ECB’s No-Limits Stimulus Isn’t Yet Opening Door to Yield Targets

The European Central Bank insists it’ll stay away from yield curve control.

(Bloomberg) -- When the European Central Bank meets this week to review its radical suite of measures to revive the economy, there’s one tool it insists it’ll stay away from: yield curve control.

The policy of intervening in the market to keep bond yields at a specific level was adopted by the Bank of Japan almost four years ago, and followed by Australia this year amid the coronavirus crisis. The U.S. Federal Reserve is “thinking very hard” about it, policy maker John Williams said in May.

Not so the ECB. Chief Economist Philip Lane said two weeks ago that “we are not, absolutely not, into yield-targeting or yield-curve control.”

Bond yields are at the heart of the debate over how to manage the massive debt loads that countries are building up as they grapple with the coronavirus pandemic. If public authorities can’t find a way to make the burden affordable, their economies could be crippled for years.

Yield curve control tackles that head on by keeping the cost of government borrowing, and by extension the price of credit throughout the economy, manageable for years to come. Unlike central-bank interest rates, which mostly affect very short-term debt, it can influence whatever maturity is considered most appropriate.

The BOJ, for example, aims to keep the nation’s 10-year sovereign bond yield close to zero. The Reserve Bank of Australia is targeting three-year yields around 0.25%.

Lane argued that the only way to ensure particular yields is to promise to buy everything, at least at the maturity being targeted. That’s hard enough in an economy with only one government. The euro zone has 19, and two more on the way, with huge variations in economic and budgetary strength.

“It is more nuanced in a currency zone with multiple fiscal issuers,” said Chris Iggo, chief investment officer for core investments at Axa Investment Managers. “The ECB has to simultaneously manage the yield curve and the sovereign credit spread, but the idea is to keep government bond yields at extremely low levels and stable.”

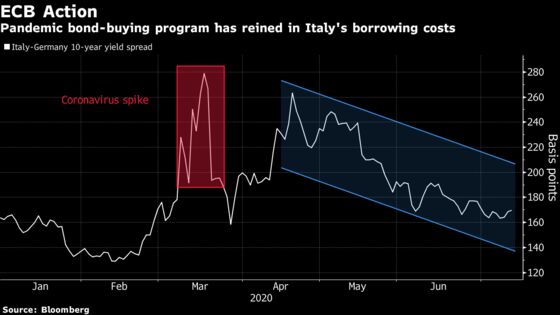

Spreads between different bond yields are a key measure of stress. Thanks to the ECB’s 1.35 trillion-euro ($1.5 trillion) pandemic emergency purchase program, they’ve been narrowing across Europe since the virus-induced market rout in March.

The keenly watched divide between Italy’s 10-year bonds and Germany’s has plunged since rocketing higher four months ago, and now stands at about 170 basis points.

Were the ECB to eradicate that gap completely though, it could credibly be accused of monetary financing of governments, which would be illegal.

Walking Dead

There are other risks with yield curve control. Steven Major, head of fixed income research at HSBC Holdings Plc, says they include the hampering of market functioning, and the survival of so-called zombie companies that would otherwise have failed.

The policy can also be a disincentive to governments to rein in wasteful spending, making it hard for the central bank to disentangle itself later.

“The threat to central bank independence becomes greater when the balance sheet is increasingly seen to be consolidated with the government,” Major wrote. “Both government and central banks become aligned in not wanting the rate of interest to rise.”

After Williams’ comments, some of his Fed colleagues argued that it’s not clear there’s a need for yield curve control.

Still, the European Union is edging toward removing one of the obstacles for the ECB. Its 750 billion-euro recovery fund, which leaders hope to agree on this month, will be financed by jointly issued debt. If the economy deteriorates, the central bank will finally have a sizable amount of a single euro-zone asset to buy.

Read more...

|

The ECB has already embarked on yield curve control “in all but name” anyway, by scrapping limits for pandemic purchases that had constrained earlier programs, Citigroup Inc. strategists said in March, just after the program was announced. “Sellers have been warned; the ECB will buy.”

And it has. Since then, the central bank has bought far more Italian debt than its own guidelines would imply, again raising the prospect of accusations of monetary financing.

Policy makers say they’ll rebalance holdings at some point to stay within the law, though it’s unclear when that will be and how the ECB would react should such a move send spreads spiraling again.

”The yields on government debt differ among euro-area countries because economic fundamentals are different in each country; we don’t want to change that,” Isabel Schnabel, the ECB board member responsible for the bond-buying program, said last week. “But if suddenly, somewhere in the euro area, funding conditions worsen dramatically, then we have to counter this.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.