ECB’s Grasp on Inflation Is Weakening With the Pandemic Slump

The ECB feels it will be ‘well short’ of its inflation goal of just under 2% even three years from now.

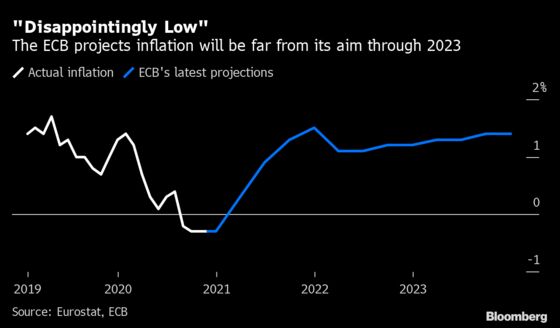

(Bloomberg) -- The European Central Bank made a stark admission last week as it announced a fresh round of policy measures -- even three years from now, it’ll still be well short of its inflation goal of just-under 2%.

President Christine Lagarde’s announcement of a 500 billion-euro ($606 billion), nine-month extension of the pandemic bond program, plus more long-term bank financing, left investors largely underwhelmed. Not only were those tweaks seen as relatively modest, they were presented alongside an inflation estimate for 2023 of just 1.4%, the lowest three-year forecast the ECB has ever made.

Such limited ambition is an acknowledgment that amid the historic growth slump because of Covid-19, one aim of central banks is to support the spending power of finance ministries by keeping their borrowing costs low. But unless further monetary action is signaled in the months ahead, Lagarde risks relying ever more on fiscal policy to attain her price-stability mandate.

“Any inflation-targeting central bank will need to be close to its target at the end of the forecast horizon or else it is doing something wrong,” said Anatoli Annenkov, senior economist at Societe Generale SA in London. “It is surprising to see such a low forecast.”

The ECB has long defined its mandate to achieve price stability in the currency bloc as annual inflation of “below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.” That goal was designed for an era when prices were more likely to gain too quickly than the opposite.

Since the global financial crisis more than a decade ago and amid the disinflationary effects of a period of hyper-globalization and technological advance, the region has been plagued with the stagnating effects of too-low inflation. The ECB has never sustainably met its target in the past decade.

In such a world, getting back to on-target inflation through monetary policy alone implies a massive expansion of stimulus. And given that policy makers and economists are already complaining that policies like quantitative easing are losing effectiveness, it’s hardly surprising that officials are not promising to bring out the big guns.

Thursday’s package was explicitly structured to preserve -- not ease -- financial conditions, and linked to the health crisis.

The pandemic stimulus programs are temporary, but the ECB’s original QE program that started in 2015 and traditional interest rates are permanently in the toolbox to be used to address the inflation shortfall. Still, by this time next year, the ECB will already own nearly half of Germany and Italy’s bonds, placing real limits on how much further they can go without crushing the market.

Likewise, further cuts to interest rates -- the benchmark deposit rate is -0.5% -- would exacerbate the already-weak profitability of Europe’s sclerotic banking system. When pressed on rates on Thursday, Lagarde responded with a marked lack of enthusiasm, saying merely that a rate cut remains “part of our toolbox.”

Losing Effectiveness

“Getting further easing of financial conditions from here is just very, very difficult,” said Nick Kounis, head of macro and financial markets research at ABN Amro Bank NV in Amsterdam. There’s a realization that “monetary policy is not really effective any more so what they’re trying to do is facilitate fiscal policy to do that job.”

The issue of whether and how the ECB can be more convincing about reaching its inflation goal is a key part of an indepth review of how the central bank operates. Some policy makers have called for so-called make-up strategies to be examined, which would allow inflation to rise above the goal after an extended period of missing it. The Fed unveiled a similar approach in July.

But without new tools or an unexpected acceleration in pent-up price gains, the ECB may be stuck waiting for fiscal policy to fill the gap by spending cash where the private sector can’t or won’t.

And while that front looks promising now -- European Union leaders finally agreed a 1.8 trillion euro multi-year spending package last week -- eventually European governments will have to rein in their ballooning debt somehow.

Japanification

That leaves the ECB in the subordinate position of trying to manage the cost of government borrowing, resembling the yield-curve control that the Bank of Japan openly engages in.

Euro-area monetary officials have vociferously denied they’re doing so. The distinction, according to Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel, is that the ECB is attempting to “preserve financial conditions” and not commit explicitly to keeping yields at a specified level, come what may.

It would be a messy business anyway, with the bloc comprising 19 different bond markets of varying importance. But investors are beginning to say the distinction doesn’t make much difference.

The ECB will “prioritize prices over quantities in the day-to-day implementation of its asset purchase programs,” said Konstantin Veit, senior portfolio manager for European rates at Pimco Europe GmbH in Munich. “Relying less on interest rates and more on asset purchases means that, like the BOJ, the ECB has de facto subordinated monetary policy to elected government officials in charge of fiscal policy.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.