The Fed Has Trained Bond Traders Not to Push Yields Up Too Far

Fed Keeps Bond-Market Tantrums at Bay With Stealth Yield Control

(Bloomberg) -- The message from the bond market after the latest brief leap in yields is clear: The Federal Reserve is standing by to prevent an alarming increase in rates, no matter how much debt the Treasury sells amid the pandemic.

Investors have been acting for months as if the Fed has already unleashed one of the remaining tools at its disposal -- yield-curve control, a policy of capping rates to keep them from rising too quickly and squelching an economic rebound. And this week has been no exception.

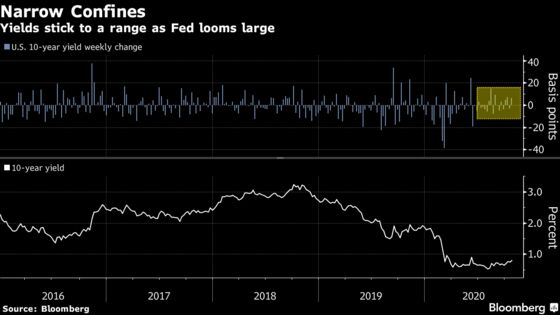

The old adage of “Don’t fight the Fed” is at work here. The mere prospect of central-bank action is keeping yields close to historic lows. In the world’s most important debt market, yields are stuck in a range so tight it has few precedents, even after rates reached a four-month high Wednesday on hints that a U.S. coronavirus-relief package could be taking shape.

Read More: Treasury Yields Rise to Highest Since June on Stimulus Bets

As they have for months, buyers emerged to bat yields back down. The purchasing preserved the sense of calm in fixed income that’s persisted despite the Fed’s August pledge to let the economy run hot to fuel inflation. That episode merely stoked demand as yields climbed toward 1%. These are telling lessons for investors across asset classes, less than two weeks before U.S. elections that could pave the way for an even bigger wave of government spending.

“Yields are almost behaving as if we have yield-curve control already,” said Esty Dwek, head of global market strategy for Natixis Investment Managers, which oversees about $1 billion. “The yield rise will probably remain contained because the Fed is more important than anything else and they will limit it.”

Call it stealth yield-curve control, as Fed policy makers have pushed back on the idea of capping yields. It’s a step that central banks in Australia and Japan have already taken. The Bank of Japan has been pinning 10-year rates at around zero, while the Reserve Bank of Australia targets three-year yields at 0.25%.

In the U.S., yields have been boxed in from both directions. On the upside, the potential for Fed action should the economic picture darken, along with overseas buying and haven demand because of worries about the pandemic, are keeping long-term yields in check. On the downside, the central bank’s reluctance to drive policy rates below zero creates a floor.

Stuck Weathervane

The upshot is that the 10-year Treasury yield, the benchmark for global borrowing and a key weathervane for equity investors, has swung by a mere 23.2 basis points from high to low in September and October. That would be the narrowest two-month range since 2018, and one of the smallest of the past couple decades.

The rate is now at 0.81%, and the options market this week has seen trades targeting yields to stick around current levels for the rest of the year. The consensus on Wall Street is that the 10-year won’t eclipse 1% until 2021.

With speculation building that a Democratic sweep in November could lead to supersized stimulus spending and jolt yields higher, the bond market’s placidity may be a source of comfort for equities investors. There may be less reason to fear a selloff similar to the so-called taper tantrum of 2013, when yields surged after then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke suggested the central bank might scale back its asset purchases.

American taxpayers are also benefiting from low rates. The Treasury is selling record amounts of debt, but it just wrapped up a fiscal year paying the least to service the nation’s obligations since fiscal 2017.

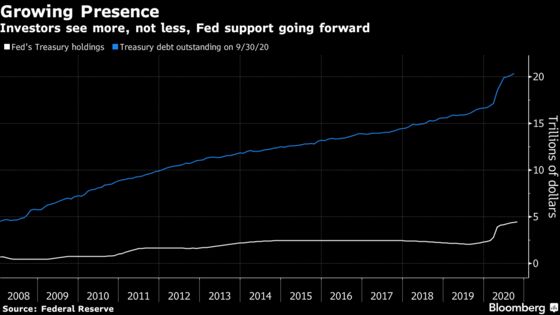

The Fed is still purchasing about $80 billion of Treasuries and at least $40 billion of mortgage securities a month. Policy makers said in September that they would continue buying at least at that pace to “sustain smooth market functioning and help foster accommodative financial conditions, thereby supporting the flow of credit to households and businesses.”

Powell and his colleagues have been pushing for lawmakers to step up with fiscal stimulus, stressing that monetary policy can only do so much to combat the long-lasting effects of the pandemic. Yet if the stalemate in Washington persists, it could lead the Fed to do more.

Minutes of the Fed’s September gathering signaled a readiness to examine the bond-buying program and possibly alter or increase the purchases, on top of keeping policy rates near zero at least through 2023. Officials suggested they might shift some purchases toward longer-term debt to create a bigger downward force on rates. They’ve downplayed the idea of yield caps, but most economists still see it as a possible tool.

Jim Caron at Morgan Stanley Investment Management says he’s “slowly taking advantage” of buying opportunities when 10- or 30-year Treasury yields rise. He predicts the 10-year rate will get no higher than 1.25% and expects the Fed won’t lift rates until at least 2024 or possibly 2025.

“Interest rates are going to be low for an extended time, so that means a limited backup in rates,” he said. “We still own Treasuries and would be happy to buy more if rates rise and overshoot our upside expectations.”

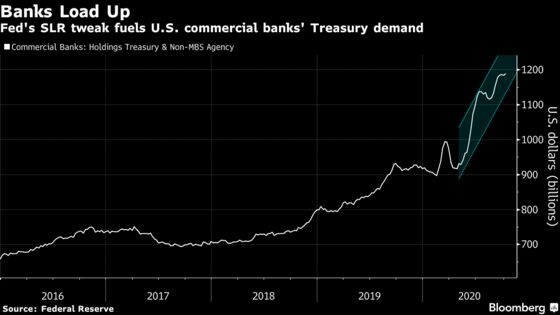

Fed actions have also fostered demand for Treasuries from U.S. banks and foreign investors. U.S. commercial banks have ramped up holdings since the Fed eased some regulatory requirements in April in hopes of reversing a liquidity shortfall.

“If the U.S. recovers more quickly on the back of robust fiscal stimulus, and presumably a vaccine, we could see a move up in yields,” said Alex Etra, a senior strategist Exante Data who formerly worked at the New York Fed. “But if you got a really rapid ramp-up that was at risk of derailing the recovery, that’s certainly a case where the Fed would step in,” he said, noting policy makers’ discussions last month on extending the duration of the Fed’s Treasury portfolio.

“That’s not exactly yield-curve control, but it clearly is intended to reduce the probability that long-term yields rise,” he said.

Any increase in yields should also draw foreign investors, with over $16 trillion of global investment-grade debt yielding less than zero. With hedging costs having cheapened and the U.S. yield curve steepening, the pick-up on 30-year Treasuries for euro-hedged investors is roughly 80 basis points above German bunds.

The Fed’s move this year to bolster currency swap lines has helped make the pricing more attractive for currency hedgers, says Zoltan Pozsar at Credit Suisse Group AG. And while central banks have stepped back from the swaps, the lines still create a backstop to keep hedging costs down.

“There are two policeman that will keep long-end Treasury yields from moving too high: the Fed and the foreign buyers, which can obtain cheap currency hedges through the Fed’s swap lines,” Pozsar said. “It’s Fed policing ultimately, either way.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.