ECB Faces Ghost of Rate Hikes Past a Decade After 2008 Misstep

The ECB raised interest rates in 2008 global recession, it now risks waiting too long to tighten monetary policy.

(Bloomberg) -- A decade to the day since the European Central Bank raised interest rates on the cusp of the global financial crisis, some believe it now risks waiting too long to tighten monetary policy.

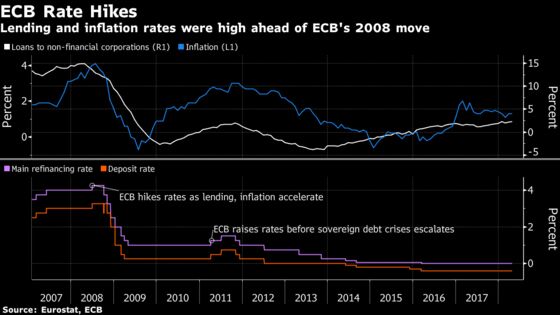

On July 3, 2008, the ECB hiked borrowing costs to combat inflation that was running more than twice as high as its target. By October, it was hitting reverse as prices slumped and economic growth evaporated amid the worst economic emergency since the Great Depression.

President Mario Draghi was on the ECB’s decision-making Governing Council as Bank of Italy chief at the time, and in 2011 when borrowing costs were hiked just before Europe’s debt crisis. Perhaps informed by those experiences, he’s now ruling out raising rates until after the summer of 2019.

Draghi’s guidance was cheered by markets as prudent when it was unveiled last month. Economists and investors who had expected a rate hike in the middle of 2019 pushed out their forecasts to late in the year. But a few see a bigger threat -- that the ECB becomes trapped in a zero-interest-rate world as the economic cycle turns down.

“There is a real risk the ECB never starts hiking,” said Patrick Artus, chief economist at Natixis in Paris. “The consensus is that the ECB is right, but it could be behind the curve and you end up with zero rates for a long time.”

Changed Times

The argument for staying on hold for a while rests on the fact that the inflation outlook today is very different. In 2008, price growth was 4 percent. The rate is now 2 percent, but that’s largely driven by oil costs -- underlying inflation, excluding energy and food, is half as fast. Wage growth is only just starting to pick up and the economy is threatened by mounting trade tensions and populism.

“They are being extremely cautious exactly because they’ve been burnt before,” said Marco Valli, an economist at UniCredit in Milan. “In the current environment, visibility for policy makers is very low.”

The flipside is that the euro area is more robust than 10 years ago, and so more capable of withstanding higher rates. New crisis-busting tools are in place, the ECB has a wider range of instruments to hand, and euro-area banks are under closer scrutiny.

There’s no firm agreement even among experts on the right timing. Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers said at an ECB conference last month that central banks should wait until they see “the whites of their eyes” of inflation, arguing that the damage from another recession would “massively exceed” the cost of prices running slightly hot.

Be Prepared

The Bank for International Settlements, which coordinates central-bank discussions and research into monetary and financial stability, has repeatedly warned against delaying the end of crisis-era stimulus, saying policy makers shouldn’t be put off by market volatility. Acting sooner would also create more space to loosen policy when the next downturn hits.

“What’s important for a central bank is that when growth is solid and inflation rates are close to the level one would like to have, that one tries to raise interest rates,” said Gertrude Tumpel-Gugerell, who was on the ECB’s Executive Board for the 2008 rate hike. “You always need an instrument in case of a negative shock."

The U.S. economy, now in its ninth year of expansion, could be one drag. Capital Economics expects growth to slow enough that the Federal Reserve will start cutting rates early in 2020, and notes that 2008 was the only time the ECB has tightened policy while the Fed was easing.

Draghi has vowed to be “patient” in timing the first rate hike, but his term expires in October next year. One of the favorites to succeed him, Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann, has typically taken a far more critical view of loose policy, including opposing the introduction of quantitative easing.

What Our Economists Say“If growth keeps chugging along and inflation accelerates faster than forecast, the ECB may find itself playing catch up. Rates could go up at a quicker pace, especially if the hawkish Jens Weidman takes the helm when President Mario Draghi’s term end.”-- David Powell and Jamie Murray, Bloomberg Economics. Read their EURO-AREA INSIGHT |

Economists at JPMorgan Chase said in a note last week that they also see the ECB’s stance as too loose, but that they expect a “hawkish tilt in guidance” to avoid overshooting only when officials are certain consumer-price growth is solidly on an upward path.

“The ECB will continue its very cautious exit path,” said Oliver Rakau, an economist with Berenberg in Frankfurt. “It has gained the credibility to not need to over-react to short-term inflation developments in one direction or the other.”

--With assistance from Carolynn Look.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alessandro Speciale in Frankfurt at aspeciale@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net, Fergal O'Brien

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.