Fed Forecasts to Leave Public Guessing on New Rate-Setting Plan

The Fed’s new approach to setting interest rates will probably be hard to divine from the economic projections.

(Bloomberg) -- The Federal Reserve’s new approach to setting interest rates will probably be hard to divine from the economic projections it’s set to publish on Wednesday.

That’s because those forecasts, released alongside its policy decision, only encapsulate Fed officials’ views about the next few years. The new framework -- which dictates a less-aggressive response to rising inflation than in the past -- likely won’t be put to the test until later on.

The Fed isn’t expected to offer clearer guidance about the conditions it wants to see before raising rates in the statement it releases at 2 p.m. As a result, Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues will be asking the public to believe them when they say that this time will be different, because of their strategy shift.

“The change in the framework really doesn’t come into play until you actually get to full capacity and until you actually get some inflation pressure,” said Aneta Markowska, chief U.S. financial economist at Jefferies in New York. “It’s about how the Fed responds to that. And unfortunately, right now, the projections just don’t extend far enough to capture that.”

The committee slashed its benchmark interest rate to nearly zero at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in March and announced there would be no hikes until the economy was “on track” to meet the Fed’s twin goals for maximum employment and price stability. It’s debated strengthening that guidance in recent months, but Fed-watchers mostly don’t expect that to happen this week because officials have downplayed any sense of urgency in making such a decision in recent public remarks.

New Framework

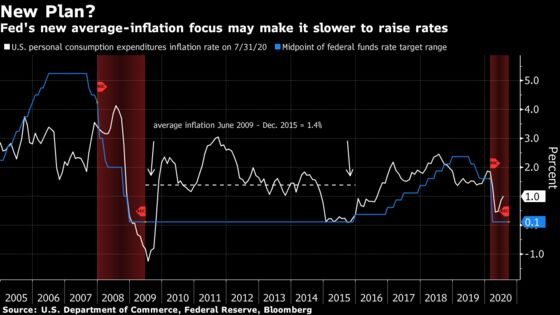

Since March, however, the goals have changed. Powell announced on Aug. 27 that the Fed would now view its inflation target of 2% as something to hit on average over time. That will mean allowing inflation to rise above 2% following periods of below-target inflation -- like the one projected to persist for the next few years, thanks to the blow the pandemic has delivered to economic activity.

The shift leaves open the question of what the new approach means for the timing of future tightening, which in turn has an effect on financial markets. Officials’ economic projections have at times contributed to market turmoil since they were introduced in 2012 because they weight the views of everyone on the committee equally despite their relative influence in the policy debate.

The projections are also compiled in advance of the committee’s policy meetings, which means they don’t incorporate the latest thinking to come out of the meetings themselves. Even so, the Fed chair tends to refer back to the projections in post-meeting press conferences when reporters ask for more clarity on the conditions that will guide future rate decisions.

2023 Dots

When the last set of projections was issued in June, it showed that all but two of the 17 committee participants expected to keep rates near zero through the end of 2022. The projections to be released Wednesday will extend the forecast horizon to the end of 2023.

Economists surveyed by Bloomberg expect the median projection will still show no liftoff in 2023, though they were about evenly split on whether or not the central bank would actually begin raising rates by then. Meanwhile, about three quarters of respondents said they didn’t expect policy makers would be able to declare victory on their new average-inflation target until 2024 or later.

Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida said in an Aug. 31 speech the committee would discuss potential refinements to the format of the projections with the aim of reaching a decision on possible changes by the end of the year. He didn’t say whether that would include extending the forecast horizon.

Andrew Levin, a former Fed economist who assisted Powell’s predecessors, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen, in designing the projections, said that makes the central bank’s job of convincing people it’s serious about its new framework more complicated.

“You’ve got to forecast five and 10 years ahead if you want to talk about average inflation targeting,” Levin, now a professor at Dartmouth College, said. “Professional forecasters think we’re going to be short of the target for the next few years, which really raises the question, what’s the Fed’s longer-run plan?”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.