Coronavirus Shows Scale of Task to Fix China’s Flawed Healthcare

Coronavirus Shows Scale of Task to Fix China’s Flawed Healthcare

(Bloomberg) -- Even before the deadly coronavirus epidemic struck, China faced a monumental task to bring its healthcare system up to scratch.

Now, the scale of that challenge has been highlighted after the virus exposed an over-reliance on big hospitals in major cities and shortcomings in how the state responds to emergencies, even with a mechanism built after the SARS outbreak in 2003 in place.

The extensive economic fallout from Covid-19 is set to trigger a renewed focus on fixing the healthcare system, just as SARS did 17 years ago. China already has an ambitious goal of building a world-class system this decade.

There would be broader economic dividends from doing so. The average Chinese household currently saves about 45% of its income, in part to cover costs like medical bills. A better social safety net with higher-quality healthcare would help unleash more consumption as families reduce their precautionary savings.

China envisions a 16 trillion yuan ($2.3 trillion) healthcare industry by 2030. A blueprint laid out in 2016 called “Healthy China 2030” vowed to improve public health emergency preparedness and response capabilities to match those of developed countries. It also set targets including increasing the average life expectancy to 79 years in 2030, lowering infant and maternal mortality rates, and having at least three physicians and 4.7 nurses per thousand people.

Anxious Patients

But that still seems a distant goal. Beijing resident Stella Duan is a frequent visitor to the city’s leading hospitals and every time she knows what to expect: Hours spent in packed lobbies and crowded waiting rooms with dozens of other anxious patients.

“When I visited a gynecologist at Beijing Shijitan Hospital in September, I waited two hours to see a doctor,” says Duan, 27, who was lucky enough to have an appointment. “There were three to five counters open and lines of 10 or more people at every one.”

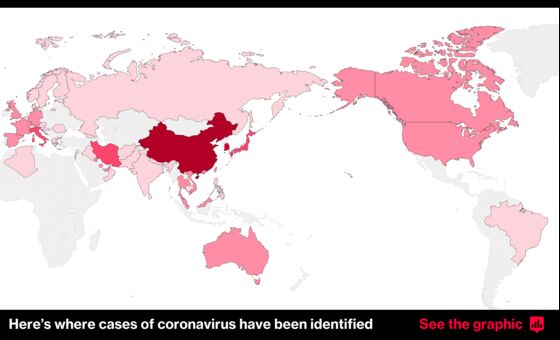

Such an environment, replicated in major hospitals across China, aids the spread of diseases like Covid-19, first identified in China’s central city of Wuhan in December before triggering a global health emergency.

When the coronavirus combined with a governance failure that allowed it to spread virtually unchecked for more than a month, it helped unleash what President Xi Jinping now calls the most difficult outbreak since the Communist Party came to power 70 years ago. He has urged the nation to “strengthen areas of weakness and close the loopholes exposed by the current epidemic.”

“For a time, we thought SARS was a watershed for the healthcare system,” said Huang Yanzhong, who directs the Center for Global Health Studies at Seton Hall University and is a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations. “It did result in big change. Then this coronavirus showed us the emergency response system didn’t function as expected.”

Making the existing system work is one thing, but China also still needs an upgrade requiring more investment in a weak primary care system of local clinics and small community hospitals. That effort has so far failed to gain significant traction, despite hundreds of billions of yuan in investment in primary care facilities between 2009 and 2018.

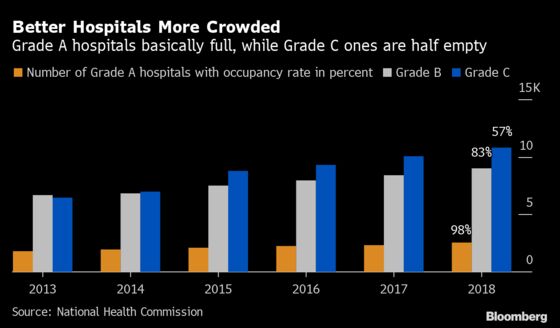

A key reason is the dominance of big hospitals in China’s healthcare system, which enables them to attract the nation’s best doctors and specialists, leaving smaller hospitals and clinics underutilized.

