Fed Piles Up $66 Billion in Paper Losses as It Faces Trump Wrath

Mark-to-market losses dwarfed central bank capital at Sept. 30.

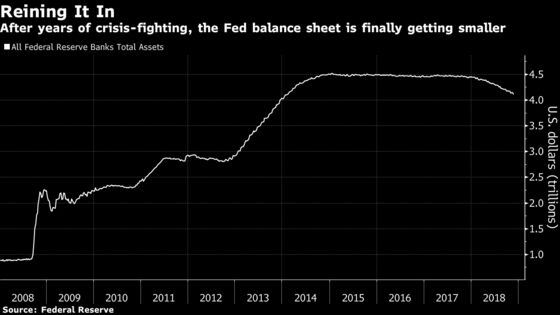

(Bloomberg) -- The Federal Reserve is piling up unrealized losses on its $4.1 trillion bond portfolio, raising questions about its finances at a politically dicey moment for the independent central bank.

The Fed had losses of $66.5 billion on its securities holdings on Sept. 30, if it marked them to market, according to its latest quarterly financial report. That dwarfed its $39.1 billion in capital, effectively leaving it with a negative net worth on that basis, a sure sign of financial frailty if it were an ordinary company.

The Fed, of course, is not a normal bank and does not mark its holdings to market. As a result, officials play down the significance of the theoretical losses and say they won’t affect the ability of what they call “a unique non-profit entity’’ to carry out monetary policy or remit profits to the Treasury Department. Case in point: the Fed handed over $51.6 billion to the Treasury in the first nine months of the year.

The risk though is that any perceived deterioration in the Fed’s finances could dent its standing with Congress and the public when it is already under attack from President Donald Trump as being a bigger problem than trade foe China.

“A central bank with a negative net worth matters not in theory,’’ former Fed Governor Kevin Warsh said in an email. “But in practice, it runs the risk of chipping away at Fed credibility, its most powerful asset.’’

The unrealized losses also provide fuel to critics of the Fed’s huge bond buying programs -- commonly known as quantitative easing -- and the monetary operating framework underpinning them, just as central bankers begin discussing the future of its balance sheet. The ostensible red ink also could make it politically more difficult for the Fed to resume QE if the economy turns down.

“We’re seeing the downside risk of unconventional monetary policy,’’ said Andy Barr, the outgoing chairman of the monetary policy and trade subcommittee of the House Financial Services panel. “The burden should be on them to tell us why this does not compromise their credibility and why the public and Congress should not be concerned about their solvency.’’

Behind the mounting book losses are the Fed interest rate increases that Trump has attacked. They’ve put downward pressure on the prices of the Treasury and mortgage-backed securities that the Fed purchased to aid the economy during and after the financial crisis. The numbers jump around. For example, those losses totaled a less eye-catching $19.6 billion on June 30. They could narrow again this quarter if the recent Treasury market rally holds.

The Fed is currently reducing its bond holdings by a maximum of $50 billion per month -- not by selling them, which could force it to recognize an actual loss -- but by opting not to reinvest some of the proceeds of securities as they mature.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues began in-depth discussions about how far to pare back its portfolio of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities at their meeting last month, the minutes of that gathering show.

That record suggests the central bank likely won’t return to the leaner balance sheet it had pre-crisis and that it may retain its current method of managing monetary policy by paying banks interest on the excess reserves they park at the Fed.

Barr, a Kentucky Republican, has criticized that as a subsidy for the banks. So too in the past has California Democrat Maxine Waters, who will take over as chair of the House Financial Services Committee in January following her party’s victory in the November congressional elections.

In an Aug. 13 note, Fed officials Brian Bonis, Lauren Fiesthumel and Jamie Noonan defended the central bank’s decision not to follow generally accepted accounting principles in valuing its portfolio. Not only is the central bank a unique creature of Congress, it intends to hold its bonds to maturity, they wrote.

Under GAAP, an institution is required to report trading securities and those available for sale at fair or market value, rather than at face value. The Fed reports its balance-sheet holdings at face value.

The Fed annually highlights the amount of profits it hands over to the Treasury: It was $80.2 billion in 2017. The central bank turns a profit on its portfolio because it doesn’t pay interest on one of its biggest liabilities -- $1.7 trillion in currency outstanding.

Congress has limited to $6.8 billion the amount of profits that the Fed can retain to boost its capital. It’s also repeatedly “raided’’ the Fed’s capital to pay for various government programs, including $19 billion in 2015 for spending on highways, Wrightson ICAP LLC chief economist Lou Crandall said.

Then-Fed Chair Janet Yellen opposed the transfer at the time. Tapping the Fed’s resources “impinges on the independence of the central bank,” she told lawmakers on Dec. 3, 2015. “Capital is something that I believe enhances the credibility and confidence in the central bank.”

Given all that, “it would be ironic at this point for Congress to be too upset’’ about the level of the Fed’s capital, said Seth Carpenter, chief U.S. economist at UBS Securities in New York.

Besides, in a pinch, the Fed could operate with negative net worth if it had to, just as other central banks -- in Chile, the Czech Republic and elsewhere -- have done, according to Nathan Sheets, chief economist at PGIM Fixed Income.

That said, parlous Fed finances pose political and communications problems for policy makers.

Warsh, who is a visiting fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, zeroed in on the potential impact on quantitative easing.

“QE works predominantly through its signaling to financial markets,’’ he said. “If Fed credibility is diminished for any reason -- by misunderstanding the state of the economy, under-estimating the power of QE’s unwind or carrying a persistent negative net worth -- QE efficacy is diminished.’’

While a central bank can operate with negative net worth, such a condition could have political consequences, Tobias Adrian, financial markets chief at the International Monetary Fund, said.

“An institution with negative equity is not confidence-instilling,’’ he told a Washington conference on Nov. 15. “The perception might be quite destabilizing at some point.’’

To contact the reporter on this story: Rich Miller in Washington at rmiller28@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Alister Bull

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.