Deflation Alarm in Spain Tests Lagarde’s Optimism on Prices

Deflation Alarm in Spain Tests Lagarde’s Optimism on Prices

(Bloomberg) -- When the coronavirus hit Europe this year, Manuel Vegas asked his Spanish association of hotel directors to avoid cutting room costs by more than 25%. Instead, they plunged as much as 60%, and he reckons “we won’t get back to 2019 prices until at least 2023.”

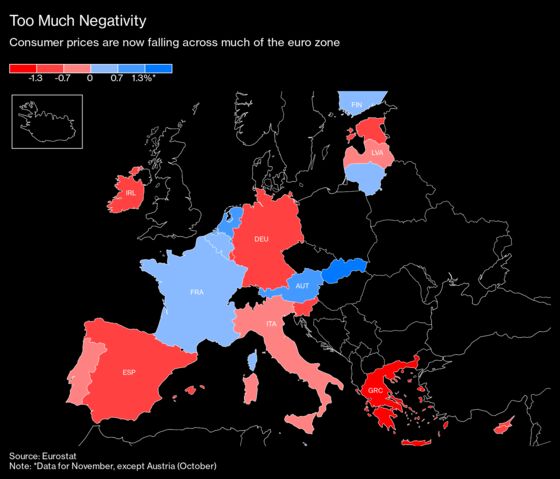

Falling prices can be found across the continent as economic restrictions and job insecurity deter spending. But in some quarters it’s the fear of steep and entrenched declines -- a deflationary trap that drags wages and ultimately brings the whole economy down -- that has people like Vegas worried most.

Weaker economies, and those more reliant on services such as tourism, are at the greatest risk, putting much of southern Europe once again in danger. Of the seven euro-area nations on the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas, only France and Malta have positive rates of inflation. Spain’s is -0.9%, Greece’s is -2%.

BE Primer: Italy Faces Grave Deflation Threat From Virus Damage

Policy makers in Madrid are also making the case that the rest of the bloc isn’t immune though. Subzero inflation in places such as Germany may be largely explained by tax cuts and lower energy bills, but the perception of falling prices can take hold if it persuades consumers to put off spending now in the hope of a better deal later.

“We are seeing an increase in the portion of goods whose prices are increasing very little or falling, which is a sign of the risk” in the euro zone, Oscar Arce, the Bank of Spain’s chief economist, said in an interview last month.

So far, the European Central Bank isn’t too worried. While it will almost certainly boost monetary stimulus next week, that’s to counter the shock of the second wave of the pandemic. It projects inflation -- currently the weakest since 2016 at -0.3% -- will turn positive next year.

President Christine Lagarde declared on Oct. 29 that she didn’t foresee deflationary threats “at all.” Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel said this week the aim of stimulus should be to maintain current financial conditions, not make them even looser.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“A period of stubbornly weak inflation is a dangerous starting point for an economy once again subject to lockdowns and the ECB has expressed increasing concern about the persistence of ultra-low inflation. We expect more stimulus at the December meeting.”

-Jamie Rush

To read the full report, click here.

That’s a view shared by some economists, who say a swift growth rebound after the crisis subsides will kill any deflationary pressures.

“When the economy is back in shape, we’ll see prices increase again,” said Jesus Fernandez-Villaverde, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. “People will realize there is a lot of accumulated demand.”

Even Bank of Greece Governor Yannis Stournaras is banking on such a bounceback. While acknowledging that his nation’s price declines have postponed spending and deepened the recession, he said in an interview that “with the recovery of the economy next year, the inflation rate will become positive again.”

One factor that could help southern Europe in particular is the European Union’s 1.8 trillion-euro ($2.2 trillion) enhanced budget and recovery fund, which will disburse grants and cheap loans to countries to aid the recovery from the pandemic.

That spending, though temporary, counters an underlying weakness in the euro zone. While the ECB strives to stabilize inflation at just under 2%, that’s an average for the bloc as a whole, risking some countries being left behind. Fiscal support can help plug that gap -- one reason why the ECB has long argued for a permanent such facility.

Japan Worry

Still, Jordi Gali, an economist at Spain’s Research Center for International Economy, wonders if the pandemic might have had a deeper impact by permanently instilling caution in consumers, with consequences for prices.

“We may be in a situation -- and this is extremely uncertain because we don’t have a precedent in recent times -- in which savings remain abnormally high,” Gali said. “The concern is that we may get trapped in this very low level of inflation that could be negative or slightly negative like in Japan over much of the past three decades.”

Such a risk is what officials such as Arce, and his boss, Bank of Spain Governor Pablo Hernandez de Cos, warn the euro region is facing if the ECB doesn’t act decisively enough.

Even if their colleagues in Frankfurt don’t buy into that argument next week, it could factor into future decisions both on easing and on the redesign of its monetary policy framework.

The central bank is already discussing shifting the definition of its price-stability goal in a way that could allow for overshooting on inflation after long periods of weakness. It is mulling a new target of 2%, rather than “close to but below 2%.”

For Athanasios Orphanides, a former ECB Governing Council member, that last change is a no-brainer -- and should be enacted immediately rather than when the strategic review ends around the second half of next year.

“If the average is too low, as the ECB has been maintaining after the euro crisis, then more states actually enter into deflation territory,” he said. “That’s one reason it’s bad policy for the ECB to be maintaining this ‘lowflation’ regime.”

It’s a view Spain’s hotel managers would recognize, even if they don’t follow the details of the ECB’s policy debates.

“We will be living with the scars from this crisis for some time,” Vegas said. “Not just in Spain, but across Europe.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.