Don’t Give Up on Bringing Manufacturing Back to the U.S.

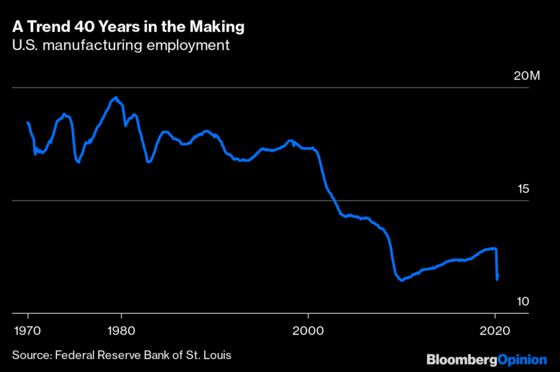

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- More than three years ago, Donald Trump was elected president on a promise to bring U.S. manufacturing back from China. Even before the coronavirus pandemic hit, Trump’s economic expansion -- which became the longest on record -- didn’t even manage to restore all the manufacturing jobs lost in the Great Recession, much less reverse the declines of the previous decade:

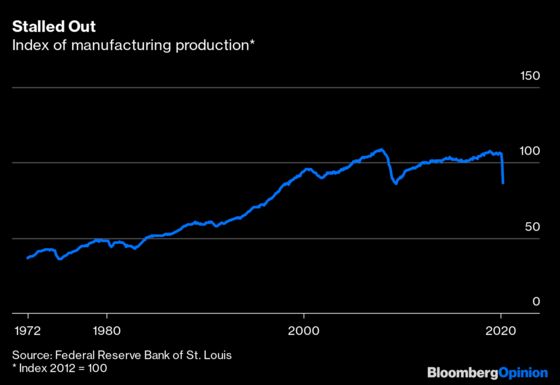

Nor was it simply a case of automation taking over from human laborers. Manufacturing production fell in 2019, and never reached its pre-2008 peak:

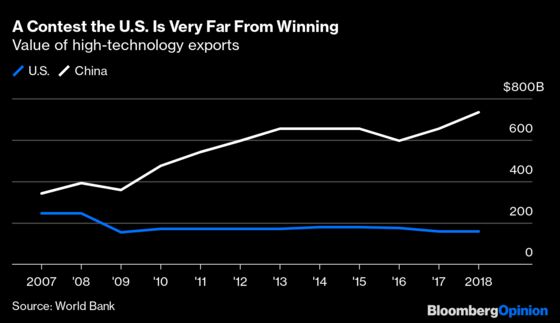

Trump’s trade war not only didn't resuscitate U.S. manufacturing, it also did nothing to move global supply chains out of East Asia. U.S. high-technology exports languished under Trump, while China’s soared:

Trump’s ineffective efforts make one thing abundantly clear: If high-value manufacturing industries and factory jobs are ever going to return to the U.S., it’s going to take a lot more than tariffs and bellicose rhetoric.

But some thinkers on the political right are ready to take a more serious stab at the idea. The Reshoring Initiative, a policy plan released by the new think tank American Compass, has collected a number of big ideas aimed at making the U.S. a manufacturing powerhouse once again.

Abandoning the gospel of free trade and embracing industrial policy is a huge leap for the political right; it’s a stance more typical of left-leaning thinkers aligned with organized labor. The Reshoring Initiative’s authors give a number of justifications for this tectonic shift. First, they cite the traditional concerns of U.S. national security and soft power. They also mention resilience to global supply-chain shocks -- a weakness of the traditional free-trade system that was glaringly exposed by the coronavirus shutdowns. Finally, they assert that bringing supply chains back within the U.S. is useful for productivity and innovation.

These last two assertions are the most contentious. The traditional case for free trade is based on the notion that when countries divide up production according to what each one specializes in, productivity improves. For example, economists typically believe that combining cheap labor in developing countries with the capital and know-how of developed nations bears dividends for both. But some dissent, arguing that countries that perform a greater variety of economic activities grow faster, possibly because knowledge and talent flows between upstream and downstream companies in a supply chain.

Proponents of free trade also claim that international supply chains increase innovation, arguing that companies exposed to global competition are forced to innovate more in order to keep up. The evidence on this proposition is mixed; some papers claim that import competition from China makes companies in developed countries more innovative, while others claim the exact opposite.

Given the difficulty of untangling the webs of cause and effect in world-trade patterns, neither dispute is likely to be resolved any time soon. Thus, the Reshoring Initiative represents a large gamble -- a wholesale reordering of the relationship between government and industry in the U.S. that goes against decades of orthodoxy.

And it would be a substantial reordering. The Reshoring Initiative recommends not just traditional policies such as workforce training and tax incentives, but bold and novel steps like domestic-content requirements for manufacturers, major alterations to the World Trade Organization and government-sponsored corporate research consortiums. Rather than merely providing the inputs to make U.S. industry more competitive, these are policies that would heavily involve the government in telling private business what to produce and where to produce it. The last time such a reorientation occurred was during World War II.

Furthermore, there’s a substantial chance that even these efforts, like Trump’s trade war, will come to naught. The forces of economic clustering are extremely hard to overcome; East Asia is home not just to the deep capital resources of China and the cheap workforces of Southeast Asia, but to the high-tech companies of Japan, Taiwan and South Korea. Besides being a deep repository of know-how, capital and labor, the region also boasts an enormous consumer base that already eclipses that of the U.S. That titanic economic agglomeration creates its own force of gravity that the sparsely populated continent of North America will struggle to supplant. Faced with those enormous fundamental forces, it’s small wonder that most analysts are highly skeptical of the idea of reshoring.

But nevertheless, it’s good that ideas like the Reshoring Initiative are being thrown around, because sticking with the current system should also be regarded as a gamble. With median incomes largely stagnant, inequality rising, productivity growth slowing and high-technology industries shifting away from the U.S., not doing anything should also be regarded as risky. Industrial policy also probably makes for good politics -- by offering Americans a concrete vision of what their economy could look like, instead of leaving it up to the vagaries of the market, the authors of the Reshoring Initiative may be able to gather broad support for a cohesive growth strategy, even if it isn’t a perfect one. The U.S. economic strategy of leaving industrial policy to the whims of the market has hit the point of severely diminishing returns, so it’s time to brainstorm new approaches.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.