Companies Flee Argentina, and Coronavirus Is Just One Reason

After a third straight year of recession, foreign companies, from airlines to automakers in Argentina, are pulling up stakes.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Argentina faces a mounting exodus of multinationals that have concluded that doing business in Latin America’s third-largest economy is just too complicated and unprofitable, even disregarding the coronavirus pandemic.

Powerful labor unions, volatile politics, price and currency controls, and other forms of state interventionism have long been features of doing business in the crisis-prone South American country. Now, faced with a third straight year of recession and a new antibusiness government, some foreign companies, from airlines to auto parts makers, are pulling up stakes.

Latam Airlines Group SA, which is headquartered in Santiago, said it was ceasing domestic flights in Argentina after 15 years in the country. In a letter to the Labor Ministry, a copy of which was obtained by Bloomberg, the airline included a long list of grievances that it said made costs 41% higher, and crew productivity 30% lower, than in any of the 26 other markets in which it operates. Fractious relations with unions, a weak local currency, and a new “solidarity” tax that applies to airline tickets for destinations outside Argentina were among the irritants. The coronavirus pandemic wasn’t the main reason Latam listed. “Constant conflicts in an operation plagued by strikes caused significant losses,” the company said in the letter.

Warren Buffett-backed car-coating giant Axalta Coating Systems, German paint company BASF, and French auto parts maker Saint-Gobain Sekurit have all announced in recent weeks that they intend to shift production to neighboring Brazil, even though the virus outbreak there has been much worse.

Honda Motor Co. stopped making cars in Argentina in May, though it continues to manufacture motorcycles, according to a local automotive industry chamber. American Airlines Group Inc. ended one of its routes to Argentina and terminated its local rewards program with a bank. And Alsea, which operates fast-food franchises in the region, has temporarily closed 37 Starbucks cafes and permanently shuttered another 8 locations.

Many of the big companies that are staying put are shelving investment projects: Volkswagen AG and Ford Motor Co. canceled plans to manufacture pickup trucks in Argentina, according to the chamber.

While the post-pandemic future is uncertain for most countries, the outlook for Argentina, which placed 139th out of 141 countries in a ranking of economic stability compiled by the World Economic Forum, is among the most precarious. An already challenging operating environment has become even more so since President Alberto Fernández took office in December. His administration has further restricted access to dollars, increased taxes, and banned layoffs. The government’s decision to default on the country’s foreign debt, after negotiations with bondholders stalled, and moves to expropriate one of the nation’s largest soy exporters haven’t endeared him to foreign investors, either.

“Closures or transfer of operations elsewhere have nothing to do with the pandemic,” says Andrés Borenstein, an economist at consulting firm EconViews in Buenos Aires. Argentina “lost credibility after years of recession and default. This government hasn’t shown itself to be very pro-market.”

Argentina was one of the first countries in Latin America to impose lockdown restrictions to slow the spread of the coronavirus. The measures, which are only now being gradually lifted, have exacted a heavy toll on an already weak economy. Economists surveyed by Argentina’s central bank are forecasting a 12% contraction this year, which would be the biggest one-year decline on record.

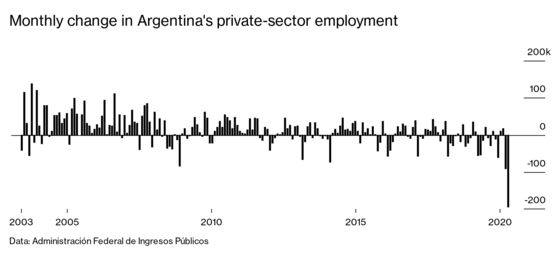

For many capital-starved businesses, the pandemic is the final straw. Government data show that 20,000 private-sector employers have ceased operating this year. Among those still standing, more than 70% of businesses say they can’t sustain operations beyond the next 12 months, according to a poll by a leading business group. “I’d expect more of the private-sector employers and independent businesses to fold over the coming months,” says Jimena Blanco, director of Latin America research at Verisk Maplecroft, a consulting firm.

For sure, Argentina’s economic problems aren’t new. The country has spent a third of its modern history in recession, and growth has been elusive for the past decade. Net foreign direct investment amounted to $5.1 billion in 2019, approximately half the annual totals in each of the two previous years, according to the UN’s Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Negotiations to restructure $65 billion of bonds have made progress, though some of the country’s largest creditors are balking at the terms the government is offering, adding to the crisis atmosphere companies have been navigating since the May 22 debt default, Argentina’s ninth.

Fernández’s administration is trying to help companies on some fronts by picking up the tab for a portion of salaries, suspending social security contributions, and providing billions of pesos in emergency loans. During a July 21 video address to the Council of the Americas, he stressed that his administration is trying to improve the climate for business. What Argentina needs most is investment, production, employment, and development,” he said. “Argentina continues being a country that structurally has a lot of natural wealth.”

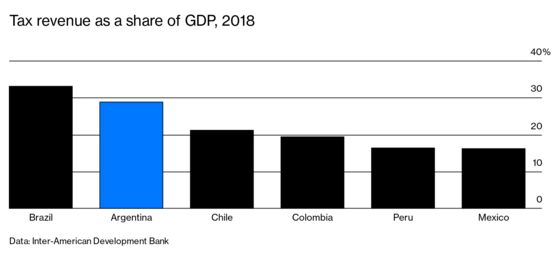

That message isn’t getting through to Patricio Pagani, who started his Black Puma data analytics firm in Buenos Aires two years ago and says he’s already considering moving part of his operation to Uruguay or Chile. Export tariffs hinder business overseas, and domestic taxes are far higher than the average in Latin America. But Pagani says his biggest challenges are capital controls that eat up his profits because they force him to convert payments from clients abroad into pesos at the official exchange rate, now 72 pesos to the dollar, while many of his other costs are linked to the black market exchange rate, presently 140 pesos to the dollar.

“It makes you think, as a business owner, of alternatives to do business somewhere else,” Pagani says. “We’re not competitive at all.”

—With Jorgelina do Rosario

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.