Coronavirus Wreaks Havoc on the Future of U.S. Immigrant Labor

Coronavirus Wreaks Havoc on the Future of U.S. Immigrant Labor

(Bloomberg) --

Rosibel Alvarenga’s job as a cook at a restaurant in downtown Washington provided steady income and job security for 15 years.

When the American bistro closed temporarily in the coronavirus shutdown, she continued receiving a paycheck. Once operations resume, her pre-virus earning potential may not.

“We’ve been told that each of us may only be needed one or two days a week,” says Alvarenga, who typically worked five. “We’re worried, because we simply don’t know what the future holds.”

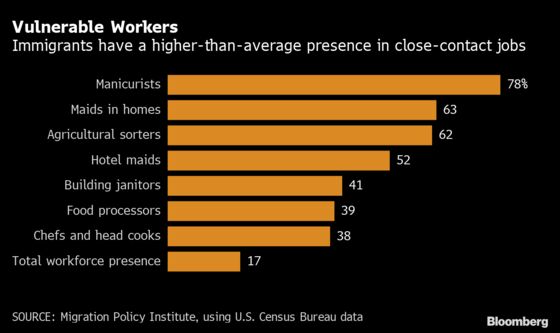

The pandemic is reshaping the job market for millions of immigrants in the U.S. Consumers may be slow to return to the hotels, office buildings and manicure parlors where many are employed.

Over time, the very nature of the work some immigrants do is likely to change as businesses enforce new social-distancing and related requirements. Meat workers, the backbone of the food-supply chain, toil in close quarters and at least 30 have died of coronavirus, with more than 10,000 infected or exposed.

The reduced job opportunities, combined with President Donald Trump’s hard-line policies, mean the number of undocumented immigrants is likely to tumble, said Andrew Selee, president of the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington think tank.

5% of Employment

They contribute about 3% to U.S. gross domestic product annually and account for 5% of employment, according to a 2016 paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Removing all of them would cost the economy as much as $5 trillion over 10 years, the report found.

“We’re probably going to have low immigration, particularly low illegal immigration, for a while,” Selee said. “There just isn’t the jobs magnet that was present for so long.”

Undocumented immigrants face the double hit of unemployment and a lack of access to social safety-net programs, including the stimulus checks the U.S. government sent out, said Juan Navarrete, director of programming for Casa, an immigrant-aid organization in the Washington area.

| Read more: |

|

“A lot of these people are out of work -- they can’t pay for rent, they can’t pay the utilities,” Navarrete said. “Many of them don’t have health insurance, and they can’t get the government checks.”

The U.S. labor market is in the throes of the harshest downturn in history. Employers cut an unprecedented 20.5 million jobs in April and the unemployment rate more than tripled to 14.7%, the highest since the Great Depression era of the 1930s. The initial losses were concentrated in lower-wage labor, from hospitality to retail and restaurants, and surveys show that many small businesses may never reopen.

Trump last month suspended most immigrant visas for 60 days in what he described as a bid to limit competition for jobs. Separately, lengthy detentions of undocumented migrants crossing the Mexico border fell by half in April to fewer than 17,000. That’s because U.S. Customs and Border Protection used its emergency public-health authority to expel migrants within hours of their arrival, rather than housing them in American border stations as before.

Leaving for Home

There are signs that some immigrants already are deciding to leave. Those from Mexico sent family and friends a record $4.02 billion in remittances in March. But that partly reflects repatriation of savings by people who’ve lost hope for their job prospects in the U.S. and plan to go home, said Michael Clemens, director of migration, displacement and humanitarian policy at the Center for Global Development.

“It could be a sign that more and more people are at least temporarily giving up on their future here,” he said.

In the longer term, remittances are expected to drop as immigrants who remain in the U.S. deal with the virus’s impact on the job market. The World Bank forecasts a record 20% decline globally in transfers to low- and middle-income countries.

Alvarenga, 53 years old and a legal permanent resident, says she’s reduced by one third the money she usually sends her mother and sister in El Salvador because she’s uncertain about her job.

Amid the earnings uncertainty, Alvarenga has started cooking food on her back porch -- including pupusas, a Salvadorean flatbread stuffed with cheese and pork -- on weekends to sell to friends and neighbors.

Struggling With Bills

David Perez, 43, has struggled to pay the bills since the Elkridge, Maryland, flea market where he sells leather goods from his native Mexico shut down in March. He already lost his car because he couldn’t make the payments. The single father hasn’t paid this month’s $1,095 rent for his apartment outside Baltimore and doesn’t know how he’s going to afford it.

Perez’s 14-year-old daughter, Maria, has had trouble keeping up with her school work because her father can’t afford internet at home. Given the challenges, Perez has completely halted the cash transfers that help put food on the table of his mother back home in the state of Puebla.

“I’ve thought about leaving,” he said. “If the situation remains as complicated as it is, I’m going to need to return.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.