ECB Needs Europe to Spend More — And Gets An Extra Bonus If It Does

ECB Needs Europe to Spend More — And Gets An Extra Bonus If It Does

(Bloomberg) --

When Christine Lagarde calls on governments to aid the euro-zone economy by spending more, the new European Central Bank president has an added incentive.

Convincing countries such as Germany, which runs a budget surplus, to stimulate growth is now a priority for the institution. That would complement the quest to revive inflation -- and at the same time create more bonds for officials to snap up under their quantitative easing program.

Uncertainty over government borrowing is one reason central bankers can’t easily work out how long they have before QE runs into the ECB’s self-imposed limits on how much debt it can buy, according to a euro-area official involved in the discussions speaking on condition of anonymity.

Giving her first speech as ECB chief on Monday night in Berlin -- at an event to honor former German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble, now president of the lower house of parliament -- Lagarde chose not to push the ECB’s request so soon, staying away from policy remarks.

She has a bit of room to wait. Her predecessor Mario Draghi said as his term ended last month that it will be “quite a bit of time” before the problem arises of limits to QE. He also alluded to the lack of visibility though, as estimates of remaining volume in the market are based on assumptions for debt issuance, which are derived from assumptions about public spending.

At his farewell ceremony last week, Draghi said governments and the central bank need “mutually aligned” economic policies -- and the ECB is doing its bit with ultra-low interest rates to encourage politicians to at least temporarily look past their post-crisis focus on debt reduction.

QE “has allowed many governments to have more fiscal space,” Silvia Ardagna, managing director in the investment strategy group at Goldman Sachs Private Wealth Management, said in an interview. “There’s potential for some governments to step in with fiscal stimulus. That’s something we expect Lagarde to push for.”

Lagarde’s diplomatic skills after past careers as French finance minister and IMF head should help. They’ll also be critical in managing relations with her new colleagues. The reactivation of QE in the final week’s of her predecessor’s term provoked opposition from governors in the core of the euro area, most notably Germany, and those arguments haven’t gone away.

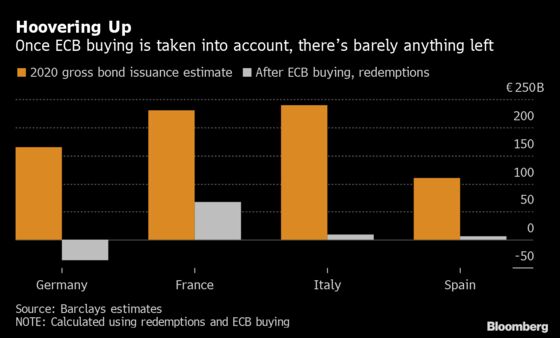

To quell earlier disputes and lawsuits, the ECB promised to buy no more than 33% of any nation’s debt issuance. The aim is to assuage concerns that it’s effectively -- and illegally -- financing governments by printing money.

It’s already at that limit in some nations and could hit it soon in others though. Then it has to decide either to stop buying bonds or change the rule, potentially reigniting the furor. The more debt issued by governments, the more time Lagarde has before the standoff arrives.

Estimates vary for how long QE can run. In Germany, it could be as little as 14 months, according to Danske Bank, while in Finland it may only be until the middle of next year, said Rabobank International strategist Richard McGuire. David Owen, chief euro economist at Jefferies International, reckons the debate can be avoided at least until the ECB’s first forecasting round next year.

“At the moment she doesn’t have to do anything, she just has to wait,” he told Bloomberg Television. “Come March, she’ll have to make fundamental decisions about where we go next, in terms of the program.”

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say...

“The ECB’s current issuer limits already leave several countries without any public-sector bonds (agency, general government as well as local and regional debt) to purchase. And Germany isn’t the only country with a problem.”

- David Powell. See his ECB INSIGHT

Aside from the economic arguments for fiscal stimulus, the ECB’s loose monetary policy is giving leaders a good debt-management reason to issue more debt. Around two thirds of sovereign bonds now have rates below zero, meaning governments are being paid to borrow.

“The real trick for the ECB now is just to keep rates at such low levels that finance ministers say, ‘look we can borrow for a very, very long time, let’s get ahead and do it,”’ Peter Kinsella, Union Bancaire Privee UBP Global Head of FX Strategy, told Bloomberg Television.

Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda offered another perspective on the matter on Tuesday, saying that ultra-low interest rates also amplify the effects of budget stimulus.

“If fiscal policy becomes more aggressive with interest rates at appropriately low levels and continued easing in place under the current yield curve control policy in an overall policy mix, fiscal policy will be more effective,” Kuroda said at a press conference.

In the meantime, Draghi has gifted Lagarde two arguments to deploy that give the ECB substantial flexibility with its rules. One is that a promise to buy bonds in proportion to the size of each euro-zone economy -- for example, it should purchase roughly twice as much German as Spanish debt -- applies only to the total stock of holdings and not to monthly volumes.

Secondly, according to Draghi, previous litigation at the European Court of Justice established that the restrictions depend on the economic circumstances the ECB faces -- circumstances that the central bank itself lays out in its quarterly projections.

“These limits first of all are self-imposed and, second, are specific to the contingency in which they were originally stated,” he told reporters. “The ECJ has granted ample discretionary power to the ECB, within its mandate.”

--With assistance from Nejra Cehic, Jana Randow and Piotr Skolimowski.

To contact the reporters on this story: Craig Stirling in Frankfurt at cstirling1@bloomberg.net;Ksenia Galouchko in London at kgalouchko1@bloomberg.net;John Ainger in London at jainger@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Simon Kennedy at skennedy4@bloomberg.net, Paul Gordon

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.