ECB Officials Talk About Flexibility. Here’s What They Mean: Q&A

ECB Officials Talk About Flexibility. Here’s What They Mean: Q&A

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

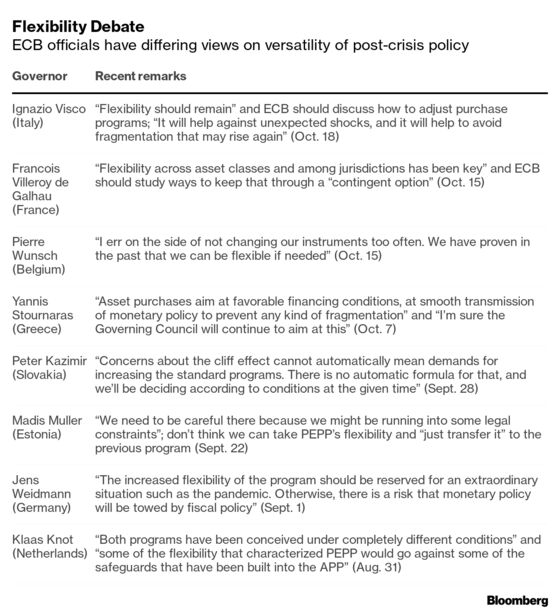

European Central Bank officials seeking “flexibility” for their future stimulus plans can’t quite agree on whether that means room for maneuver -- or room for potential expansion.

Beneath a veneer of consensus among some Governing Council members, around the need to preserve the versatility of their pandemic purchase program after it ends in March, lies a tension over how far they can bend pre-outbreak rules to pursue post-Covid monetary policy.

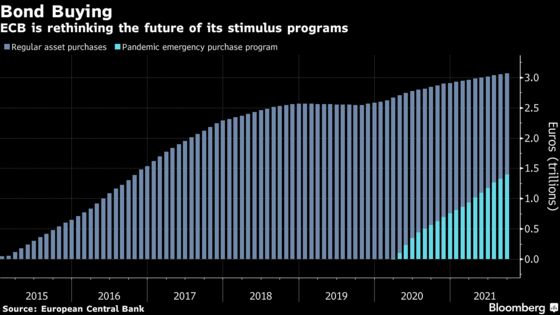

Officials are debating what should succeed the 1.85 trillion-euro ($2.1 trillion) bond-buying tool amid worries that its extraordinary design, intended to curb borrowing costs across the region during market stress, may still be needed as the recovery takes shape. They fear weaker economies such as Italy could face trouble if support is withdrawn too quickly.

“Once the pandemic period ends in their view, then their commitment to supporting financing conditions will also end in the way it is expressed today,” said Frederik Ducrozet, an economist at Banque Pictet & Cie in Geneva. “They’re going to want to signal in some way that the ECB will still backstop yields if everything goes wrong.”

Here’s a look at how the discussion is developing before a likely decision in December.

What was different during the pandemic?

When the ECB’s pandemic emergency purchase program -- known as PEPP -- was launched in March 2020, President Christine Lagarde proclaimed it to have “no limits,” allowing officials to direct aid where it was most needed.

That meant deviating from previous rules including so-called “issuer limits” which stop the Eurosystem holding more than 33% of a single government’s bonds. That still applies to the older Asset Purchase Program, known as APP, and is intended to prevent illegal monetary financing.

Officials also said PEPP would follow a “flexible” allocation of acquisitions across member states, rather than constantly adhering to the so-called “capital key” linking purchases to the relative size of each economy. In addition, the program included Greek government debt excluded from APP due to its junk ratings, and didn’t commit to an explicit monthly buying pace.

What elements of flexibility are likely to remain?

Including Greek bonds in that program is among the least controversial options, especially as the country may reach investment-grade status by 2022. Bank of Greece Governor Yannis Stournaras reckons the ECB will continue to buy the securities either way.

Applying some flexibility to the capital key could also outlive the crisis, especially since the ECB wasn’t too rigid about that rule in the past. But officials are unlikely to scrap it entirely. They could instead stipulate a point in the future by when holdings should meet the prescribed shares. PEPP buying has actually converged toward its allocated amounts in recent months, suggesting there hasn’t been much need for significant deviations.

Exempting future bond buying from issuer limits is likely to be more contentious, as it could raise legal issues. The problem is that, after more than six years of bond buying, the ECB is approaching those levels in some jurisdictions.

| What Bloomberg Economics Says... |

|---|

“The ECB has set a crucial precedent with PEPP -- no doubt the next crisis will also demand extraordinary flexibility too. If no contingent policy tool is formalized, policymakers can rely on their success in preserving loose conditions during the pandemic and enjoy the constructive ambiguity that affords -- they did what it took.” --Jamie Rush, Chief European Economist |

How will future bond buying work?

One workaround could include buying more European Union-issued debt, which has a higher issuer limit of 50%. That way public-sector purchases could run at higher amounts. Italian Governor Ignazio Visco says the ECB “may end up” doing just that.

Visco also favors a broad definition of “flexibility” for future programs -- saying that “it will help against unexpected shocks, and it will help to avoid fragmentation that may rise again.”

Others disagree. Belgian Governor Pierre Wunsch says the ECB has proved itself “flexible” in the past and can respond to shocks as they arise, rather than changing tools now. Estonia’s Madis Muller doesn’t think “we can take the flexibility that was there for PEPP and just transfer it.”

French Governor Francois Villeroy de Galhau last week suggested something of a middle way, proposing a “contingent option” that needn’t be part of the pre-existing bond-purchase tool. It would be available to activate if needed and grant more freedom than before to buy debt securities of different countries at times of stress.

When will this be decided?

Officials will participate in a number of seminars to discuss the options before December, when they are widely expected to announce their decision on the next steps. Most economists expect the ECB will step up the 20-billion-euro purchase pace of its APP program to 40 billion euros per month after PEPP expires in March.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.