Europe’s Poster Child of Growth-Friendly Policies Is Rebelling

Europe's Poster Child of Growth-Friendly Policies Is Rebelling

(Bloomberg) -- Explore what’s moving the global economy in the new season of the Stephanomics podcast. Subscribe via Apple Podcast, Spotify or Pocket Cast.

Spain’s image as Europe’s poster child of growth-friendly economic policy is starting to wear a bit thin.

Labor reforms enacted seven years and four governments ago still get cited admiringly by officials in Frankfurt and Brussels as an example for others to follow. But political stasis in the euro zone’s fourth-biggest economy increasingly threatens to leave one of the region’s most dysfunctional labor markets to fester.

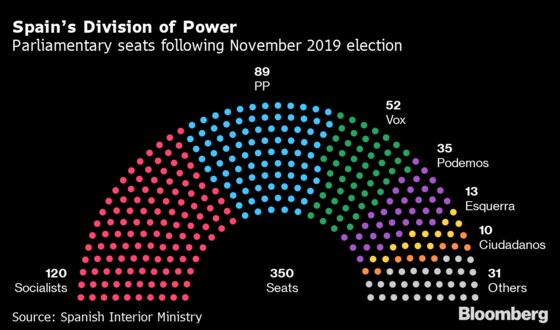

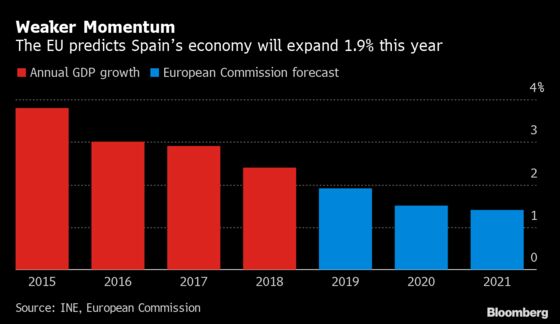

Earlier this month, Spaniards elected a Parliament even more divided than the last one, dashing hopes lawmakers might build on half a decade of robust growth by injecting the economy with more reform adrenaline. While European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde craves a new “policy mix” for the region to boost expansion, Spain risks proving to be her first disappointment.

“Many of the reforms that need to be put in place -- labor market reforms, pensions and education -- they’re very subject to the political cycle,” said Maria Jesus Fernandez Sanchez, an economist at Spain’s Funcas think tank. “They won’t be implemented in the way they need to be. In fact, there’s a real risk that some of the past reforms will be undone.”

Spain’s last major structural changes were in 2012, in the aftermath of the country’s double-dip recession. Those measures included one that made firing workers less expensive and another that gave companies more control over wage negotiations.

The healthy economic expansion that followed elicited applause from policy makers. In February, the European Commission credited those reforms with having made growth more balanced. Former ECB President Mario Draghi and colleagues often singled out Spain with approval too, and Chief Economist Philip Lane did so even last week.

‘Mission Unfinished’

“Take Spain, for example, which has been growing very, very well,” he told Italian newspaper La Repubblica. “There’s a strong consensus that some of the policies they adopted in terms of reforming, for example, the labor market, have helped.”

Spain may also typify what Lagarde identified in her September testimony to the European Parliament as an example of “mission unfinished” on structural policies.

“There haven’t been reforms for seven years,” said Toni Roldan, a former lawmaker with the centrist Ciudadanos party, now the director for the Center for Economic Policy and Political Economy at Spain’s ESADE University. “It’s a major lost opportunity.”

That outcome is partly a result of political fragmentation. Three new parties led to an increasingly fractured Parliament, hindering attempts to double down on reforms.

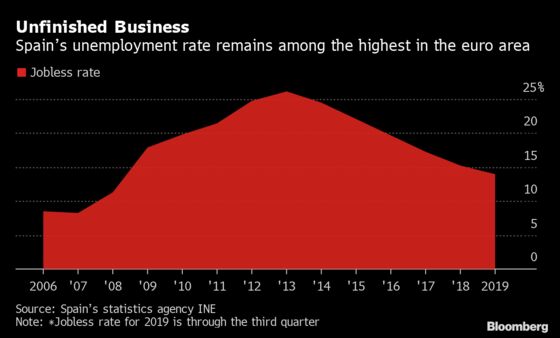

Inaction risks leaving unhealed the ills of an ineffectual education system and the region’s second-highest unemployment rate after Greece, at 14%. Despite unused labor, Spanish businesses complain frequently that they can’t find qualified workers.

The most likely outcome of government talks is a left-wing administration where Socialist Party leader Pedro Sanchez will stay on as prime minister, and anti-establishment party Podemos will hold the deputy premiership. That would create Spain’s first coalition since it returned to democracy four decades ago.

Such a government would probably come up short on measures Lagarde and colleagues might like to see. She cited the need for structural reforms in Europe in her September testimony, while last week she called for “policies to boost internal growth.”

Spain even risks shifting backwards. Podemos wants to overturn the 2012 reforms, including changes that gave companies more control to negotiate contracts at the firm level rather than industry-wide. Many left-leaning lawmakers view the original changes as too drastic and ineffectual, according to Sebastian Royo, a Harvard University visiting scholar.

“The reform went too far in providing flexibility,” he said. “It was at the expense of job security and work stability.”

The center-left Socialists, a more market-friendly party, might shun a full-scale reversal, but could allow some policies to be tweaked.

What Spain should really be doing, according to the commission, is shoring up public pensions, simplifying hiring to encourage full-time job contracts, curbing the high-school dropout rate, and also ensuring schools teach relevant skills and qualifications.

Spain’s status as a role model may reflect a lack of other good examples. Back in 2012, the commission said European Union countries had made “some progress” in adopting 78% of structural reform measures it had called for. Last year, countries made no progress on more than half of its latest recommendations.

The EU still predicts Spain’s economy will expand 1.9% this year, far exceeding the euro zone as a whole. But momentum is decelerating as job growth slows and Brexit uncertainty and trade tensions weigh on companies’ outlooks.

With that backdrop, some people are now unconvinced the original labor-market changes were worth it.

“Is the reform really working?” Royo, the Harvard scholar, said. “If you are on the left, people will tell that it is not.”

| Read more... |

|

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeannette Neumann in Madrid at jneumann25@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Fergal O'Brien at fobrien@bloomberg.net, Craig Stirling, Zoe Schneeweiss

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.