Coronavirus Sets Up Short-Term Pain, Long-Term Gain

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- What might throw the U.S. economic expansion off course?

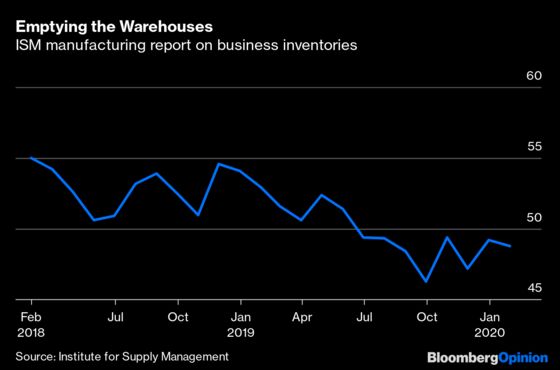

One possibility has to be inventory shortages, at least in the first half of 2020. Stockpiles already had already been reduced in 2019 by businesses wary about the trade wars; they now face the possibility that they will be unable to replenish them for the foreseeable future because of Chinese factory shutdowns related to the coronavirus outbreak. This may mean higher prices -- inflation already is ticking up in China -- and reduced output in the short term, but also may lead to a surge in output later in the year when companies have both the means and the will to restock.

Inventory reductions in the last three quarters of 2019 were the biggest culprit in a disappointing year for U.S. business investment. Between the second and fourth quarter of 2019, gross private domestic investment subtracted an average of 0.8% of gross domestic product per quarter. Almost all of that can be traced to a reduction in inventories. This was the right decision for businesses to make as the trade war was accelerating and the scale of the economic fallout seemed to be mounting. Better to halt expansion plans, sell the products already in stock and hold a little extra cash until the dust settles.

As 2020 began, it looked as if the worst was behind us, with manufacturing and global trade poised to rise. This was apparent both in the fourth-quarter stock-market rally and in manufacturing surveys, such as last week's ISM Manufacturing report, which showed U.S. manufacturing increasing for the first time in six months in January. With the job market and consumption remaining robust, low interest rates and a pledge from the Federal Reserve not to increase them unless inflation flared up, the sensible thing to do for businesses would be to rebuild inventories.

But the coronavirus outbreak in China has thrown a wrench into those plans. First, it has led to a collapse in Chinese demand: Entire cities are quarantined, sending oil and commodities prices tumbling amid a decline in output. For multinational corporations, any time there's concern about Chinese growth, let alone an exogenous shock like this, there's a natural temptation to be cautious. Second, for companies that serve large numbers of customers in the U.S. and Europe, there's concern about the impact on global supply chains. Of course, just because Chinese factories are shut doesn't mean Americans won't still be lining up to buy new AirPods.

Until disruptions to the Chinese economy subside, companies will confront a variety of challenges. For those involved in producing raw materials for manufacturers, it means bracing for at least a short-term recession. OPEC has considered holding an emergency meeting to reduce crude output as Chinese demand for oil plummets. Shares of steel producers such as United States Steel and Nucor have slumped in sympathy with coronavirus fears.

But companies that sell to U.S. consumers have a different set of challenges as consumer confidence soars. Robust job growth, low unemployment, solid real wage gains, low interest rates and falling gasoline prices give consumers even more buying power.

All of this may end up scrambling economic and earnings data for a couple of quarters. There tends to be an inverse relationship between inventories and productivity growth, as selling down inventories without replenishing them makes companies look more productive. To the extent there's a further drawdown in inventories, this may boost productivity growth in the early part of the year, only to give it back later in the year as inventories are restocked. The same goes for profits and cash flow.

The good news for workers and policy makers is that the inevitable rebuilding of inventories later in the year should provide a steady tailwind for the labor market and economic growth. That also would provide a potential boost to President Donald Trump's re-election fortunes as Election Day approaches.

If coronavirus spreads outside of China, that might deal a more serious blow to growth prospects. But if the disruption remains mostly confined to China, its factories eventually will come back online and the conditions will be ripe for a resurgence in both inventory and broader economic growth.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Conor Sen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is a portfolio manager for New River Investments in Atlanta and has been a contributor to the Atlantic and Business Insider.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.