Down $290 Billion, China Tech Investors Wargame Worst-Case Scenarios

With 22 pages of vaguely worded edicts, China has cast doubt on the future of its biggest internet companies and ignited selloff.

(Bloomberg) -- With 22 pages of vaguely worded edicts, China has cast doubt on the future of its biggest internet companies and ignited a $290 billion equity selloff.

Investors are now gaming out how bad it might get for Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., Tencent Holdings Ltd. and other Chinese internet giants as Xi Jinping’s government prepares to roll out a raft of new anti-monopoly regulations.

As is almost always the case, the country’s leaders have said little about how harshly they plan to clamp down or why they decided to act now. But the draft rules released Tuesday give the government wide latitude to rein in tech entrepreneurs like Jack Ma who until recently enjoyed an unusual amount of freedom to expand their empires across nearly every aspect of Chinese life.

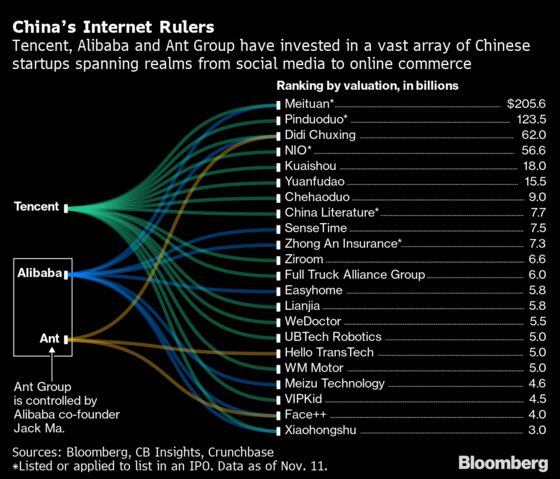

The country’s internet ecosystem -- which has long been protected from competition by the likes of Google and Facebook -- is dominated by two companies, Alibaba and Tencent, through a labyrinthine network of investment that encompasses the vast majority of the country’s startups in arenas from AI (SenseTime, Megvii) to fresh veggies (Meicai) and digital finance (Ant Group). Their patronage has also groomed a new generation of titans including food and travel giant Meituan and Didi Chuxing -- China’s Uber. Those that prosper outside their aura, the largest being TikTok-owner ByteDance Ltd., are rare.

The anti-monopoly rules now threaten to upset that status quo with a range of potential outcomes, from a benign scenario of fines to a break-up of industry leaders. While few China watchers claim to know where in that spectrum authorities will land, most view this week as a turning point.

“The Wild West era of policy arbitrage -- taking advantage of weak regulations over the sector -- has come to an end,” said John Dong, a securities attorney at Joint-Win Partners in Shanghai.

Here are some of the scenarios analysts and investors are considering:

Mild

Optimists say regulators are merely re-asserting their right to oversee internet companies, without trying to initiate drastic change.

Even if authorities do take action, China has a tradition of cracking down in fits and starts, or making examples out of high-profile companies. Tencent, for instance, became a prominent target of a campaign to combat gaming addiction among children in 2018. While its shares took a hit, they eventually recovered to all-time highs. Alibaba has done the same after running afoul of authorities on everything from unfairly squeezing merchants to turning a blind eye to fakes. Both companies were worth around $800 billion before shares began tanking this month.

“Each internet leader may face some impact and have to adjust their practices, but the regulations will unlikely affect their leadership,” said Elinor Leung, an analyst at CLSA Ltd. in Hong Kong. “Internet platforms, by nature, are scale businesses.”

Liu Bo, Alibaba’s general manager of Tmall marketing and operations, said on the sidelines of the company’s Singles’ Day celebration on Wednesday that he wasn’t surprised by the new rules and that the government was “improving” oversight across various industries.

Chinese internet stocks led by Meituan and Tencent gained at least 3% Thursday, recouping some of their two-day loss.

Bad

Some analysts predict there’s a crackdown coming, but a targeted one. They point to language in the regulations that suggests a heavy focus on online commerce, from forced exclusive arrangements with merchants known as “Pick One of Two” to algorithm-based prices favoring new users. The regulations specifically warn against selling at below-cost to weed out rivals.

Those kinds of strategies helped drive eBay Inc. and Amazon.com Inc. out of China and have led companies including Alibaba, JD.com Inc., and upstart Pinduoduo Inc. to accuse each other of using underhanded tactics.

Also embedded within the rules is a reference to the need for official approval on all mergers and acquisitions involving Variable Interest Entities. The VIE model has never been formally endorsed by Beijing but has been used by tech titans such as Alibaba to list shares overseas. Under the structure, Chinese corporations transfer profits to an offshore entity with shares that foreign investors can then own. Pioneered by Sina Corp. and its investment bankers during a 2000 initial public offering, the VIE framework rests on shaky legal ground and foreign investors have been perennially nervous about their bets unwinding overnight.

“The VIE structure has been operating in a gray area in China, and till this date, there’s no law saying if it’s illegal or not,” said Zhan Hao, managing partner of Beijing-based Anjie Law Firm, who specializes in antitrust.

One worry is that uncertainty surrounding the new rules will chill investment, acquisitions and venture capital funding until officials shed more light on what they’re prepared to do.

Nightmare

Most worst-case scenarios revolve around the idea that China’s leaders have grown frustrated with the swagger of tech billionaires and want to teach them a lesson by breaking up their companies -- even if it means short-term pain for the economy and markets.

China’s private sector has maintained a delicate relationship with the Communist Party for decades, and has only recently been recognized as central to the nation’s future. Many commentators have attributed the recent crackdown on fintech companies to remarks Jack Ma made at a conference in October, when he decried attempts to rein in the burgeoning field as short-sighted and outmoded.

Buried within the anti-monopoly rules is a paragraph brandishing vague but seemingly dire threats: Companies that violate anti-monopoly regulations may be barred from acquisitions. And if they’re to be allowed to proceed, they may be forced to divest assets, share intellectual property or technologies, or open up infrastructure to competitors and adjust their algorithms.

“It’s highly likely that the guidelines will bring about the eventual splitting off of subsidiaries, and could result in the elimination of a lot of non-compliant smaller firms,” said Dong at Joint-Win Partners. “No country in the world would allow all these to exist in one huge entity.”

Alibaba, Ant and Tencent alone commanded a combined market capitalization of nearly $2 trillion before last week, easily surpassing state-owned behemoths like Bank of China Ltd. as the country’s most valuable companies.

Alibaba and Tencent are also key backers of leaders in adjacent industries, such as Wang Xing’s food delivery giant Meituan and car-hailing leader Didi. They’ve invested billions of dollars in hundreds of up-and-coming mobile and internet companies, gaining kingmaker status in the world’s largest smartphone and internet market by users.

“There shouldn’t be a shred of a doubt by now for internet companies -- never question the drive or the determination of the regulators,” Dong said. “There’s no such thing as too big to fail, not in China.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg