Christine Lagarde’s $810 Billion Coronavirus U-Turn Came in Just Four Weeks

“Lagarde’s turnaround has been quite spectacular,” said Peter Praet, the ECB’s former chief economist.

(Bloomberg) -- Christine Lagarde was barely four months into the European Central Bank presidency when she sat down at her dining room table, two iPads and two phones at hand, and prepared to tell her colleagues it was time to unleash massive stimulus or face an existential crisis.

It was 7:30 p.m. on Wednesday, March 18. Lagarde was in her Frankfurt apartment, and on the line were the rest of the 25-member Governing Council. The goal was to agree on measures to stem the financial and economic meltdown caused by the coronavirus.

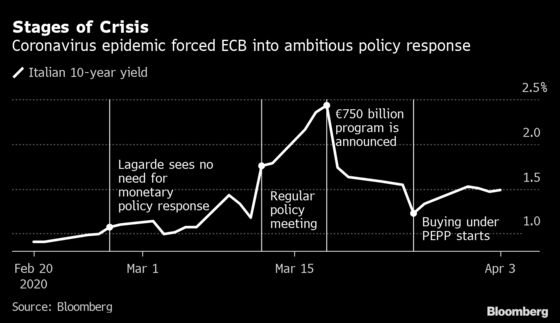

Government lockdowns to contain the disease were causing the deepest recession in decades, stock markets were collapsing, and — reminiscent of the euro zone’s debt crisis less than a decade earlier — bond yields were spiraling in Italy, the European epicenter of the outbreak.

Lagarde had a 750 billion-euro ($810 billion) bond-buying proposal that staff had crafted over a frantic 48 hours right up to Wednesday lunchtime, but there was no guarantee it would pass. Its name: the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program.

That meeting was the crunch point of an extraordinary four weeks, when a public-health alert that initially threatened a temporary hit to growth turned into a full-blown economic crisis. The 64-year-old Lagarde was forced to play catch-up after a slow start and a big mistake along the way. With governments dragging their feet over a joint fiscal response, she ultimately took a “no limits” approach echoing her turmoil-fighting predecessor, Mario Draghi.

“Lagarde’s turnaround has been quite spectacular,” said Peter Praet, the ECB’s former chief economist. “She made a U-turn and delivered something so bold I never thought we could have done so quickly at the ECB.”

Here’s how she got there, according to multiple officials familiar with events behind the scenes, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

The ECB’s view at the end of February was that the virus would cause an economic shock, but a temporary one with a fast, so-called V-shaped recovery. It expected governments to be the first line of defense with fiscal support.

On Feb. 27, a Thursday, Lagarde was in London for a speech on climate change. While there, she told the Financial Times that there was no obvious need to respond with stimulus.

Those comments landed in policy makers’ inboxes with a note from the president, inviting them to have a read. Vice President Luis De Guindos, in Seville, warned against “unjustified alarm.”

Her global counterparts were more energized. The very next day, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell signaled he was prepared to cut interest rates. On Monday, the OECD slashed its global growth forecast, and the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England said they’d act if needed. The International Monetary Fund, which Lagarde led before the ECB, said it stood ready to help countries, and Group of Seven finance chiefs arranged a call to discuss the matter.

It was a stunning change of tone. But there was still no message from the ECB. A statement by Lagarde was actually in the works, though it wasn’t published until well after 10 p.m.

When that came, it was nuanced. The president promised “appropriate and targeted measures, as necessary and commensurate with the underlying risks.” There was no hint of large-scale action before or at the next policy meeting on March 12.

Even after the Fed cut interest rates by 50 basis points in an unscheduled announcement the next day, the ECB didn’t show urgency. The Governing Council was on a conference call about business continuity at the time, and no one mentioned it.

By the following Monday though, ECB staff — all working from home in a test — started to fear they had radically underestimated the risks. European and U.S. stocks slid more than 7%. One person described the mood as terrified and frantic, with phones ringing relentlessly.

It was then that work started on a plan to boost the ECB’s quantitative-easing program by 60 billion euros — later doubled — and economic projections were amended to reflect two scenarios of how the crisis could evolve.

On Wednesday, March 11 — the same day the World Health Organization labeled the outbreak a pandemic — most policy makers arrived in Frankfurt on the eve of their formal meeting, though at least six chose to dial in by teleconference.

Over the next 24 hours they agreed to a lengthy list of measures, including 120 billion euros of bond purchases and generous funding for banks lending to virus-hit companies. The key interest rate was kept on hold at minus 0.5%.

In her press conference, Lagarde insisted that “the response should be fiscal, first and foremost.” Investors were largely content — until just over half an hour into the briefing, when she said the ECB was “not here to close spreads.”

That was a line Isabel Schnabel, a German economics professor who joined the board in January, had used during the council meeting. While strictly true in view of the ECB’s inflation mandate, it was terrifying for any investor familiar with the 2012 debt crisis.