“We saw during the coronavirus outbreak that everyone was going to the big hospitals,” said Chen Xi, an assistant professor of Global Health Policy and Economics at the Yale School of Public Health. “They are having a high risk of cross infection, but they still wanted to go because they do not trust primary care.”

The public healthcare system is “insufficient, irrational and imbalanced,” said former Chongqing mayor Huang Qifan in February.

Fiscal subsidies to hospitals tripled to 270 billion yuan in 2018 from 2010. But overall expenditure on healthcare amounted to only 4.98% of gross domestic product in 2016, a level on a par with Mozambique and Myanmar, according to World Bank data. France, by comparison, spent 11.5%.

China thought it had fixed the emergency response system after SARS. It issued new regulations on preparing and responding to public health hazards in 2003 and a new emergency response law in 2007.

Better Prepared

It built the world’s largest internet-based reporting system for infectious diseases with the goal of quickly identifying and controlling their spread at home and abroad. The system was better than exists in most countries, including the U.S., says William Hsiao, a professor at the Harvard Global Health Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“China is better prepared than ever for epidemics, which may be much worse than SARS in terms of speed of spread and fatality rate,” wrote authors led by Cao Wuchun of the Department of Disease Epidemiology at the Institute of Microbiology and Epidimiology in Beijing in September last year.

Initial praise for China’s response to the outbreak in late January, when it swiftly put Wuhan and much of Hubei province in quarantine, quickly gave way to criticism when more evidence of a cover up emerged. Eight doctors in the city had spoken up about a mysterious new pathogen weeks before.

The eight were called rumor mongers and silenced by local police. One of them, Li Wenliang, would later die after being infected by the virus, causing a social media backlash against the government. People blamed local officials for slowing the response to the virus, and losing a precious opportunity to contain it. The Supreme Court later criticized the police action and several top Wuhan officials were removed from office.

Just how China will respond to its healthcare system challenge remains to be seen. So far the standing committee of the National People’s Congress, the legislature, has only confirmed that improving the public health emergency management system and the Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control Law are on its agenda this year.

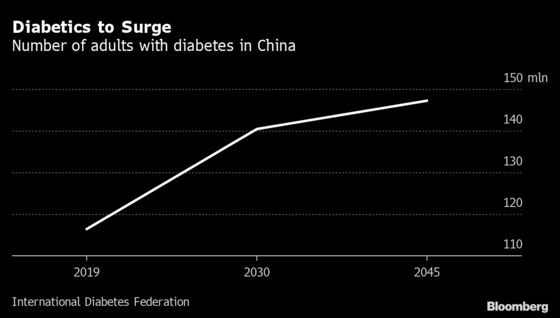

The task of upgrading the healthcare system will be complicated by slowing economic growth and an explosion of people aged over 65 by the end of the decade to 247 million -- more than the population of Brazil. At current pace, China must prepare to handle at least 140 million diabetics by 2030.

One tail wind will be a rising population of wealthier middle class people -- expected to add 370 million by 2030 -- with more money to spend on higher-quality healthcare. Should China get it right, providing higher-quality care at reasonable prices across the system, expenditure on healthcare may surge to 12% of GDP within 15 years, says Harvard’s Hsiao.

China’s secretive Communist Party leaders will also need to find a way to be more “nuanced about transparency,” says Hsiao. For diseases like Covid-19 there’s no alternative to that, he says.

To contact Bloomberg News staff for this story: Kevin Hamlin in Beijing at khamlin@bloomberg.net;Lin Zhu in Beijing at lzhu243@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeffrey Black at jblack25@bloomberg.net, Kevin Hamlin

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg