Dirty Indian Politics Has No Answer for the World’s Most Toxic Air

The politics of pollution in India’s capital New Delhi are as noxious as city’s air.

(Bloomberg) -- The politics of pollution in India’s capital New Delhi are as noxious as city’s air.

While Delhi chokes, politicians squabble in an annual phenomenon that lasts for an intense few weeks at the start of winter, then dies down as pollution levels fall. What they haven’t done is come together to find sustainable solutions to one of the world’s worst air pollution problems that by the World Bank’s calculations costs the country as much as 8.5% of its GDP, or around $221 billion each year.

Home to seven of the 10 most polluted cities in the world, India’s deadly haze was responsible for one of every eight deaths in 2017, while the life of a child born today is likely to be 2.5 years shorter because of air pollution. Delhi, with its unlikely combination of sweeping green boulevards and sprawling, unchecked urban growth, has become the symbol of the country’s struggle to contain this toxic cloud.

Describing the city as “gas chamber,” Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal said crop burning in the states of Punjab and Haryana was a key source of pollution, and called on Prime Minister Narendra Modi to intervene. The federal environment minister Prakash Javadekar blamed Kejriwal’s administration for not taking serious measures, while his colleague, Health Minister Harsh Vardhan, suggested in a tweet eating carrots could help beat pollution-related harm.

So far Modi has not issued a statement on the crisis, which prompted the declaration of a public health emergency and the closure of schools for several days. Calls to the prime minister’s office went unanswered.

“One key reason for the air pollution governance falling short is the absence of commitment and initiative by the political executive,” said Santosh Harish, environment researcher at the New Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research, adding most policy measures had been taken at the behest of judiciary. “They are negligent in taking on issues of air pollution as a sense of urgency.”

The country’s politicians should be on a war footing, Harish said, and address the lack of staff, equipment and enforcement power in pollution control boards, inefficiency in public transport systems and insufficient clean power generation.

Global Concerns

China -- which is also battling deadly air pollution -- reduced the annual average concentration of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) by a third between 2013 and 2017 in 74 cities, according to the State of Global Air 2019 study. India has long struggled to pull together a similarly coordinated national approach.

”China’s society had strongly expressed their needs for clean air and health when facing air pollution, thus the government took more emphasis on the issue,” said Ma Jun, founder and director of the Beijing-based Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs. There had not been a similar, significant public outcry in India, Ma said. “If there’s not enough consensus from the public, it’s hard for policy makers to be determined to tackle the issue.”

Air pollution drives up costs for companies, affecting both the bottom line and productivity, particularly when staff suffer respiratory diseases, said Hemant Shivakumar, a senior consultant at Control Risks. “In the absence of action by the government, this can become a long term risk and companies would want some kind of initiative to be taken.”

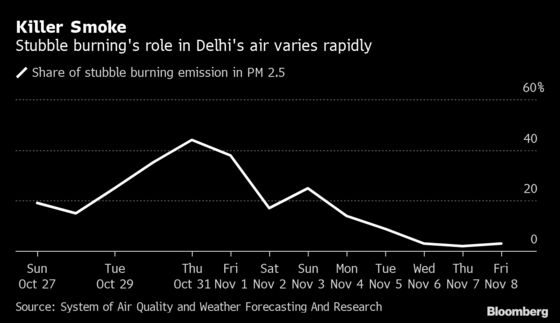

The South Asian nation’s toxic air is driven by a combination of factors, including vehicular emissions, factory emissions, road dust and construction activities. Crop burning contributed 44% to Delhi’s soaring PM 2.5 levels on Oct. 31, dropping to 2% by Nov. 7, according to System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting.

Small scale farmers have been burning to prepare their land for planting for hundreds of years, said Helena Varkkey, an expert on air pollution and lecturer at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur, noting baseline pollution in many Asian cities was also high, due to domestic, vehicular and industrial emissions. “If governments focus on these constant issues outside the major haze seasons, there could be a significant improvement on air quality as a whole,” Varkkey said.

‘Out of Hand’

India’s farmers, already struggling with depressed crop prices, are tired of shouldering responsibility for the crisis.

“They blame farmers because farmers are the easiest people to beat,” said V.M. Singh, convener of the All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee, a group representing around 250 farmer’s organizations. He urged governments to focus on programs to generate income from crop stubble, rather than expecting farmers to shoulder costs themselves.

“Either you take stubble away from farmers or you provide a cheap affordable technological solution to them,” said Sagnik Dey, associate professor of atmospheric sciences at Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi. “You can’t expect farmers to bear those high costs.”

Modi’s government has promoted solar power, improved emission standards and handed out millions of gas canisters to households to reduce cooking over open fires. In January it launched the National Clean Air Program. But the measures have yet to alleviate the impact of India’s rampant growth, from the dust left by thousands of new construction sites to exhaust from millions of cars.

“The situation is getting out of hand,” said Dey. “The real frustration is that we know what to do but we are not able to implement it because of lack of coordination and limited resources.”

--With assistance from Manish Modi, Adrian Leung and Feifei Shen.

To contact the reporters on this story: Bibhudatta Pradhan in New Delhi at bpradhan@bloomberg.net;Ragini Saxena in Mumbai at rsaxena30@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Ruth Pollard at rpollard2@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.