There’s a Case for Negative Rates in Australia, Ex-RBA Researcher Says

Australian policy makers are yet to make a compelling case against deploying negative interest rates to help revive the economy.

(Bloomberg) --

Australian policy makers are yet to make a compelling case against deploying negative interest rates to help revive the economy, according to Peter Tulip, who until last week was a senior member of the central bank’s economic research department.

“The evidence suggests that negative interest rates work,” said Tulip, now chief economist at the Centre for Independent Studies -- a think tank in Sydney. “Why is the experience of other countries that have successfully used negative interest rates, why is that inapplicable to Australia?”

Reserve Bank of Australia chief Philip Lowe, in testimony Friday, pushed back against the suggestion that a year of negative rates might be better than a decade of the cash rate at zero. The governor said he hadn’t ruled out going negative, but reiterated that it was extremely unlikely.

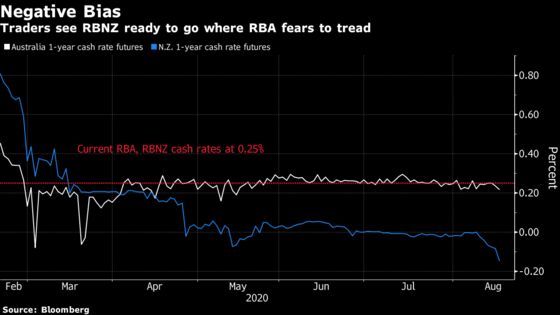

The Australian central bank’s reluctance to take rates negative contrasts with its counterpart across the Tasman Sea, with New Zealand suggesting that it’s prepared to use such such tools if required. Tulip, whose research publications have been regularly cited by Australian lawmakers during the RBA’s semi-annual testimony, notes the contrasting strategies.

“On a spectrum of readiness to entertain new ideas, and that’s closely aligned with interest in academic research, and intellectual fads, the New Zealanders are at one end of the spectrum and we’re at the other end,” he said.

Leaning Against Wind

Tulip’s research shot to prominence last year when he and former colleague Trent Saunders released a discussion paper that found the cost of tighter monetary policy to protect against asset bubbles and associated unemployment were three-to-eight times larger than the benefits.

The paper was driven in part by the reaction to the 2008 financial crisis, when banks collapsed after poor and excessive lending and a view developed that tighter policy could help avoid that repeating.

Indeed, in 2002 Lowe authored a paper with Bank for International Settlements economist Claudio Borio arguing the risk of a financial meltdown greatly increased after long periods of rapid credit growth and surging asset prices. They said central banks should use rates to safeguard financial stability by ensuring bubbles didn’t get out of control.

Tulip, who did nine years at the RBA and a bit longer at the U.S. Federal Reserve in the years prior, acknowledged the governor’s paper had been “very prescient” ahead of 2008, but was now overtaken by subsequent research.

Housing and house prices are one of his key research areas and his final paper before leaving the RBA found apartment buyers in Sydney pay hundreds of thousands of dollars more due to height limits preventing more construction.

As to the housing market’s resilience amid the pandemic -- house prices have fallen just 1.6% from the most recent peak in April -- Tulip said this wasn’t surprising. Buyers tend to look at comparable properties around the area they’re buying, which often sold months or years earlier, slowing the rate of change.

He noted that the cash rate at 0.25% is also at a record low, “so a lot of people are finding it much easier than they used to to buy a house.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.