Fear of Fear Itself Is an Economic Risk as Uncertain 2019 Nears

From Brexit to China, many possible outcomes are up in the air.

(Bloomberg) -- Merriam-Webster announced this week that “justice” was its word of the year. A betting woman might put her money on “uncertainty” for 2019.

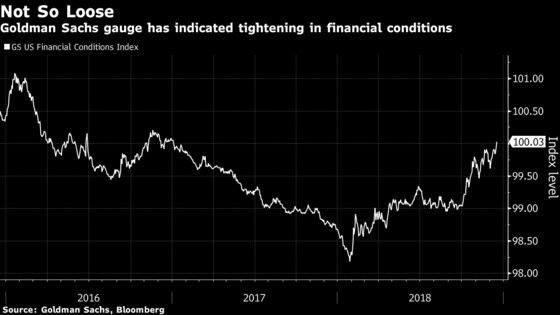

That’s because Brexit negotiations loom large, the U.S. fiscal stimulus may begin fading, in earnest, the extent of Federal Reserve rate hikes is unclear, America’s spat with its major trading partners is unresolved and China’s growth could falter. The yield curve -- which historically signals recessions when short-term interest rates move up above longer-term rates -- is still flirting with such an inversion.

Such fears can be self-fulfilling: the fact that investors and households feel that global growth is on tenterhooks could itself imperil spending and investment, a risk that economists are increasingly alert to as they pencil in their forecasts. Already, a few jittery economic reports have helped to touch off late-2018 stock market volatility.

“There is a growing risk of reverse causation where ‘bad markets create bad fundamentals,’” Ethan Harris, head of global economics at Bank of America, wrote in a note last week. “The problem is that the economy can handle a short period of high policy uncertainty and market volatility, but patience has its limits.”

(You’re reading Bloomberg’s weekly economic research roundup.)

Weakening markets could push U.K. negotiators toward a Brexit deal or encourage Donald Trump’s White House to resolve its trade disputes, but Harris says that as markets come to expect that de-escalation and recover, they’ll take the pressure off. The result, Harris writes, could be “an extended period of waffling.”

Extended uncertainty is economically risky because worries about growth can become self-fulfilling. That idea isn’t new: back in the 1990s, economist Michael Woodford suggested that changed expectations about future growth can slow investment decisions today, which then feeds back into current demand.

Just this month, a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper found that when people are uncertain, they exercise caution in consumption, borrowing and investing. The broader point is that households with less education levels, lower incomes and a more precarious financial situation tend to be less sure of their economic futures and may be particularly reticent as a result.

To be sure, Harris’s base case is that tensions ease on Brexit and trade and this bout of storminess will blow over. Still, as some economic indicators flash warning signals in the U.S. and Europe, and the Federal Reserve adopts a more meeting-by-meeting approach to rate decisions, clouds hang on the horizon.

Also worth a read this week...

Baby boomers’ retirements could cause a 2.8 percentage-point decline in productivity growth between 2020 and 2040, according to this St. Louis Fed working paper. Boomers slowed productivity when they entered the workforce -- accounting for 75 percent of the late-1960s and 25 percent of the early-1970s slowdown -- because they had relatively low skills and earned lower wages. Now they have a lot of on-the-job expertise and high wages, and as they retire, they’ll take those with them. “After 2020, the mean age of workers will decline again, as it declined upon the entry of baby boomers into the labor force throughout the 1960s and 1970s,” Guillaume Vandenbroucke writes.

Developing countries may benefit from automation even though they’re lagging in industrial robot adoption, according to this World Bank research paper. While it seems like robots in industrialized economies could spell trouble for countries -- many specialize in cheap labor, which robots replace -- the use of machines in advanced economies could boost demand for component parts sourced from developing nations, according to the researchers’ model. Plus, by making production cheaper, the advanced-economy shift toward machines leads to more exports to developing economies. As that dual change happens, “real wages and welfare are likely to increase” in the less-developed places, “reflecting also lower consumer prices.”

Google could give economists insight into low-income developing nations: search trends are an effective alternative economic activity indicator for places with shoddy data. Looking at an index of search volume, International Monetary Fund researchers find that when people are searching for country names in various economy-related categories -- including finance and travel -- it can correlate with growth or inflation. In fact, the relationship between Internet search and gross domestic product is stronger for low-income nations than nighttime lights and GDP, a commonly-accepted proxy for economic activity.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeanna Smialek in New York at jsmialek1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Scott Lanman, Jeff Kearns

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.