Fed’s Changing Jobs Doctrine Comes to Grips With Racial Inequity

The pandemic and a wave of social unrest have put a spotlight on the deep inequality between black and white America.

(Bloomberg) -- The coronavirus pandemic and a wave of social unrest across the country have put a spotlight on the deep inequality between black and white America. A shift in focus at the U.S. central bank is, too.

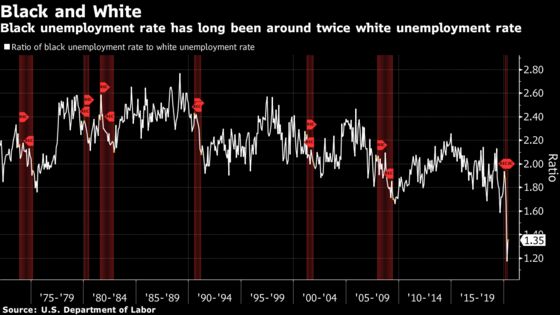

For decades, Federal Reserve policy makers have defined their goal of full employment without much regard to the longstanding gaps between joblessness for white Americans and those for minorities. When they began raising interest rates in 2015 to guard against the possibility of inflation, white unemployment was 4.4%, while black unemployment was 8.5%.

But the price pressures never materialized, prompting Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues to rethink their framework -- including the prospect that labor-market disparities could be narrowed by a more relaxed attitude toward inflation.

On Wednesday afternoon, when they publish their targets for the economy and employment in the coming years for the first time since before the pandemic began, they may reinforce that change in view.

“I worry about it all the time, because if macro policy is going to hold to a hard line, then you’re dooming African-Americans to permanent recession,” said William Spriggs, chief economist of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations. “Fortunately, and very much to Powell’s credit and to Janet Yellen’s credit, they heard complaints from many of us, and they took to heart that that’s not full employment.”

Jobless Rate

Before the U.S. economy shut down, the black unemployment rate was close to a record low relative to white unemployment in nearly 50 years of data. The ratio stood at 1.8 on average in the 12 months through February, reflecting a jobless rate a bit below 6% for black Americans and a bit above 3% for white Americans.

Typically, the gap narrows in economic downturns. But in the early stages of recoveries it usually widens again as white Americans are hired back quicker. Only in the later stages of the last three expansions did black Americans regain ground as private-sector employers faced a shrinking pool of available labor.

Powell acknowledged the way this dynamic had unfolded for low-income communities over the last decade during a virtual event on May 13, when he recalled being urged by community leaders to let the expansion continue to drive down unemployment.

Keep Going

“Their strong advice was: please just keep this going, we’re feeling opportunity we haven’t felt,” Powell said, recounting takeaways from a series of “Fed Listens” events the central bank hosted around the country last year.

“They didn’t feel the first seven or eight years of the expansion, but they began to feel that in years nine, 10 and 11,” he said. “So, it’s particularly painful to see all of that put aside, at least temporarily.”

Powell also stressed that the Fed couldn’t save the economy on its own, and that Congress may need to pass more fiscal aid to ensure a strong recovery.

The pandemic sent unemployment soaring as businesses shuttered to limit contagion. The overall rate stood at 13.3% in May with black unemployment at 16.8% versus a 12.4% rate for white Americans.

Wealth Gap

The U.S. central bank has put a greater focus on racial disparities in economic outcomes in recent years. Economists see a number of reasons for that.

For Rhonda V. Sharpe, president of the Women’s Institute for Science, Equity and Race in Virginia, disparities like the wealth gap between black and white Americans are becoming harder to ignore as the country becomes more diverse and other groups begin to catch up.

According to William Rodgers, a former Labor Department official who is now a professor at Rutgers University, a lot of it has to do with concerted efforts to lobby for Fed appointments who would be more amenable to discussing issues involving race and equity, including Powell’s predecessor, Janet Yellen.

Valerie Wilson at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington points to the proliferation of viral videos on social media highlighting racial inequities -- a factor brought to the foreground amid a wave of social unrest sparked by the May 25 death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police.

“Even though those aren’t explicitly economic issues, I think there’s something about seeing the blatant racism and inequality that continues to persist in this country that serves to elevate people’s consciousness about race, and racial inequality in a number of different aspects,” Wilson said.

Interest Rates

The Fed hasn’t always been so closely attuned to the distributional impacts of its interest-rate decisions, according to David Stein, a University of California, Los Angeles historian who studies American social movements.

“Paul Volcker -- but also the Fed chairs before Volcker -- made choices in making credit so difficult to obtain and raising interest rates so severely that they undermined the life chances and labor market opportunities for the most marginalized workers, and in particular, black workers,” Stein said. “It was the interest-rate hikes that helped produce the 1957-58 recession that catalyzed the March on Washington,” the massive rally that helped push through the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he said.

Andrew Brimmer, the first black American to serve on the Fed’s Board of Governors, compiled reports on the employment situation in the black community during his 1966-1974 tenure. Around that time, civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King were fighting for a federal job guarantee.

Job Creation

Brimmer often pointed to the creation of jobs by the government as a key driver of the labor-market gains for black Americans, warning that “the future of these manpower programs clearly is of major importance to blacks -- as well as to the rest of the country.”

Congress passed the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act in 1978, giving the Fed mandates to pursue full employment and price stability. But the direct job creation efforts supported by those like Brimmer and the Kings disappeared in the early 1980s as President Ronald Reagan sought to shrink government involvement in the economy.

By the end of that decade, the economy had recovered from Volcker’s war on inflation, which had mostly disappeared, but in 1989 black unemployment was at a record high relative to white unemployment.

Now, with overall joblessness at levels not seen since the Great Depression, and black unemployment matching the highest level since the early 1980s, Powell needs to lobby Congress and the White House to once again resume shared responsibility for ensuring full employment, according to Rodgers.

“If we’re really going to get black unemployment rates down, then we are going to need more on the fiscal side,” he said.

Milton Friedman

Since Volcker’s tenure, the Fed has come to lean heavily on a concept known as the natural rate of unemployment, an idea popularized by the conservative economist Milton Friedman, which says trying to push the unemployment rate below its “natural” level will result in runaway inflation.

During the 2007-09 recession, Fed officials ratcheted up their estimates of this natural rate -- assuming the damage to the economy would prevent them from getting unemployment as low as it had been before the downturn -- only to reduce them again when inflation never materialized. They will probably de-emphasize that framework in the future, as Powell acknowledged May 13.

“We’ve learned something very fundamental about our ability to associate levels of unemployment with inflation -- or indeed, other imbalances -- and I think that’s a lesson we’ll be carrying forward,” he said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.