ECB Finally Hears EU Cavalry Coming to Help Its Crisis Fight

ECB Finally Hears EU’s Cavalry Coming to Its Aid in Crisis Fight

(Bloomberg) -- The European Central Bank is on the verge of finally getting proper help from politicians to fight the region’s economic battles, even if it stays alone on the front line for now.

The proposal by German and French leaders for a 500 billion-euro ($546 billion) aid package to help the European Union shake off the coronavirus pandemic is seen by analysts as a significant step toward a stronger common fiscal policy, complementing the euro’s monetary foundations.

That’s something ECB President Christine Lagarde and her predecessors have long craved. For starters, the central bank should have to step in less often to prevent debt crises. It should also be less exposed to legal battles that have cast a shadow over its bond-buying programs, and it could even get help hitting its inflation goal.

“The ECB has been doing the heavy lifting of supporting the entire euro-zone economy,” said Andrew Bosomworth, managing director and head of portfolio management in Germany at Pacific Investment Management Co. “Now for the first time we would have the equivalent of a fiscal counterpart.”

Lagarde won’t get backup right away. The Franco-German plan must be supported by all 27 EU members, and disputes over whether aid should be grants or loans are already simmering. Even if agreed, money would only arrive next year.

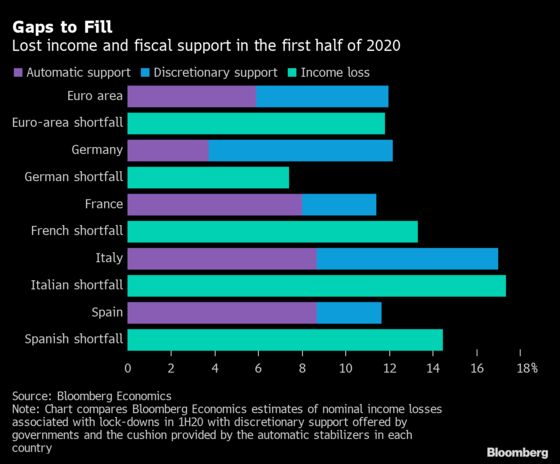

It’s also well short of the full fiscal cost of the pandemic, which the ECB puts at between 1 trillion and 1.5 trillion euros, and Bloomberg Economics says could be 2.5 trillion euros in a worst-case scenario.

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say

“There is at least some willingness to meaningfully share the costs of the crisis with those countries most badly-affected. What we do not yet know is how broad that support is or how deep it would run if the crisis escalated. Even so, it’s a step in the right direction and should be a source of comfort for the ECB.”

-Jamie Rush, Maeva Cousin and David Powell. Read their EURO-AREA INSIGHT

Before the proposal, most economists expected the ECB to bolster its 750 billion-euro pandemic bond-buying program to soak up debt issuance, perhaps as soon as the June 4 meeting, and there’s little sign those predictions are changing.

“The Franco-German deal is very encouraging, but even if it is agreed without dilution, the ECB is likely to remain in ‘preventive easing’ mode,” said Banque Pictet & Cie’s Frederik Ducrozet. “This is no time to claim victory.”

Yet Italian bond yields did sink on the news, and Lagarde -- who praised the deal as a “testament to the spirit of solidarity and responsibility” -- has reason to be optimistic. Her institution is embroiled in financial, legal and economic battles, and the plan can help with all three.

Financial Frailty

While the ECB’s job is to ensure price stability, its pandemic emergency program also addresses a more urgent need -- stabilizing markets. That means buying vast quantities of Italian government bonds, whose yields were surging because investors fear the indebted country, one of the worst-hit by the virus, would struggle to pay for its fiscal response.

The recovery plan “might make the ECB’s job easier because it helps to improve market sentiment toward countries like Italy,” said Nick Kounis, an economist at ABN Amro. “If it’s successful, the ECB will have to worry less about dealing with fragmentation across the euro area and focus more on conventional tasks of monetary policy like inflation.”

The EU fund would be backed by countries based on economic size, and issue aid according to need. In effect, heavyweights like Germany would support struggling neighbors such as Italy, though conditions are still to be negotiated.

In an interview published after the proposal, the ECB chief encouraged politicians to combine grants with very long-term loans -- at least 10 years and perhaps 30 years -- at low interest rates.

Legal Aid

Lagarde, a lawyer, is also likely to be alert to a potential legal advantage for the ECB. The mechanism for financing the fund would be bonds issued by the European Commission, and while national politicians in Germany and the Netherlands will likely argue that’s not the same as mutual debt -- which they oppose -- it’s close.

The central bank currently aims to spread bond purchases across the region according to each national economy’s size as part of measures to avoid breaching EU law on monetary financing.

Debt issued by the commission, so not directly tied to any single country, would give some additional leeway. That’s a plus for the ECB, which has faced persistent challenges over its bond-buying programs -- including an unexpectedly negative ruling in Germany’s top court this month.

“The ECB would presumably buy the bonds issued to finance the fund,” said Rishi Mishra, an analyst at Futures First. “ They could buy that debt on to their balance sheet without too much trouble.”

Price Push

Longer term, the recovery fund provides spending power that the ECB has long urged governments to use to lift the euro-zone economy.

The central bank has been pumping monetary stimulus into the financial system almost continuously since the sovereign debt crisis, yet consumer-price growth has remained stubbornly short of its goal of just-under 2%.

With borrowing costs below zero and the deepest peacetime recession in almost a century, there’s little excuse now for governments not to splurge.

“This is important,” said ABN Amro’s Kounis. “Because over the coming months and years they are going to have a hell of a job trying to boost inflation after the crisis is finally over.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.