ECB Rate-Cut Plan Puts Worried Banks on Lookout for Sweeteners

ECB Rate-Cut Plan Puts Worried Banks on Lookout for Sweeteners

(Bloomberg) -- Banks are waiting to hear how Mario Draghi plans to sweeten the bitter pill of more interest-rate cuts.

The European Central Bank president says if rates are reduced further below zero, as looks likely because of economic weakness, measures may be needed to prevent the policy from squeezing lenders’ profitability so much that they pull back on loans. Financial institutions have long complained that they can’t pass on the cost -- a charge on their overnight reserves -- to their depositors.

The latest evidence of that impact could come on Wednesday, when embattled German lender Deutsche Bank publishes its financial results. An ECB survey on Tuesday showed euro-area banks unexpectedly tightened credit standards for companies in the second quarter.

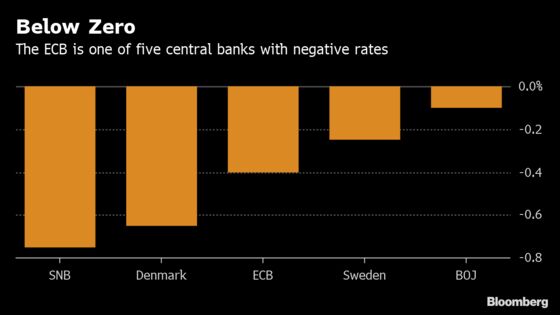

Of five central banks with negative rates, the ECB is the only one not to include offsetting measures. A fair system for the 19-nation euro zone is no simple matter though. Two-thirds of excess deposits are at German, French and Dutch banks, with only 10% at Italian and Spanish lenders. Here are some of the questions the Governing Council, which meets this week, must address:

How to do it?

The most common proposal is known as tiering, in which some overnight deposits are excluded or charged a different rate. The Swiss National Bank allows an exemption equal to 20 times the minimum reserve -- the cash that all banks are required to keep at the central bank. Anything above that is charged at 0.75%.

Denmark operates a two-tiered system in which some overnight money can be parked for free, but any excess is kept instead in one-week deposits penalized at 0.65%.

When the Bank of Japan went negative in 2016, it rolled out a three-tier system. Minimum reserves are exempt, as is liquidity acquired by banks that sold assets to the BOJ under its quantitative-easing program. Most funds beyond that are charged 0.1%.

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say

“The last decade has been rough for banks in the euro area and the ECB doesn’t want to make their return to health any more difficult. If the Governing Council lowers the deposit rate again and/or restarts its asset purchase program, as we forecast, the cost to lenders of the negative rate will increase. We therefore expect policy makers to introduce a tiering system in September that exempts a tranche of excess reserves from the charge.”

-- David Powell

How much should be exempted?

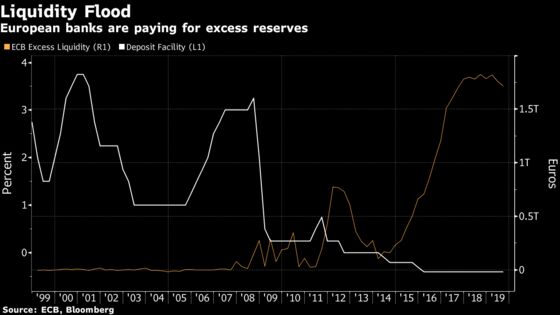

Euro-zone banks currently park more than 1.7 trillion euros ($1.9 trillion) in excess liquidity at the ECB each night. At a deposit rate of minus 0.4%, that costs them more than 7 billion euros a year. Executive Board member Benoit Coeure says that amount is “peanuts” and the real focus of attention should be dealing with technological competition and bad loans.

Analysts at Rabobank don’t think banks can bear much more though. They say the ECB is likely to cut its deposit rate as low as minus 0.8% over the coming year and, to fully offset that, about 800 billion euros of excess liquidity should be exempted.

Louis Harreau at Credit Agricole says the “hot potato” effect -- in which banks lend their cash to someone else to avoid the cost of holding it, so driving down interest rates for the whole economy -- stops working beyond a certain point. He says the ECB should first exempt 250 billion euros, and then increase the exceptions until a maximum of 1 trillion euros is subject to the negative rate.

Could it backfire?

Big exemptions mostly benefit banks with large deposits. In the euro area, those institutions are largely in the northern nations, inviting criticism that the stronger economies are being unfairly supported.

Banks with sizable exemptions might also feel less pressure to lend the cash out -- the ‘hot potato’ principle in reverse. That could hurt the market and push rates higher, especially in peripheral economies, according to economists at Barclays.

Moreover, the ECB’s TLTRO program of long-term loans to banks at cheap rates complicates things. Under certain circumstances that could throw up an arbitrage opportunity, according to Rabobank.

Barclays and Rabobank both say the ECB should subtract the TLTRO loans from each individual bank’s deposit-rate exemption. That would effectively create a group of net depositor banks -- mostly in northern Europe -- and net borrowers, mostly in the south.

Both groups would benefit. The net depositors would gain from exemptions under tiering, while net borrowers would be compensated by the generous terms on their TLTROs.

What else can the ECB do?

Draghi has always talked about “mitigation” of negative rates -- and that doesn’t have to mean tiering. One option might be for the ECB to start buying bank bonds, which would lower lenders’ funding costs as a way to offset the impact of another deposit-rate cut, according to Axa chief economist Gilles Moec, a former Bank of France official.

That would be controversial -- the ECB previously dismissed the idea of including bank debt in its QE program because its role as the euro area’s bank supervisor could create a conflict of interest. Still, Moec says all of the options on offer present a dilemma.

“We actually do not think that at this juncture it would rank very high in their preferences,” he said. “We simply consider that this approach would not be the most problematic on a menu which, unfortunately, is in any case quite unappealing.”

--With assistance from Nicholas Comfort.

To contact the reporter on this story: Piotr Skolimowski in Frankfurt at pskolimowski@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net, Jana Randow

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.