Back then, Draghi had pledged to do “whatever it takes” to stop borrowing costs in stressed Mediterranean economies surging far above safer options such as Germany — a gap known as “the spread.” If Lagarde wasn’t making the same promise, another debt crisis was possible. Italian bond yields immediately soared.

Policy makers considered it a simple slipup, and Lagarde tried to reverse the remarks immediately in an interview with CNBC. But with Lagarde, Schnabel and Guindos — half the Executive Board — all in their first-ever central banking job, the impression was left of a leadership team lacking experience. European stocks plunged more than 11%.

Officials were soon racing to limit the damage. Philip Lane, the ECB’s Harvard-educated chief economist, published a blog signaling that they had no reservations about directing purchases toward countries in distress. Nine other Governing Council members also spoke out in Lagarde’s defense.

When she told colleagues on an early-evening conference call that the market reaction was unfortunate, several understood it as an apology, though it’s not clear she intended that.

In any case, politicians were less understanding. French President Emmanuel Macron said the ECB hadn’t done enough, and Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte said the central bank should be “not hindering but facilitating.”

Those swipes were the latest signal that Lagarde shouldn’t rely on government help to quell the crisis. Every time she had asked politicians for budget support, her calls went unheeded.

During the G-7 discussion on March 3, backed by outgoing BOE Governor Mark Carney and French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire, she fiercely insisted on fiscal aid, but officials agreed only to say they stood ready to act if needed. One week later, when she told European Union leaders that the region risked a crisis reminiscent of 2008 if they didn’t deliver coordinated action, that call also ended inconclusively.

In a discussion with leaders on March 17, Lagarde warned the euro-zone economy could shrink by 5% if the lockdown lasts for three months. While governments were starting to unveil individual stimulus packages by then, it was already clear the ECB would have to act again.

“The ECB has to do what it has to do, full stop, even if governments aren’t yet stepping in,” Jean-Claude Trichet, the institution’s president during the 2008 crisis, said later.

The weekend of March 14-15 was a game changer. Multiple countries including Lagarde’s homeland of France closed businesses and restricted travel. Then during her Sunday evening, the Fed cut rates to almost zero and said it would offer dollars to counterparts — including the ECB.

In Frankfurt, just as the institution itself was largely switching to remote operations, “collective realization” struck, according to officials.

With physical meetings out of the question, Lagarde was on the phone almost constantly as she sought to streamline decision making and gauged the extent of policy makers’ willingness to act. Many said they’d guessed the March 12 package wouldn’t be the final word.

“There was a sense that maybe we should keep some weapons for the future,” according to Bank of Greece Governor Yannis Stournaras. “What we didn't know was that the future would arrive so quickly.”

Economists were tasked with finding solutions. There were longstanding concerns about cutting interest rates further below zero, so Lagarde and colleagues — including Lane, her counsellor Roland Straub, and Massimo Rostagno, director general for monetary policy — told them to craft as large and rational an asset-purchase program as possible. The principle? Go big or go home.

By Monday’s close, European stocks were down 34% from their peak. Over the next two days, banks borrowed 109 billion euros in an interim financing program and $112 billion from the ECB’s swap line with the Fed, showing their liquidity worries. Finnish Governor Olli Rehn warned the situation was “much more critical than a week ago.”

The virus impact even reached Lagarde herself. She self-isolated after coming into contact with someone suspected of having the disease.

On Wednesday morning, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis spoke to Lagarde to ask that any new bond purchases include his country, whose sub-investment grade debt was excluded from existing programs.

Around lunchtime, a proposal started circulating that included the 750 billion-euro target, though it wasn’t clear if that would include the 120 billion euros already announced. ECB staff started warning governors to prepare for an emergency call that evening.

Just after 8 p.m. France’s Le Maire said the ECB should use all its instruments “quickly and massively.” By then, the meeting was under way.

The session itself was relatively calm. Stournaras spoke first, reiterating the call to involve Greek debt, and no-one objected. There were reservations about the size of the program, but everyone agreed the ECB needed to act.

At around 10 p.m., Lagarde had her backing. At 12 minutes to midnight, the program was announced, and she made a statement saying there were “no limits” to what the ECB would do. Investors saw it as her version of Draghi’s “whatever it takes,” and yield spreads started dropping the next day.

The real coup came a week later, in another late-night release: the decision’s legal text revealed the ECB had lifted caps on how much debt of each nation it could buy. That was extraordinary because limits imposed on earlier programs were intended to prevent a breach of EU law on financing of governments.

The next day, March 26, exactly four weeks since Lagarde had said there was no need for a monetary response to the coronavirus, the new purchases started.

“She took leadership, and I would give the credit to the president that this institution has continued to work,” said Praet. “It slipped a little, but the lesson has been learned.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.