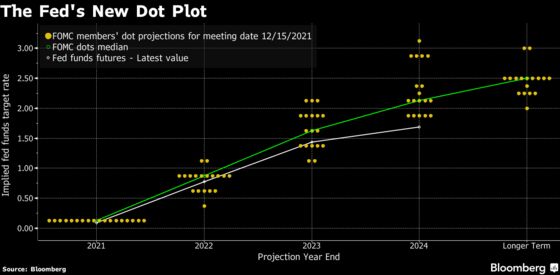

That changed sharply, with the median estimate of Fed forecasts submitted at its Dec. 14-15 policy meeting shifting to three moves next year followed by three more in 2023, after consumer prices accelerated at the fastest annual pace in almost 40 years.

The Fed has 19 policy makers when all seven seats of its board in Washington are filled. Those officials have permanent votes on the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee, as does the head of the New York Fed. The other presidents of the U.S. central bank’s 12 regional branches share FOMC votes on an annually rotating basis.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.