The Fed Doesn't Want Negative Interest Rates Even Though Trump Does

With unemployment near a half-century low, the Fed is a long way from slashing rates to zero or below.

(Bloomberg) --

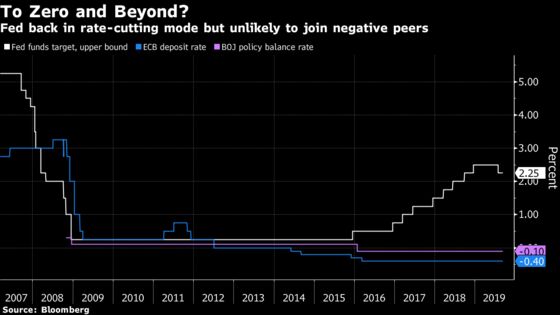

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues are loath to follow Europe and Japan into negative interest rate territory -- no matter what President Donald Trump might want or how bad the U.S. economy might get.

Not only could such a move be deemed illegal, it’s also unclear how much of an economic gain it would yield given the likely disruption it could cause to banks and money market funds.

“I don’t see negative interest rates being a very useful part of our arsenal,” Fed Governor Lael Brainard said in a televised interview with Yahoo Finance in June.

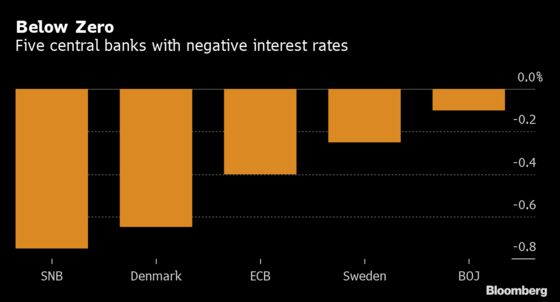

Trump on Wednesday urged the Fed to “get our interest rates down to zero, or less,” arguing in a tweet that the move would allow the U.S. government to bring the cost of servicing its debt “way down.” The tweet came a day before the European Central Bank is expected to cut its deposit rate by 10 basis points to minus 0.5%.

With unemployment near a half-century low and the economy still expanding, the Fed is a long way from slashing rates to zero or below. It is though widely expected to cut rates by a quarter percentage point next week to a range of 1.75% to 2% in response to muted inflation and slowing global growth.

The more pertinent question is whether the Fed would push rates into negative territory if the U.S. economy tumbled into a recession. Based on policy makers’ public and private comments, the answer is probably not.

Bond Buying

Instead, they’d look to other tools -- such as large-scale bond purchases and forward interest-rate guidance -- to try to provide the economy with a needed boost.

Negative rates are “way down the list of things that they would do,” said Johns Hopkins University professor and former Fed economist Jonathan Wright.

The gains are limited, while the political fallout -- Trump to the contrary -- could be large. When the Fed reduced rates to a range of zero to 0.25% in 2008 and kept them there for seven years, it was frequently criticized by lawmakers for short-changing savers.

The Fed studied the possibility of lowering rates below zero in the 2008-2009 financial crisis and its aftermath and found it “wanting,” Vice Chairman Richard Clarida told a Bank of France event in March.

Indeed, in an August 2010 memo, Fed staff members questioned whether the central bank had the legal authority to set negative interest rates in the U.S.

The Fed in 2008 gained authority from Congress to pay commercial banks interest on reserve balances deposited at the central bank. It’s not clear whether that authority extends to establishing negative rates on those reserves.

In the 2010 memo, Fed staffers also raised concerns about the impact that sub-zero rates would have on banks and money market funds.

That’s still a reason for caution in some policy makers’ minds.

“I’m a skeptic about whether that’s a viable option,” Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan said in February when asked about the possibility of lowering rates below zero.

The “big worry” would be “the impact on the financial system and the ability of financial intermediaries to actually be healthy and function,” he said at a Dallas event.

Some economists argue that there’s a limit on how far rates can be pushed down before they perversely start to hurt the economy by prompting profit-pinched banks to curb their lending.

“Negative rates definitely would play havoc with bank profitability,” said Fred Cannon, research director at investment bank Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

Even so, U.S. banks may suffer less than their counterparts in Europe and Japan, he said. That’s because they hold fewer lower-yielding corporate and mortgage loans on their balance sheets.

Money-market funds would also be squeezed by negative rates, though reforms unveiled by the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2014 mean that some are less vulnerable than they were before.

If rates fall below zero, the funds’ first line of defense against investors yanking out their money would be to reduce the fees that the managers charge.

‘Suck It Up’

“If rates don’t go too far negative, the playbook says suck it up and survive on lower fees,” said Peter Crane, president of Crane Data, which tracks money-market funds. “If you go too negative like you see in Europe, then you need another plan.”

The Fed is in the midst of a wide-ranging strategic study of ways it can tackle what Powell has called the “key question” facing it: How can it best manage the ups and downs of the economy in a world of permanently lower interest rates.

But negative rates don’t seem to be high on the agenda. A listing of Fed research relevant to the review on the central bank’s website doesn’t include a section on negative rates, JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief U.S. economist Michael Feroli noted.

What’s more, two of the academic papers presented at a Chicago Fed conference on the review -- including one co-authored by Wright -- cast doubt on how effective they can be.

“Negative rates provide limited stimulus at best,” Notre Dame University professor Jing Cynthia Wu, co-author of the other paper given at the June meeting, said in an email. “At the same time, they could hurt bank profitability.”

--With assistance from Thomas Black and Eddie Spence.

To contact the reporter on this story: Rich Miller in Washington at rmiller28@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Margaret Collins at mcollins45@bloomberg.net, Alister Bull, Scott Lanman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.